The Truth About Killer Robots

“A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.”

— Isaac Asimov

Photo courtesy of HBO

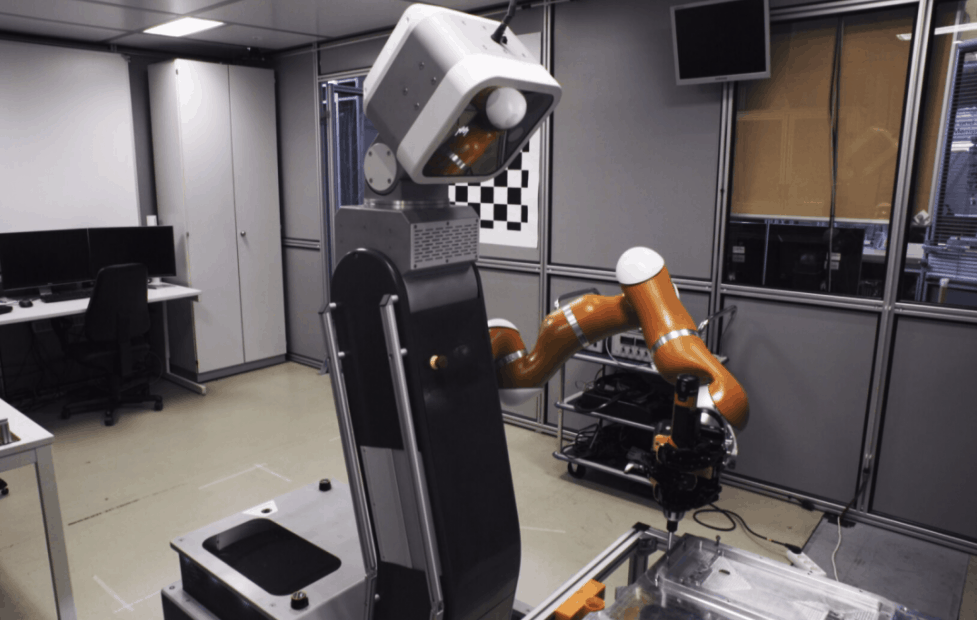

Maxim Pozdorovkin’s high concept documentary, The Truth about Killer Robots should stop you for a second, make you drop the little device in your hand (after you’re done reading this article, ha) and see if you can still relate to people without a robot running interference. How does the word “truth” make you feel? Does it challenge you? Does it mock contemporary media? Max, an expert in propaganda (he has a Ph.D. from Harvard in wait for it … Slavic media, Russian propaganda and early examples of propaganda.) shows us some undeniable truths. In 2015, a Volkswagen factory worker was crushed and killed by a robot in Germany. In 2016, the first fatal accident involving a Tesla on autopilot killed Joshua Brown of Ohio while he was reportedly watching Harry Potter. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become so ubiquitous that we have changed the way we think about problems, consume information, learn and make decisions. Max wants us to be encumbered by the human thought process, not shun technology and consider not what robots can do for us but what they are doing to us.

The film grew from the idea that automation as the cause of literal death seems simplistic—metaphorical death feels more germane. That’s the concept that emerged after Pozdorovkin met with the workers outside of a VW factory where a robot killed a guy. At the beginning of the film a German reporter repeats the adage “dog bites a man, man bites a dog. Where’s the news?” The last thing Max wanted to do was make a film about what robots and automation can do for us, no more compelling than a PSA for the efficiency of machines over humans. Max had to figure out how to make a documentary about structural economics that would be stylized as science fiction and true crime.

Chatting with Maxim Pozdorovkin makes me want to read more, pay attention to everything and consume media with intention—not only documentaries but all forms including my treasured iPhone. If my conversation with Max was typical, I have no idea how he gets people to leave him alone. The following is excerpted from our conversation about his thoughts about The Truth about Killer Robots:

On what he set out to do

Maxim Pozdorovkin: “When I started making this film, I watched almost every news report, TV piece, read a lot of books on the subject and did a really deep dive. And all of them were unsatisfying. All of it was presenting information in a way that wasn’t emotionally engaging. When watching and listening and reading through the material produced about robotics and AI, I saw two major blind spots, which I wanted to correct with this film.”

On blind spot number one

“The first one is that almost all the voices in these pieces were those of CEOs, engineers, programmers — exclusively people who were the direct beneficiaries of the technology. As a consequence, almost all the reporting on the subject centered around the marketing premise of ‘what can robots do for you?’ And while making this film, I realized that I’m only interested in what robots do TO us and the ways that they transform us. Rather than think about AI as this distant threat, I wanted to look at AI as a continuation of automation. To see it as a historical process that transforms society in multiple ways, but as a continuum.”

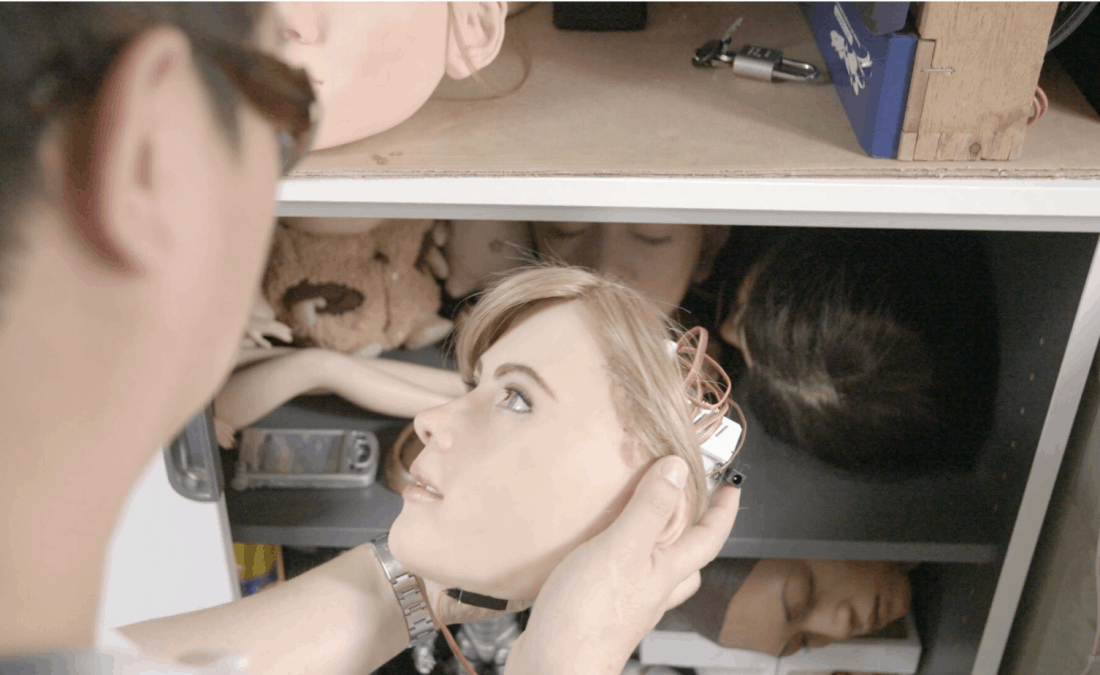

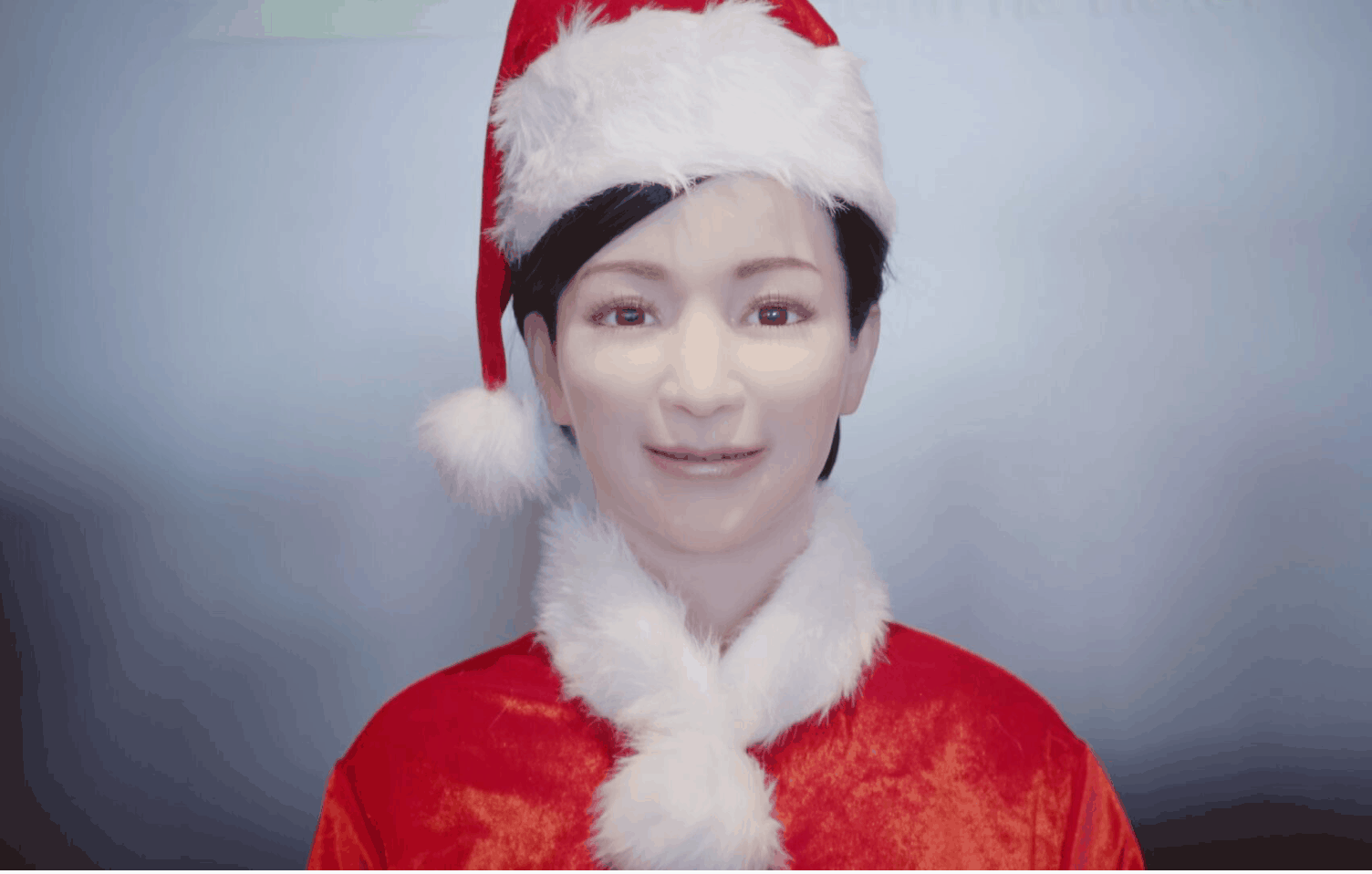

Roboticist Hiroshi Ishiguro and his Geminoid robot. Photo courtesy of HBO

On blind spot number two

“The other major blind spot in the reporting was thinking about displacement only in quantitative terms. For example, this many truck drivers will be replaced. The numbers are important but miss the point that a lot of the true existential change comes from the fact that so much of human dignity has historically been tied up with labor. We are being stripped of skills that were essential to human dignity. De-skilling is rampant nowadays across the labor market. The loss of human memory or spatial orientation, all these things are quite significant but rarely focused on. So, we tried to get this perspective into the film as much as possible. it’s not about being a Luddite and memorizing pointless data. it’s more about not letting skills disappear without a thought, without reflection. That’s what we’re trying to do in the film.”

On how directing The Truth about Killer Robots changed his behavior

“While working on this film, I changed my behavior. I don’t read off screens much anymore. I mostly read books. Associative reasoning is part of the pleasure of reading a book. I want those associations to be generated internally, in my brain, rather than stimulated externally by hyperlinks and recommendations. The idea of being constantly stimulated in behaviorist ways while you’re doing reading corrupts your intake and prevents you from building the inner architecture to really understand something and to learn something.”

On the questionable limitations of AI

“I think that from the beginning I was inspired a little by the Peter Watkins film The War Game and I wanted a future conditional narration as a device. To me it was also, one thing that I saw in a lot of other films about AI, was this idea of making a film around this question ‘Can a robot direct a movie? Or can AI edit a movie? Or can a robot be a DP?’ Asking these ridiculous questions because those are super high high complexity tasks.”

Photo courtesy of HBO

On the James Earl Jones trap

“At the end of these movies we get this false pat on the back, which documentaries are shameful about doing anyway, of “aren’t we special, aren’t we great,” that’s because usually in all of those a robot can’t do any of those things in any halfway competent way. But the worst thing you could do in our movie would be hiring an imitation of James Earl Jones to add like human gravitas to the narration. The idea was that we should embrace the technology and not fall for this false illusion that all it is, aesthetically you just sort of are free from this because if you look at the economic data, what happens in photography, in film, what happens in all these industries is the exact same kind of hollowing out and move from a healthy bell-shaped curve to the to the star system distribution.

“That sort of artist and filmmaker, especially successful ones that have films on HBO and Netflix, they often perpetrate this idea of the artist somehow being immune from these processes. In this film I really wanted to upend that and show that we can use a robot voice over. This film was the first documentary I’ve ever seen narrated by a robot because it was cheaper, and it was more flexible.Using a robot voice to narrate the film allowed us to rewrite the voice over until the very end and work with pacing the pronunciation—this would take many hours and thousands of dollars working with an actor in a studio. Most importantly, I wanted to grapple with the ways that automation is impacting creative endeavors such as filmmaking. We didn’t want to perpetuate the myth that artists are somehow immune from automation.

“Also, the way that we use drone technology in the film is using drones inside factories and in places that show you how it opens up the possibility of something where you would have to use a steadycam operator in the past. Here we’re using the cheap technology because the whole point of making something is to have to grapple with it as well.”

The Biggest Blind spot of all and why it was such a surprise

Max wasn’t surprised from anything in the film, the surprise came “from how pervasive—once I noticed it—this blind spot in all the coverage and the reporting on the subject was. The blind spot of what it does to us. The surprise was qualitative versus quantitative. I’ll give you one example. The section with the guy who marries his android girlfriend. I’ve seen hundreds of pieces, articles, reports about sex robots and sex dolls. Every single one, literally, every single one is premised and predicated and built around this idea of whether the sex is any good. As if that’s the most interesting question that you could ask about that. It’s the least interesting question, right? What we want to grapple with why is this something that will be adopted and will be a part of society. Obviously, that has to do with demographic issues and other things and this kind of reality that some people won’t have [a partner].”

Photo courtesy of HBO

Don’t blame China, think globally

“That not only means that it will happen first in China but that the demographic split is uneven in the rest of the world as well. China is just ahead of that because of their one child policy. But this is going to be a factor. The point is when you are thinking about this you should be thinking about it through this lens of broader globalism. The fact that I couldn’t find a single piece of reporting that even touched on that felt absurd to me. That was the biggest surprise.”

On technological myopia

And that’s why I love that kind of observation that the old man makes to the guy that he’s humiliating all women by applying the term [wife]. Or even to give you another example, the thing in Tokyo, at the convention. This is covered all the time. Dozens of pieces and not a single one asks the women who are standing there. They are clearly the most directly threatened by these freaky androids. Not a single reporter bothered to ask them a question. That’s the kind of ‘techy myopia’ that is so rampant.

Running Time: 82 minutes

In English, Mandarin, Japanese and German with English subtitles

Directed by Maxim Pozdorovkin

Now showing on HBO, HBO On Demand, HBO NOW, HBO GO and partners’ streaming platforms.