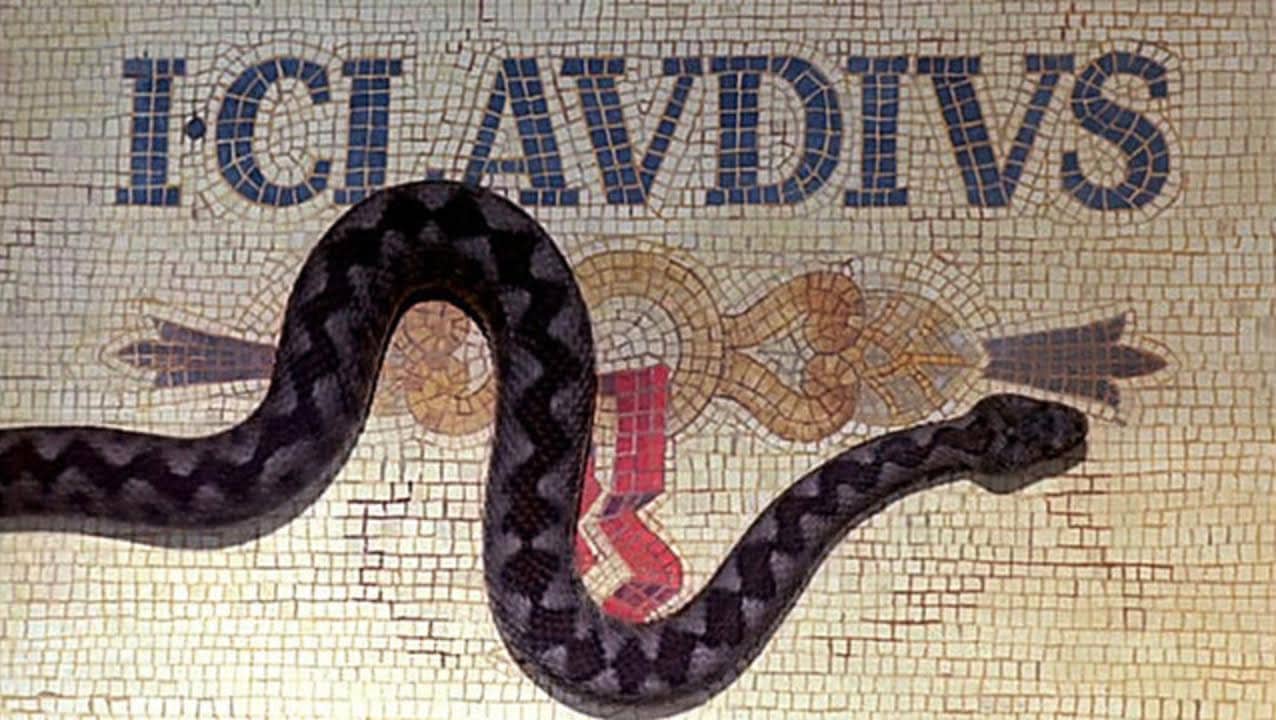

I, Claudius

Long Before the Starks & Lannisters Ruled, I, Claudius Put the Family Saga on the Map

I, Claudius is a 1976 BBC Television adaptation of Robert Graves’s I, Claudius and Claudius the God. Written by Jack Pulman. Directed by Herbert Wise. Starring Derek Jacobi, Siân Phillips, Brian Blessed, George Baker, Margaret Tyzack, and John Hurt.

SERIES INTRO

I tried to develop a story, even before Roots, about four Indian generations. I couldn’t get it on. I tried to develop one about four police generations in a family. I couldn’t get that on. I tried to develop one about an automobile family — four generations in an automobile family. But somehow, I guess the timing was right, and when Roots came along, I said, “What a great idea. Following a black family from Africa, through all the turmoil of its life, until today.” Although, I never really felt myself that Roots was a black story. It was a family story about a black family.

– Roots TV producer, David L. Wolper

I couldn’t write it, until I thought of the mafia.

– I, Claudius screenwriter, Jack Pulman

The theme of family made 1977 a momentous year for the television miniseries — never to be eclipsed, even 40 years later, with TV having ceded many of its viewers to mobile devices. In January of ’77, the long-form TV adaptation of Alex Haley’s Roots became an American cultural phenomenon. During eight nights of primetime network broadcasts, an unprecedented number of estimated viewers (100 million watching the final episode) tuned in for a saga that spanned 120 years and several generations of one family — from 18th Century West Africa tribal village, to a slave ship plying “the middle passage”, to mid-Atlantic American plantations, to a Reconstruction sharecropper farm, to the start of a wagon trail westward.

The crucial early episodes of this immensely important series centered on 18 year-old LeVar Burton as enslaved Mandinka warrior Kunta Kinte, then transitioned to John Amos playing the older version — both, memorably conveying Kinte’s physical and psychological fight to retain the memories and identity of his African upbringing, while forced to live in American bondage under the slave name of Toby. Along the way, he finds a new father figure named Fiddler. He marries fellow slave Bell, and has a daughter named Kizzy, whose son George continues the family line through his son Tom.

The series has the look of TV Westerns of the era, but the true-to-history racist dialogue of these excellent scripts and the honest depictions of the everyday brutality experienced by black slaves, elevates the format far above previous network television depictions of 18th and 19th Century American race relations. Specifically, it is both the aggressive and casual racism expressed by characters portrayed by well-known white actors (many playing against the type of good-guy characters they were known for) including Ralph Waite, Chuck Connors, Robert Reed, Lorne Greene, and Lloyd Bridges, that is effective at conveying the fact that many white Americans during that time period viewed black Africans as essentially sub-human. The visceral novelty of portraying that reality is one of many reasons (including a group of skilled directors steering a cast giving emotionally resonant performances) that made Roots THE miniseries against which all others would be measured by U.S. viewers — starting later that same year.

On November 6th 1977, PBS Masterpiece Theatre in the U.S. premiered its weekly broadcast of the British miniseries, I, Claudius, which had debuted in September the previous year to strong viewership on the BBC — the same network that handled a six-episode run of Roots on U.K. TV in April of ’77. However, this generational story of the Roman Empire’s first five emperors was in dark opposition to the inspiring perseverance of Roots. Indeed, the longer this Julio-Claudian family persisted, the worse it got for all those around them. The family focus in I, Claudius included plenty of murder, incest, rape, greed, lies, and conspicuous consumption of every kind. Needless to say, it quickly became must-see viewing. Moreover, its dramatic legacy can still be seen in another high quality literary TV series focusing on bloody family battles: Game of Thrones.

Unlike the popular HBO adaptation of George R.R. Martin’s fantasy novels about the fictional lands of Westeros, I, Claudius sprang from the pages of two books of historical fiction about the Roman Empire (I, Claudius and Claudius the God) by Robert Graves, both published in 1934. The sales prospects of these books were boosted immediately when Graves granted screen rights to producer Alexander Korda, who tried to adapt them into a film starring Charles Laughton in the title role, and directed by Josef von Sternberg. However, it was not to be. After a month of shooting in February and March of 1937, disaster struck when the film’s other bankable star, Merle Oberon (playing Messalina) was involved in a car accident that purportedly sent her head-first through the windscreen. Shooting was halted, and the film was soon scrapped. 28 years later, rush footage of the lost film was screened as part of a 1965 documentary special, The Epic That Never Was, wherein host Dirk Bogarde summarizes what inspired Korda to adapt I, Claudius:

Now, here was a story of murder, lust, and intrigue on the grand scale. A violent struggle for power with ancient Rome as its spectacular setting.

Bogarde was a 16 year-old art student at the time, and recalled witnessing the grand scale of the I, Claudius sets first-hand:

Already, people were talking about the fantastic sets at Denham. Now, I was fortunate enough to go down myself and see them, and they were fantastic. Korda’s brother, Vincent designed the sets. And in the huge new studios of Denham, which had been specially built for Korda, an army of craftsmen were recreating the palaces, the senate house, and the temples of ancient Rome in all her splendor.

11 years later, I, Claudius was given second life on television, thanks to a fortuitous interest by British Broadcasting in television miniseries programs built around historic figures — including earlier successful six-part looks at the reigns of Henry VIII (1970’s The Six Wives of Henry VIII) and Elizabeth I (1971’s Elizabeth R). Like those programs, I, Claudius was filmed entirely on studio sets, and enhanced its theater-style format with impeccable blocking, camerawork, and soundscapes that psychologically expanded the limited Roman world viewers saw, to one that stretched far beyond the edges of their television screens.

The challenge of successfully adapting I, Claudius fell to producer Martin Lisemore, with financing from London Films. In the documentary, I, Claudius: A Television Epic, director Herbert Wise says the miniseries was pitched to him by Lisemore as a “classic serial”, of which the BBC was airing several each year. Jack Pulman had previously worked with Wise, and was recruited to write the series — in part, because Wise knew that Pulman could work plenty of humor into his scripts to help balance out the darker content.

12 episodes of I, Claudius comprise the 1976 U.K. miniseries (the first episode later split in two for the 13-part ’77 PBS run). As the 40th anniversary of its American airing approaches, I look back at each of the 12 proper episodes, find my favorite scenes, and detail a few interesting notes about the miniseries version of the Julio-Claudian family.

Episode 1 – A Touch of Murder

We are introduced to the Julio-Claudians in 24 BC, at a dinner in the royal palace of Augustus, some three years into his reign as Roman emperor. This is the beginning of a crucial historical period of 78 years covered by I, Claudius, which series historical consultant Robert Erskine described as, “When Augustus’ supreme power, originally only intended as temporary, was hardening into an hereditary dynasty of emperors both good and bad… but mainly bad.”

The first shot of the premiere episode is of Derek Jacobi as an elderly Claudius in 54 AD, writing the first lines of a tell-all history of his family and their many misdeeds — paranoid that he will be poisoned by his younger wife (who is also his niece) Agrippinilla and adopted son Nero, before he can complete his brutally-honest biography. This flash-forward dramatic device frames most of the series episodes, as Wise explained in I, Claudius: A Television Epic:

I looked upon it with the writer like looking through a keyhole at the events that were going on in this family. Part of the thing was it was a huge flashback. In so far that Claudius was writing his memoirs, and I kept cutting back to him to remind us that he is actually an old man reviewing his life and the events in his life, and passing some sort of judgment on it.

Jacobi was cast as Claudius soon after a stint with the National Theater, and having previously worked on the TV miniseries Man of Straw directed by Wise and produced by Lisemore. He was not the first choice for the role of Claudius, which itself was originally intended to be split between two actors portraying the younger and older emperor. However, Jacobi’s demonstration of great physical range during his audition happened to coincide with the I, Claudius creative team deciding on one actor to play both young and old, and helped win him the part. Yet, Jacobi did not have the bankable star power desired by series backer London Films, and had to use all his persuasive charms during a fateful supper with the company’s representative to convince them he was worth taking a chance on as the face of the miniseries — a feat that Jacobi recalls as “the best part of my performance in playing Claudius.”

Beyond Claudius, the juiciest role of the series is the long-lived poison-wielding Livia — wife of Augustus, and blood-related to the next four emperors. On his advice to Siân Phillips for playing Livia, Wise summed up the role as “beauty against evil,” specifically noting, “She was very beautiful, and that was a major consideration in the way I saw the part. But allied to this beauty was this terrible… I mean, this evil, evil woman. So you had the contrast of this. And I love anyway the contrast of comedy and horror (which of course goes right through Claudius), because the one bolsters the other.”

Providing the humor to contrast Livia’s horror is Brian Blessed as Augustus, whose smiling jovial demeanor belies the immense power of life and death that he wields. Blessed told Wise that he felt best-suited to play the more-taciturn Tiberius, but the director gave him Augustus, noting that he wanted Rome’s first emperor played as “an authoritative person, and slightly ludicrous, because he was written pompously, and I was looking for an actor who could actually do this.”

The series opener has many quotable moments from Claudius, Livia, Augustus and others. Yet, for my money, it’s an extended exchange between Livia’s sons Drusus and Tiberius midway through that provides the best-executed drama. Indeed, it gives viewers their only real incite into what drives the man who — whether he wants it or not — is fated to become the next emperor.

George Baker’s preparation to play Tiberius in this scene is a remarkable physical achievement. Makeup and a jet-black wig could hide his 42 years of age only so much. To convincingly play the physicality of Tiberius in his 20s, Baker embarked on a strict diet (no alcohol, bread, or potatoes.) and a grueling exercise regimen to transform his physique. The actor (once named by Ian Fleming as his ideal choice for James Bond, before Sean Connery was cast) woke before dawn every day to jog six miles in London’s Hyde Park, bicycle to the North Kensington baths, and swim 12 lengths — all so that he could achieve the goal of trimming his weight down, and muscling his body up to what it was at age 24. That preparation is immediately put to the test, as the scene opens with he and Drusus (played by the decade-younger Ian Ogilvy) throwing a heavy medicine ball back and forth, before breaking into a competitive wrestling match. The camera lingers on the legs of the two men, the calf muscles straining as they each push to achieve victory. It is a mock battle that Tiberius ultimately loses to the younger Drusus. Their back and forth throughout, though, sells their relationship, and accentuates the good dramatic chemistry between Baker and Ogilvy. We believe Drusus is the very rare someone whom Tiberius can respect and love enough to confide in — providing a crucial opportunity for exposition.

Throughout, we see Tiberius either embittered or sulking at his own easy emasculation and manipulation by Livia. Yet, here, despite his wrestling loss, he converses happily with his younger brother — and father to Claudius — telling Drusus he is one of only three people that he has ever cared for. The other two are their dead father, and Tiberius’ ex-wife Vipsania. Once a tough-but-fair, if socially awkward Roman field general, happy to live out his life far away from Rome, commanding legions, relentlessly training them for battle, and sleeping on conquered ground under an open sky, Tiberius has been reduced to a resentful urban errand boy for Augustus, confined to a royal court he detests, and helpless against his mother’s murderous plans for his advancement within it. Moreover, he is becoming consumed by dark twisted urges growing inside his mind, as he tells Drusus:

Tiberius: “I’ll tell you something, Drusus. Sometimes I so hate myself, I can’t bear the thought of me anymore. You don’t know anything about darkness, do you. Inside darkness. Blackness.”

Drusus: “Oh, stop bragging. I could match you black for black.”

Tiberius: (smiling) “Not you. Not you. They say the tree of the Claudians produces two kinds of apples: The sweet and the sour. It was never more true than you and me.”

Drusus: “And what of our mother? Which is she?”

Tiberius: (frowning) “Livia? They say a snake bit her once… and died.”

Tiberius then explains how he was pressured by Livia (with support from others) into divorcing his beloved wife, Vipsania. When Drusus points out that Tiberius could have resisted that pressure, his older brother takes a quiet tone, and answers with a question:

Tiberius: “Do you think the monarchy will survive Augustus?”

Drusus: “No, I don’t. Rome will be a republic again. I promise you that.”

Tiberius: “Then, perhaps I did it all for nothing.”

Tiberius now turns his back to the camera, sinking his head in remorse. The brothers are posed to match the yin-yang of their personalities. We see the face of Drusus, comprehending his brother’s before-unexpressed royal ambition, and the shift of his perpetually positive expression to one of shock.

Drusus: “Is that why you did it? Is that, really? But there are Julia’s sons. They come before you anyway.”

Tiberius says nothing, letting his silence and turned back express his shameful answer, portending the fate in store for Julia’s sons. Drusus comprehends this as well, and acknowledges it grimly.

Drusus: “My poor brother… So ambitious.”

Tiberius: “Our mother makes me so… Oh god, I miss her so… Vipsania… What did they make me do?”

Tiberius sobs, and Drusus comforts him. Tiberius then expresses his worry of Drusus dying by violence or sickness — thus, losing his last “lifeline into the light.” And though they make a mutual pledge to protect one another, neither brother is safe from Livia — whom Drusus angers with his closeness to Augustus, and his suggestions of a return to a Roman republic:

Livia: “Leave him alone. Don’t encourage him to step down from office.”

Drusus: “Now mother, do you really want us to drift into a hereditary monarchy? Become sinks of corruption like the eastern potentates?”

Livia: “Rome will never be a republic again.”

Phillips delivers this last line with a very-rare vulnerable honesty — another example of the knack Drusus has for drawing out the true feelings of two Julio-Claudians who guard their true intentions the closest. Drusus immediately senses the pointlessness of trying to argue with (though not the murderous decision he has triggered within) his mother.

Drusus: “Well, we needn’t quarrel about it. Come, let me kiss you and say goodbye.”

Livia turns away from his attempted kiss and walks away, the camera rolling just ahead of her as Drusus grows ever-smaller in the shot over her shoulder. To combat this distancing, Drusus takes another verbal swipe.

Drusus: “You know, you mustn’t mind if you dislike me.”

Livia stops, and now Drusus approaches, finally regaining perspective stature beside a clearly rattled Livia, who resolutely avoids his gaze.

Drusus: “A mother can’t love all her children.”

He finally plants a kiss on her cheek, and then walks off, leaving viewers with Livia’s silent open-mouthed expression — facial muscles quivering with the weight of her internal decision to somehow kill this stubborn younger son, so that Tiberius can be manipulated toward furthering her own vision of Rome’s imperial future. And indeed, fate appears to intercede soon after when Drusus sustains a freak leg injury, suffers gangrene, and dies (while under the care of Livia’s personal physician) — leaving ambiguous whether Livia has carried out the murderous intent written across her silent face. It will be Drusus’ son, Claudius who finally extracts an answer to that question years later in a future episode of I, Claudius.

Check back Monday for the second part of twelve: Episode 2 – Waiting in the Wings