Life’s a Gasssss for artist Oliver Clegg

Oliver Clegg, photo by Jamie Strachan

The Clegg family home sits on the southwestern corner of England along a peninsula separating the English Channel and Celtic Sea, where sheer cliffs meet sandy bays and bear the brunt of the relentless northern Atlantic. I called Oliver Clegg there, in Cornwall, just after his lunch. Spring was just around the corner, an early Easter soon approaching, hence his family visit. Clegg, who has lived in New York City since 2012, lived previously in London (he was born in Guilford, twenty-seven miles outside the city) and spent three years in Cornwall before settling in the States. Clegg greeted me warmly and then warned me about a poor Internet connection that would inevitably result in a number of dropped calls. While we talked, he closely watched the ocean just a stone’s throw from his home, tentatively planning his next surf, pointing his laptop seaward when sets approached so I could see.

Traditionally trained as an artist and art historian, Clegg has a self-professed reverence for the historical precedent of painting. He benefited from a conventional, albeit classical, education—which is increasingly rare among contemporary artists as most art programs privilege lofty conceptualism over formal facility. And his practice reflects that complexity—not just in medium but also in method, often evident in his adept use of context. It is no surprise that Clegg’s personal make-up echoes that richness.

He explained how, at twenty-six, he decided to wholly devote himself to becoming an artist, aware that the likelihood of doing so would become more unlikely as he got older. “I didn’t want to work in the art world,” he said. “I’d wanted to be an artist.”

His academic career—which could have lead to a path in academia—is indicative of the doubts he had about realistically working as an artist. And since he’s made the commitment to become an artist, he moved across the pond, leaving the comforts of home behind. Shortly after, he and his wife had their daughter. And his practice seems as verdant as it was when he began. There’s just less time now.

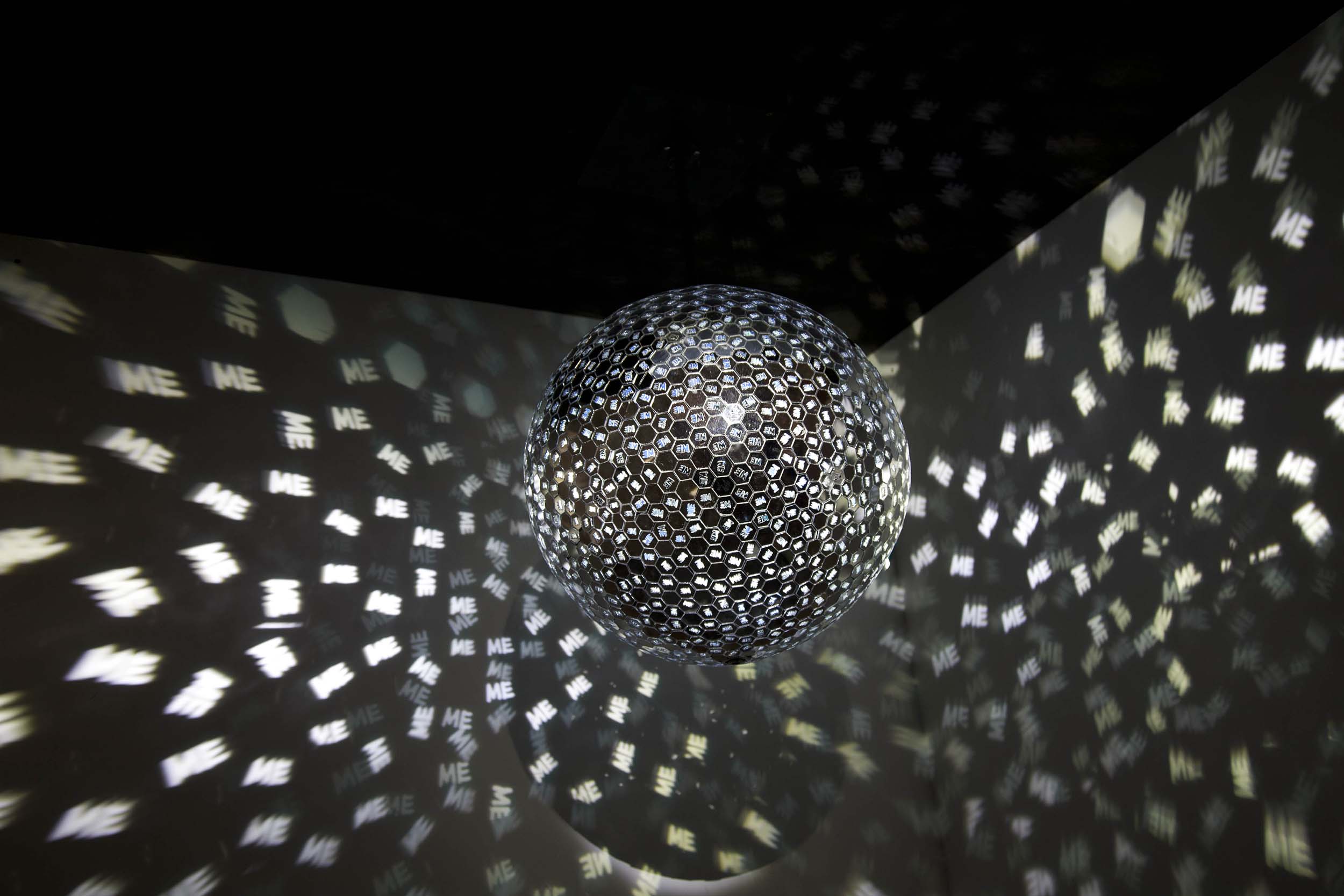

Don’t You? Don’t You?, 2016, Acrylic, steel, electric motor, pin spots, and wood, 30.5 x 18 x 18 in, Courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

When asked about humor or melancholy in his work, he answers both questions alike. What one-person finds painfully melancholic, another almost finds laughable—an idea evident in his work, Don’t You? Don’t You?, which finds a disco ball reflecting the letters M and E in frantic succession, mocking the idea of “me.”

Flippancy turns a shade more serious in Clegg’s work. And that sort of contingent understanding relies on context for Clegg, whether it’s formed geographically, emotionally, or pedagogically. “I feel that humor, because of its complexity and ability to express multiple meanings at the same time, is one way to deliver a profound message in an amusing way,” he said.

This idea for Clegg is made clear through the seventeenth-century Italian term chiaroscuro: the treatment, representation, arrangement, interplay, contrast, and most importantly, the balance of light and shadow. This idea of balance is present with much of his practice.

Clegg’s work emphasizes what is culturally ambiguous in a way that’s acutely sensitive to multiple interpretations of humor, form, and technology. He is soft-spoken and has a light touch, but he’s not wary of acknowledging the immense presence of his personal attitude in his work. His understanding of social ambiguity tends to be the exacting tension that he’s able to drum up—it’s unsettling how intense an emotional investment or complete disparity one can have towards an object.

During our conversation, a few large set waves rolled in, breaking along the point. For Clegg, the appeal of surfing is the challenge of ever-changing conditions. Waves are a series of parts and sections, and when faced with a critical situation, one’s response depends on having encountered a similar situation beforehand. It’s a practiced mental acuity, paired with muscle memory. Clegg explained the feeling as “responding to each individual experience as it comes. I feel that almost every time I paint, I’m re-learning. However, you have your technical prowess in the same way that you know how to paddle. You know how to read waves. But there’s still going to be a challenge each time, which is why surfing never becomes boring, and neither does painting.”

What Came First the Carrot or the Stick?, 2016, Steel, string, and brass pole, 168 x 72 x 48 in, Courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

Initially, surfing was a way for Clegg to cope with his father’s death in 2009. Shortly after, he and his wife moved to Cornwall. He was soon to turn thirty and his daughter’s birth would come two years afterward. Losing his father, turning thirty, and the birth of his daughter, however inextricable, were deeply introspective for Clegg. He told me, “They were very similar experiences in the sense that the loss of someone in your life leads to searching for a stability or calmness, which for me was making work and surfing. In terms of content, there was always a melancholic feeling in my work. Whether it became heightened because of the sense of loss is hard to say. The magnitude of both the loss of my father and birth of my daughter were very similar.”

Spending time in the ocean and in what was then his dining room studio, he cultivated a productive solitude that made clear the “incredible ability of human beings to express emotion. The fact is that if I hadn’t felt emotion when my father passed, I would have been completely distraught, just by the fact that I didn’t feel anything.”

Isolation in a way was a means to allow grief to wash over him, and the turbulent water along the coast was a reprieve from negativity, with the abundance of negative ions in breaking waves. “The reason why surfing is similar to painting is that it’s this meditative mono-practice, where you’re just focused on the thing, catching the wave or making the painting.”

Three years later in 2012, the family moved to New York City, and at that point it seemed as though Clegg’s work took a turn—not necessarily in its arc—but in that it addressed his own personal concerns with the grandiose ideas of America and attempting to make sense of what his position in this foreign place might be. And after so much time in Shire County, the twenty-first century’s waning investment in face-to-face engagement and an insatiable need for instant gratification seemed corrosive. Clegg explained that with his generation, Atari computers and floppy disk games had no communicative component, whereas now one can have undeveloped, shallow relationships with an increasingly larger community of people thanks to the proliferation of social-media outlets but at the cost of isolation and sometimes self-obsession. It’s what he sees as a fraught foundation for friendship. He cynically asked, “Are you validated by the amount of people who like something?” and seemed to imply that this lack of concern for how we interact with one another was like building skyscrapers on hallowed ground.

Until the Cows Come Home, 2014, Installed at the Brooklyn Museum, Courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery; photography by Giles Ashford

Clegg’s respect for long-term engagement, hospitality, and friendship is demonstrated eloquently in his work, Until the Cows Come Home—commissioned for the Brooklyn Museum’s fourth-annual Brooklyn Artists Ball in 2013. This piece set a perimeter of twenty chairs—facing each other—in two bound rings with the exterior ring revolving at varying speed so that any participant may or may not speak to one another at length. The work is bright, with primary red, yellow, and blue implying the more fundamental parts of social interaction or maybe alluding to how we learn to behave. And as the outer ring spins, each person speaks to one-another throughout an entire revolution as though suggesting an alternative to the flippant use of social media. He explained, “Here is a table that satisfies your social media anxieties of needing new images and new information available all the time, but it’s without having anything that plugs in.”

Until the Cows Come Home, 2014, Installed at the Brooklyn Museum, Courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery; photography by Giles Ashford

Over the past ten years, Clegg has titled pieces after chess positions; he built a chess set from the rubble from a now-demolished studio; he’s played chess personally in some of his work. If surfing were like painting, Clegg told me, then chess was undoubtedly like navigating the art world. “There’s strategy in the decision to move from Cornwall to New York, because obviously going from complete isolation to being at the center of things is going to have a profound effect, not only on the context in which people see your work, but also in the way you draw inspiration from your peers.”

He acknowledged the reprieve that trips to Costa Rica and other surf destinations offer from the hustle of New York or the art world. And he explained to me how he enjoyed being able to relinquish control to the extent that at some point he would have no choice but to intuitively respond like one does in their work or on the face of a wave. The disappointment yielded by unmet expectations and the need for control can be as though you’re swimming against a rip current. You’ll eventually tire and it will move you away from shore.

Untitled # 12, 2016, Oil and transparent gesso on canvas, 66 x 66 in, Courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

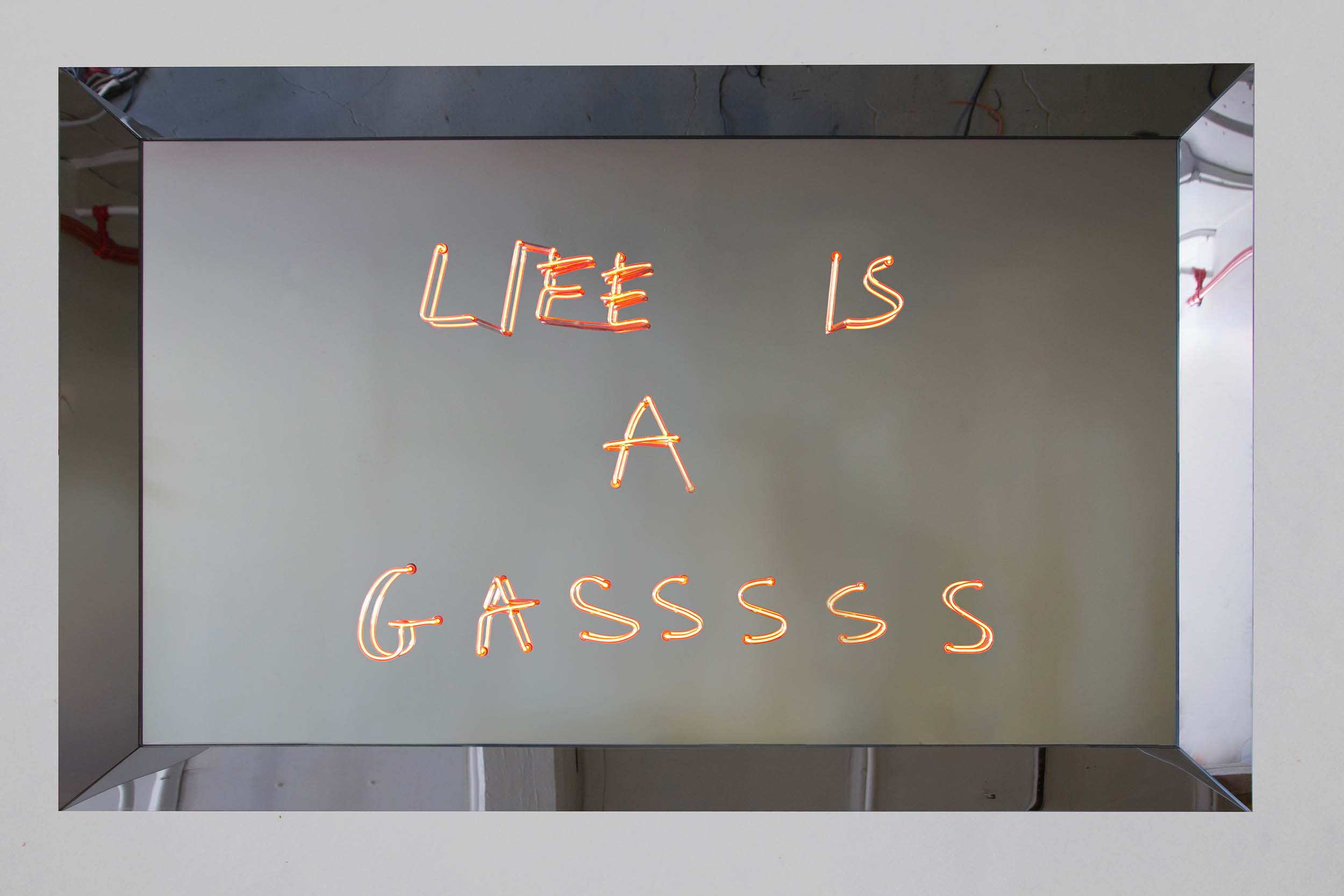

This year, Clegg has just finished the installation of his solo-exhibition, Life is a Gasssss, primarily paintings with a fair portion of sculpture. It brings to mind all of the states Clegg’s practice has gone through over the past decade, in what he has described as, “a pointless yet completely point-full pursuit.” Balance, melancholy, and humor all work together in Clegg’s new body of paintings as they represent the deflated and seemingly forgotten enjoyment of internationally accepted cartoon characters from Kermit to Garfield. These paintings prod the dense layers of cultural information pertaining to these characters, as well as intense personal investment for some. While some see Hello Kitty figurines as indicative of a cutesy stage of youth, others only see it as a response to the trauma following World War II. That’s the liminal place in which his work operates. The multiple meanings and understandings of his work allow the audience to grin a somber grin.

Untitled # 11, 2016, Oil and transparent gesso on canvas, 66 x 66 in, Courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

We finished our conversation speaking about the doldrums of surfing in New York— whether it was the commute, the influx of yuppie surfdom, or the ego wrapped up in it. I couldn’t help but think back on everything we’d discussed as a tic-tac between surfing and the art world, life and death, and more to the point how one can give resolution to such questions simultaneously. Whether it’s humor or melancholy, both are tools that help or hinder us in making an important point; each play a role in how we cope with grief and trauma. Clegg reflected on all of those decisions briefly. “You do these things for the right reasons. Hopefully.”

Life is a Gasssss, 2016, Neon, wood, acrylic, and mirrored glass, 72 x 44.25 x 6 in, Courtesy Erin Cluley Gallery

Oliver Clegg’s solo-exhibition, Life is a Gasssss, runs from April 9th until May 7th at Erin Cluley Gallery, 414 Fabrication St, Dallas, Texas, 75212.