The Hours and Times — Film Review

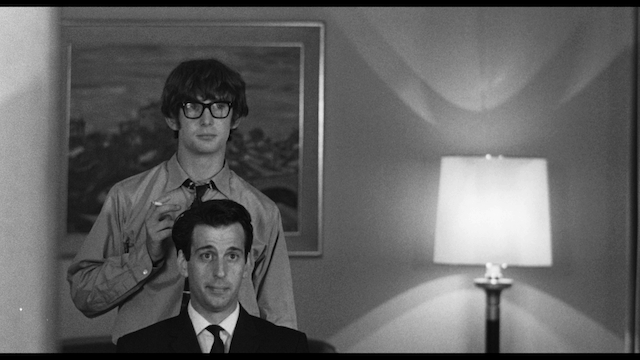

Ian Hart as John Lennon (left) and David Angus as Brian Epstein: Photo Courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratorie

If The Hours and Times seems dated, roll with it. The film is a conversation as imagined by director, Christopher Münch, between John Lennon and Brian Epstein that may or may not be reality based three decades before the film was first released. Restored, remastered and rereleased for Sundance 2019 before rolling out March 1st we time travel in a black and white world from London to Barcelona—an era where time feels like it is on our side (I know, wrong band) and the world is resplendent with sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll. Except it wasn’t. Yet. The film debuted at Sundance in 1992 when Sundance was still a festival for emerging filmmakers and not repeat offenders. Münch deserves a pass though. He resisted the mainstream in favor of remaining an artist. In 1988 the filmmaker wrote the script in two weeks with no intention of making it into a film.

David Angus (front) & Ian Hart (rear) in The Hours and Times. Photo Courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

Awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1993 for his work in film must have tickled the Guggenheim Foundation. They honored his father, Guido Münch, the prize three times albeit for astrophysics. The director continues to make content without regard to Hollywood norms. 1992 was still the time of the AIDS crisis. It preceded, “don’t ask, don’t tell,” which we find abhorrent now, my gay friends at the time, found it a relief. Münch suggests that Epstein who was gay, felt physically attracted to Lennon who at the very least felt emotionally invested in Epstein.

The two men spend four days together in a hotel in Barcelona exploring their friendship, which clearly has to remain platonic to survive. Often referred to as “the fifth Beatle,” Epstein died of a barbiturate and alcohol overdose at the age of 32. Played by the post adolescent looking Ian Hart who is more a Paul McCartney lookalike than a John Lennon Doppleganger and David Angus who conveys Epstein’s ennui over unrequited love, the two men cement the period of the early 1960s. They look like black and white movie characters and not 1980s kids.

David Angus (front) & Ian Hart (rear) in The Hours and Times. Photo Courtesy Oscilloscope Laboratories

The script itself is lean. Banter for the sake of filling sixty minutes of sound never concerns Münch. He reminds us how so much can be said through the visual medium of film. A movie doesn’t need to be loud to resonate. Sometimes a longing look with the camera placed in exactly the right position tells more about what is happening within rather than what spews out. Munch gives his characters room to breathe and trusts his audience to use their imaginations and become part of the process. It’s difficult to remember that Reservoir Dogs and Poison Ivy came out of Sundance the same year.

OSCILLOSCOPE LABORATORIES presents THE HOURS AND TIMES

Written, Produced, and Directed by CHRISTOPHER MUNCH

Starring DAVID ANGUS and IAN HART

Run Time:58minutes

THE QUAD CINEMA