Shaka Zulu

Night-4 Hour-2

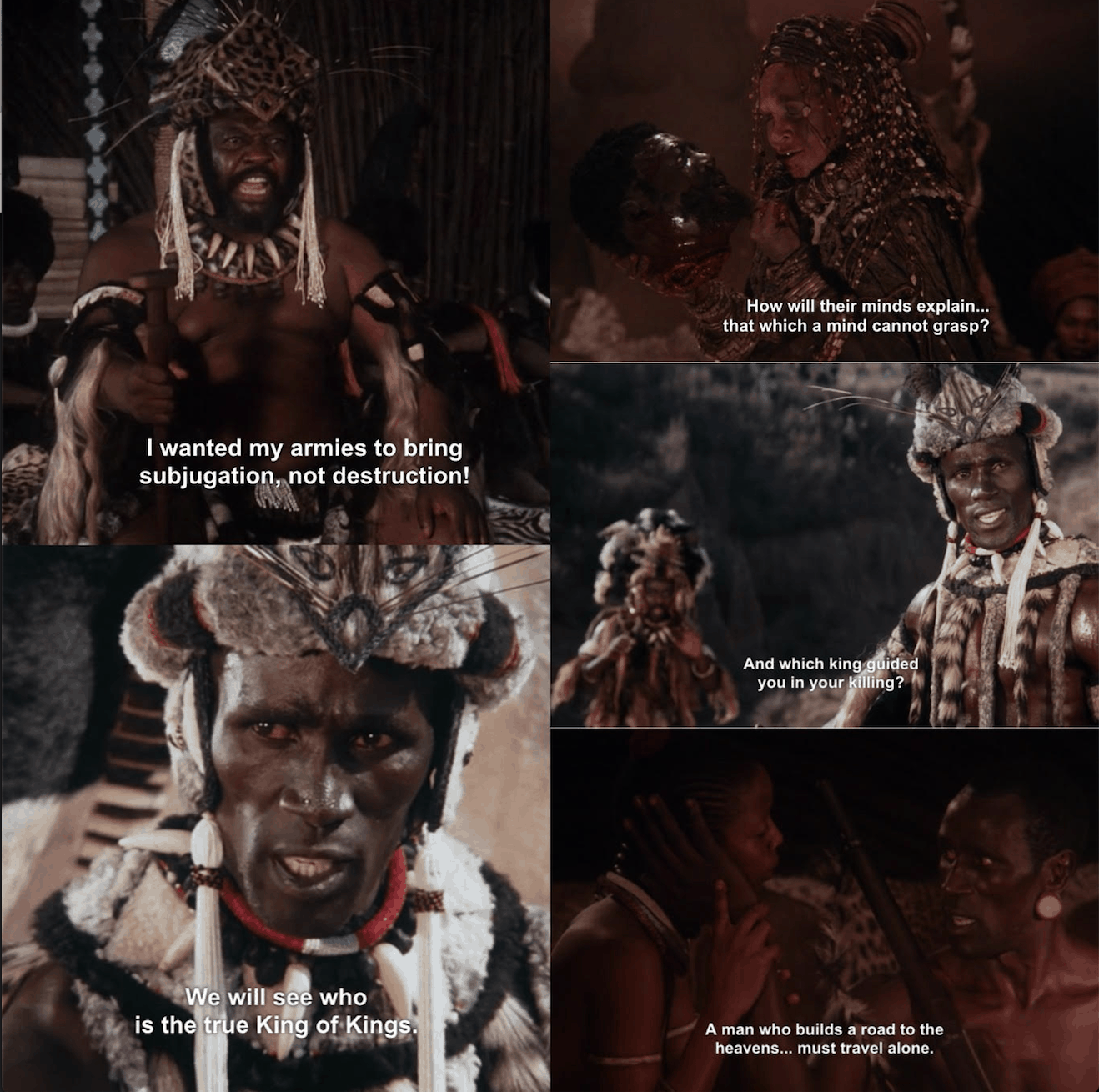

Dingiswayo: “I wanted the name ‘Mthethwa’ to stand for peace! Not total war! I wanted my armies to bring subjugation! Not destruction!”

Shaka: “To subdue another tribe, you must strike it once and for all. Total war! Total subjugation to the paramount king! And total destruction to anyone who raises even a whisper against him. Never leave an enemy behind, or it will rise again to fly at your throat. There is no other way!”

— King Dingiswayo reprimands Shaka, the general of his armies, over the latter’s brutal tactics. From hour eight of Shaka Zulu.

Total war between Shaka and Zwide plays out as a brutal blood feud on night four, with the “life-giving” Swallows forced to prove their powers of death to save themselves… and win victory for the Zulus. Doing visual justice to the censor-provoking story details in this hour is a crucial filmmaking achievement, and goes far (contractual obligations aside) to earning its director the full title of the miniseries, which reads William C. Faure’s Shaka Zulu. Though credit for the high quality story and cinematography go to Joshua Sinclair and Alec Mills, respectively, it is Faure who energetically harnesses those elements — shifting seamlessly throughout the hour from the delicately-handled gore of Dingiswayo’s assassination by supernatural beheading, to the gratuitous body-ravaging rounds of destruction inflicted by Swallow rifles and cannon against Zwide’s spear-wielding Ndwandwe warriors. In all cases, the blood seen on screen (especially lingering shots of Dingiswayo’s headless body) feels earned, thanks to the narrative time invested in the lead-up. Moreover, with Faure credited for Shaka Zulu’s script editing and narration, it was he who shaped Dr. Henry Fynn’s journal voiceovers that provide brief-but-effective flashback introductions, such as this:

Shaka had begun to realize the importance of the diary, and that for him it could represent a form of immortality. And so the king would summon me to his hut, and with apparent relish, relate the violent episodes of his conflict with Zwide, who soon would be our misfortune to confront.

Faure’s succinct transition also echoes longer expository dialogue crafted by miniseries screenwriter Joshua Sinclair — whose earlier lines for Shaka use the king’s self-declared status as Jesus’ heir to explain a diplomatic use for Swallow-gifted “immortality”:

Shaka: “This man Christ had the multitudes in his own hands, yet he was afraid to govern them. Hanging from a tree was easier… Georgie and I mustn’t make that mistake. We must have more courage. Perhaps a nation could be built where the whites and the Zulus would live together in harmony. A council of elders would be formed with the wisest men of each kingdom, and these men must be given eternal youth, so that the heart of the nation would be immortal… Do you think this could be possible?”

Farewell: “Yes, nothing is impossible, if two kingdoms truly wish to live in harmony.”

Fynn: “You’re starting to sound like Gulliver.”

Indeed, like Jonathan Swift’s fictional “giant” who stole an enemy fleet for the Lilliputians in Gulliver’s Travels, the Swallows use their unique advantages (rifles and cannon) to clear the battlefield of Zwide’s Ndwandwe warriors for Shaka’s Zulu forces. They’re so successful that when Zulu general Mgobozi is finally ordered to attack with the main body of warriors, he looks over the Swallow-wrought massacre, and informs his king, “They have made the kill. We march in only as scavengers.” That kill will be finished off with a savage exclamation, as Fynn (on Shaka’s order) ignites the close-range cannon execution of a terrified Zwide.

Yet, as commanding as Henry Cele’s Shaka is on screen, it is the unseen direction of Faure that helps extract the miniseries star’s many-layered performance. You can see its depth in close-up shots of Cele’s eyes, which subtlety widen and narrow across moments of unspoken hatred, suspicion, humor, and bloody triumph. You can also hear it in the tone of Cele’s voice, which effortlessly swings from the deep-pitched intimidation of his warrior king persona, to the softer smiling psychological warfare of conversing with the Sparrows. However, it is the final scene of this hour that sees Shaka show rare emotional vulnerability, after he submits fully to the death-dealing powers of the Sparrows, and the romantic urges of his own heart.

Ever the military innovator, Shaka cannot ignore the advantage of European firearms, and Alec Mills frames a scene that reflects the king’s growing infatuation with modern Swallow technology. As his people celebrate the victory over Zwide outside the royal hut, we observe Shaka inside of it from across his campfire. He sits alone, staring into the crackling flames, a rifle cradled over his shoulder, while his iklwa is set aside nearby. After dismissing Ngomane’s attempt to lure him outside to join the celebration, Shaka is visited by Tu Nokwe’s Zulu maiden, Pampata:

Pampata: “Let me love you, Shaka. Let me help you find love.”

Shaka: “For what purpose, my little one? Perhaps through that love, you will show me how to better rule my people?”

Pampata: “No, your people have nothing to do with it. I merely want to help take away the loneliness.”

Shaka: “A man who builds a road to the heavens must travel alone.”

Still, he gives in, lets Pampata take away his rifle, and they can have sex beside the fire. Rather than the week’s usual thumping outro of Margaret Singana and the Baragwanath Choir’s miniseries theme, “We Are Growing,” night four closes with a soft-toned melody of Stella Khumalo’s “Wemsheli Wami” that evokes the possibility that the long-hate-fueled Shaka may finally have opened his heart to love. Tomorrow night, though, will reveal how he deals with that new emotion in the face of betrayal by the two women he loves most.