Voyage and Craft

On September 11, 1973 Chile’s president, Salvador Allende, was overthrown during a CIA-backed coup d’état, and the government replaced by a military junta. In the following years over 3,000 Chileans would die or go missing under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. The regime’s systemic suppression of political parties and activists also led to the displacement of 20,000 people. Early among the asylum seekers were a young doctor, his wife, and their infant son, Pedro Pascal. “I’m still working on the short version of how I ended up in Red Hook,” says the forty-year-old actor. Over the past few years he hasn’t spent much time in that Brooklyn neighborhood. Pascal’s work on the set locations of HBO’s Game Of Thrones, the director Zhang Yimou’s Great Wall, and most recently Netflix’s Narcos, has taken him everywhere in the world but home. At Large Magazine’s chief editor rang Pascal in Bogotá, Colombia—where he’s filming the second season of Narcos—to talk about DMs, South American history, and to find out what prop cocaine is made of.

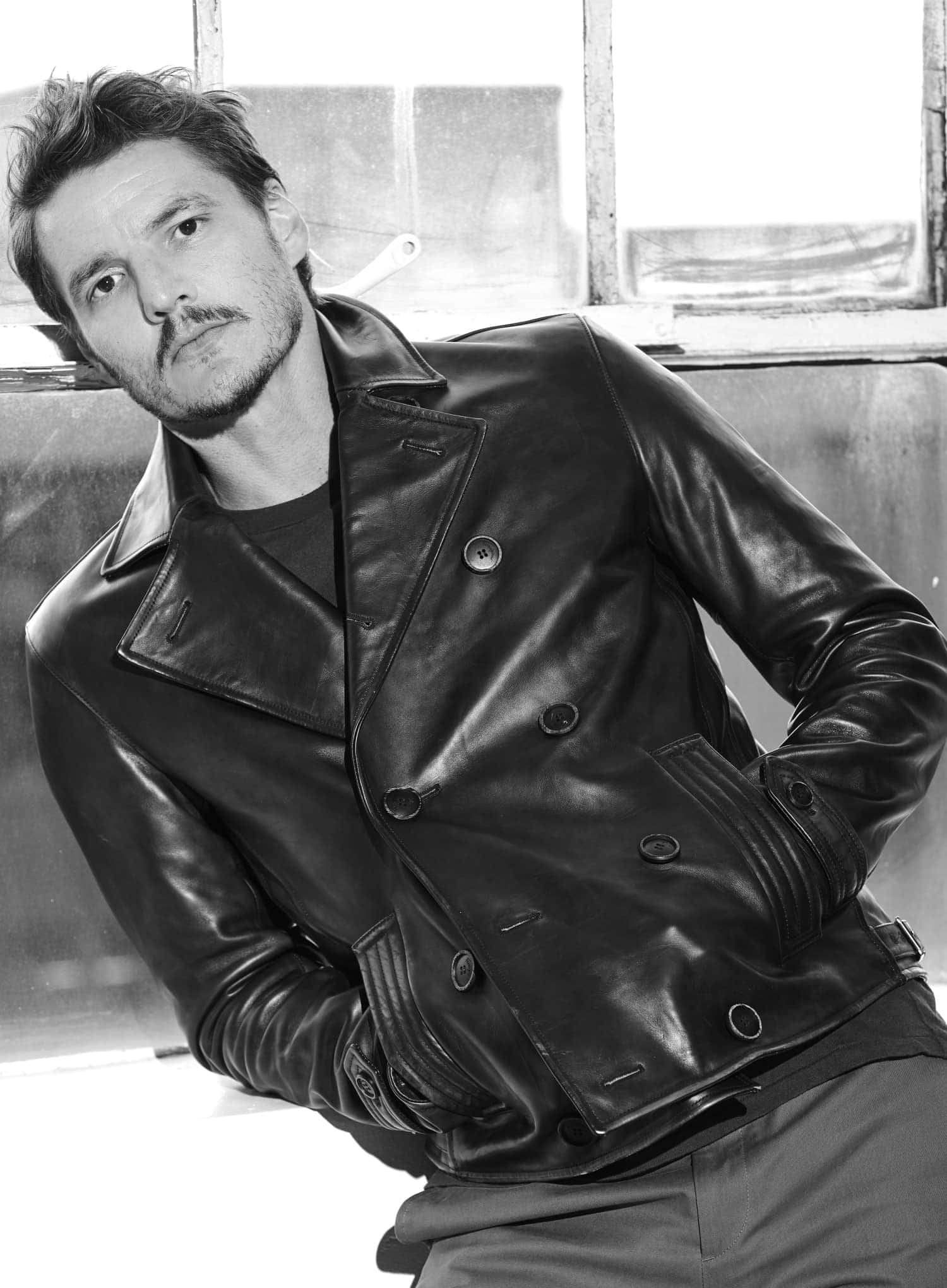

Harrington jacket GRENFELL, T-shirt RAG AND BONE, Pants CANALI

Erik Rasmussen: Where did the idea to be an actor come from?

Pedro Pascal: From the time my dad was a child he was a huge moviegoer. My earliest memories of my family, and my dad primarily, are images from movies we’d seen together. The fantasy started for me at a very young age.

Your parents flee a military dictatorship, work hard to become successful in an adopted country, and you think, “Right, I’ll be an actor.”

The usual story is that the hard working immigrant family says, “You’re going to be a doctor or a lawyer. Or start a business.” My parents were just like, “Whatever gets you out of the house”. At one point I became a good swimmer and my dad was suddenly excited that I’d be an Olympian. They were very untypical. As soon as I got to the age when I could take theatre classes, my parents were happy because it occupied so much of my time.

You weren’t an instant success. What made you stick with acting?

My naiveté: wanting to be an actor and the assuredness that I’d make it got me through the first chapter. I also was very fortunate that I got professional representation early on. I was able to do some auditioning and come close to getting parts. It was at a much smaller scale [than now], but I started working a year out of college. That went on for a while and it kept the dream at arms length rather than letting it die. Then it derailed and I went to wait tables for a couple years.

Why do actors wait tables?

Because it’s a night job and the hours are somewhat flexible. I worked dinners and auditioned during the day.

Jacket and T-shirt VISVIM and Scarf J.LINDBERG

Was New York a different place for you after your role as Oberyn Martell on Game Of Thrones?

By the time the season aired I’d been offered a role in a production of Much Ado About Nothing in Shakespeare In The Park. So my exposure to people’s reactions to Thrones and the part [of Oberyn] was very direct. We’d finish a Much Ado performance and then outside were all these fans from Game Of Thrones. Also, having lived practically my whole adult life in New York, and understanding my routine—going out and getting coffee, getting on the F train and going to work, walking around or whatever—to then see the reaction to Thrones on the subway, people smiling at me, asking for selfies… I really liked it actually.

You make a lot of references to Punk. Your Instagram handle, for instance, is @pascalispunk…

That was a typo. I meant to write Pascal Is A Punk…

…You must get some crazy DMs.

Dude, I get no direct messages on my Instagram. People keep telling me they’re getting private messages: “All these girls want to go out with me.” Or: “Guys are showing me dick pics.” And I’m not getting shit. I’m on the phone with you right now, I just opened up my Instagram, and I got nothing!

You’ve also said that Oberyn Martell is punk.

Oberyn Martell is the total punk rocker of the fourth season. He’s the essence of punk: not abiding by anybody’s rules, but only with the intention of remaining completely soulful on his own terms.

As a viewer, it seems that any time we get a sense that a character is fucked then, well, he’s fucked. There are no storybook-endings or deus ex machina to the rescue. Does that give a sense of reality to a show that’s otherwise fantasy?

Thrones takes the fantasy genre and bends it into very harsh truths. It models itself on true politics and real events in our very ugly human history. I think that’s what makes the show special. There are dragons and there are people wearing crowns, but their frightening medieval morality reflects some of our truths. I think it’s amazing that people dig that.

Where does Martell’s accent come from?

I didn’t want to do a bad British accent. And I knew that the character couldn’t sound American. The first thing that occurred to me was that this guy sounds like my dad. I did an arbitrary Latino accent, not attributed to anyone particularly, but in the “sound” of my own father. I didn’t think about it that much. It was an instinct.

Jacket SALVATORE FERRAGAMO, T-shirt RAG AND BONE, Pants VISVIM

Oberyn Martell is the total punk rocker of the fourth season. He’s the essence of punk.

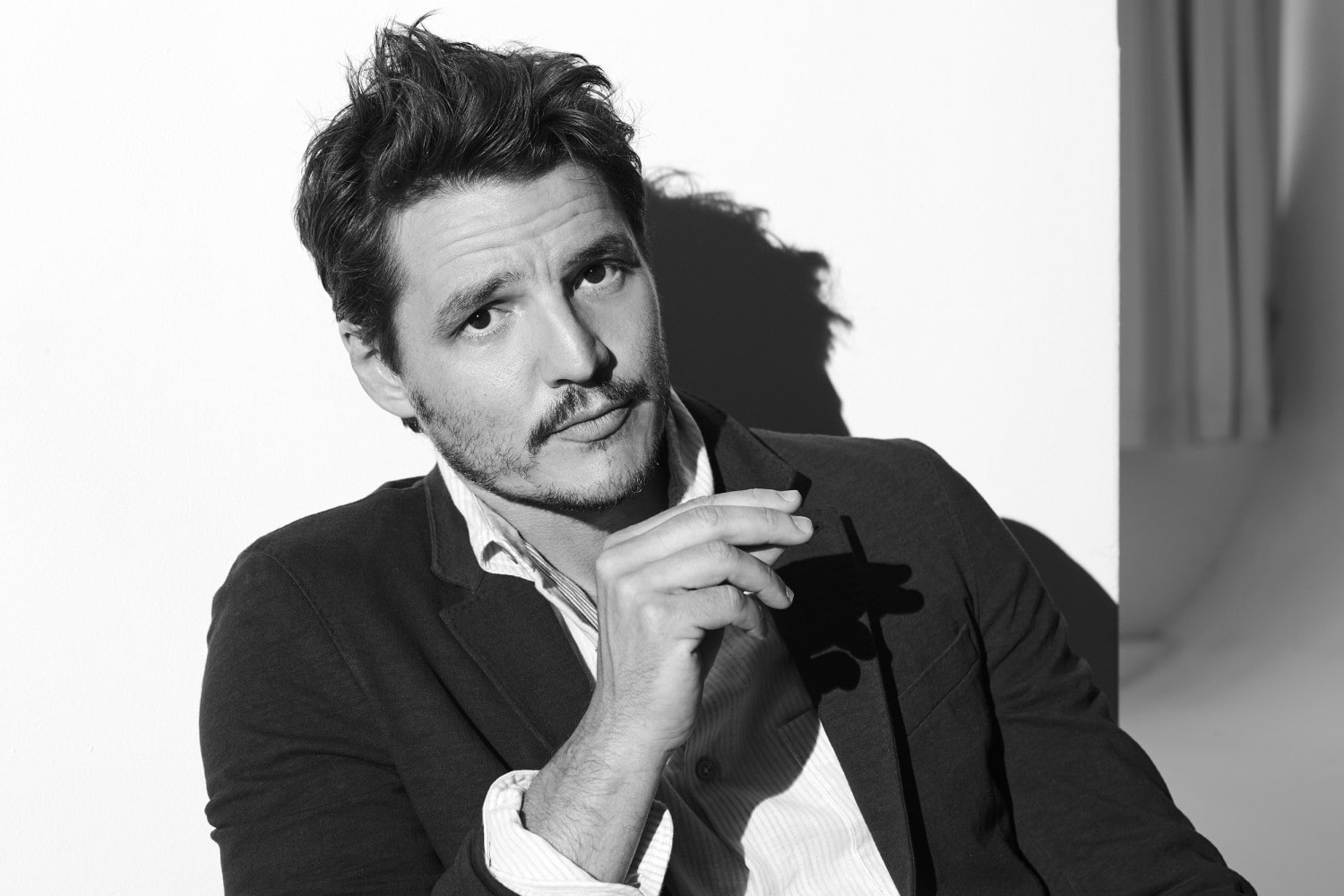

Jacket and shirt RAG AND BONE

There are parallels between the characters Oberyn Martell in Thrones and Javiar Pena in Narcos. They’re both hedonistic, albeit to different extents.

Pena’s primary focus is his work. But similarly to Oberyn, he can’t deny the beauty of another person. He’s a horny guy. Helena [the prostitute in the second episode of Narcos played by Adria Arjona] is undeniably attractive. For Javier to work with a person like that, if she’s game, he has to go for it. What I think is cool about their relationship, however brief, and what I think is cool about Javier Pena, is that he’s on equal standing with this person.

The relationship didn’t work out so well for her.

The most important thing for me concerning Pena is that for him to see things in clear shades of right and wrong won’t get the job done. I find that to be interesting because it sets few limits in terms of what he’s capable of doing—good or bad.

How did you prepare for your role in Narcos?

I went with my fellow actor, Boyd Holbrook, to Virginia and met our counterparts, the real life Steve Murphy and Javier Pena. We hung out with these guys at the DEA headquarters, met the head of the DEA. Then we went over to Quantico, took some classes, got to do simulations. Learned how to use a bunch of different weapons. Quantico is like an amusement park of tactical training.

Are there differences in playing a character based on a living person versus playing a fictitious character?

It’s different in the same way that each job can feel different from the next. I’ve never come up with a way of approaching a role. I figure it out as I go through conversations with directors, through experiences. When I met Javier [Pena] I found that I didn’t need to base my character on his specific characteristics, but I did find that he was almost like a book, a primary source of information and inspiration. He wasn’t looking to make an impression on me as to how I should play him. I found him to be extremely human and friendly. At the same time, you could never really know what he was thinking.

What did you know about Pablo Escobar before doing Narcos?

I knew how he existed in popular culture. I went to Bogotá, Columbia with my family in ‘89. I remember we had to drive around with bodyguards. There was no sit down conversation about Pablo. I got a very thin passing impression about what was going on in Colombia at the time and what reality was like for people on a daily basis. I gathered a few impressions from that.

What is movie cocaine made out of?

I don’t know. My character doesn’t get to snort it. I’ve asked the same question. I’ve always wondered. It’s been described to me as a natural powder with zero effect. And I’m like, well, “What about the dust?” I keep thinking about that powder in Adaptation that they snorted up their nose. That shit was green!

Jacket CANALI, Shirt and tie DIOR HOMME

I’m too embarrassed to share my perspective on what the Colombian drug wars are. But I’ve learned a lot. And the only way I can navigate my way through it is by the intimate experiences of this one character’s story.

One of my favorite scenes in Narcos is when Cockroach takes Pablo Escobar through a tour of the cocaine lab while describing the “product” as all natural and organic.

This is stranger than fiction. You just can’t make this shit up. And the crazy thing is that so much was happening at the time that even with the broad strokes they use in the show there’s way no way to cover everything.

The amazing experience of shooting in Bogotá is that the drug wars weren’t so long ago. People involved in the experiences of the time are still alive—well, if they survived it. There’s a generation whose childhood was shaped around this era. For many of them life is totally normal and yet there are, with anyone you speak to, direct experiences in their lives to do with this time in Colombian history. A woman told me a story the other day: [In the 80s] she was at a restaurant with her family and at the end of the meal their check was already paid in full. They didn’t understand why. Then gradually they realized Pablo Esobar had paid every check in the restaurant. He was sitting in the corner. He held up his drink in a toast to everyone saying, “It’s all on me.” These were people who knew who he was, yet they didn’t know that he was there having dinner among them.

Did Escobar get the level of popular support he did in the belief that he could enact positive change, or were people only loyal to the drug money?

I think something of this size determines itself on many different terms, which ultimately get out of control. On one side, it’s business. On the other side of it there’s the liberation of the people, the social politics of a city, and culture. Which is exactly why there are so many stories that come out of it. Look, [cocaine] became a multibillion-dollar national industry. There are people that honor Escobar as a saint, and others see him as the devil. All of the supporting characters in this, on both sides, have a number of different reasons for getting involved in the war. There are people that can identify themselves as much from the “right” as from the “wrong”. There are the cops and the criminals, but they can all become this grey soup. That’s the way that I see the show in a way.

Can Narcos serve as a warning now against the dangers of mixing “quiet” money with politics?

It’s interesting to do a show like Narcos and to then try and answer questions like this. I’m just an actor. The size of all this is way too much for me, and I’m too embarrassed to share my perspective on what the Colombian drug wars are. But I’ve learned a lot. And the only way I can navigate my way through it is by the intimate experiences of this one character’s story.

How have people in Bogotá reacted to Narcos?

I’d be lying if I said that I didn’t get the sense that Colombians are over the Pablo Escobar story, or at least having their culture identified with that time in history. But having said that, being back in Colombia to film season two, seeing the friends I’ve made who have now seen season one—they love it. They find the country beautifully represented physically, and respect very much the clinical perspective taken by the show. Back in New York and L.A. people talk to me with a kind of fascination about how Americans are perceived. And in Colombia people are intrigued by the Americans’ perspective.

Jacket and shirt RAG AND BONE

Grooming by ELOISE CHEUNG @ KATE RYAN INC. Using DERMALOGICA

Do you have any words to live by?

Do you realize these are the hardest questions in the world? The first thing that comes to mind is “Don’t be a dick.”

And what will your dying words be?

“I hope I wasn’t a dick.”