Teeling Whiskey Single Barrel, Part 1

Quick nap back at the hotel. Luxurious trip to the steam room. Shower and a shave. Red-eye be damned, I feel like a human again.

Dressed in repurposed business attire, I accept roaming charges on my abbacus of a cell phone to fire off an email to the dog boarder. Phone not working. Available by email. Please confirm how Spud is doing.

If there were a course offered on guilty parenting, I could win Teacher of the Year.

Conor’s arranged for us to meet the waitress and a friend of hers for dinner. If I’m to understand correctly, in Dublin terms, this means drinks for an extended period followed by a snack later on.

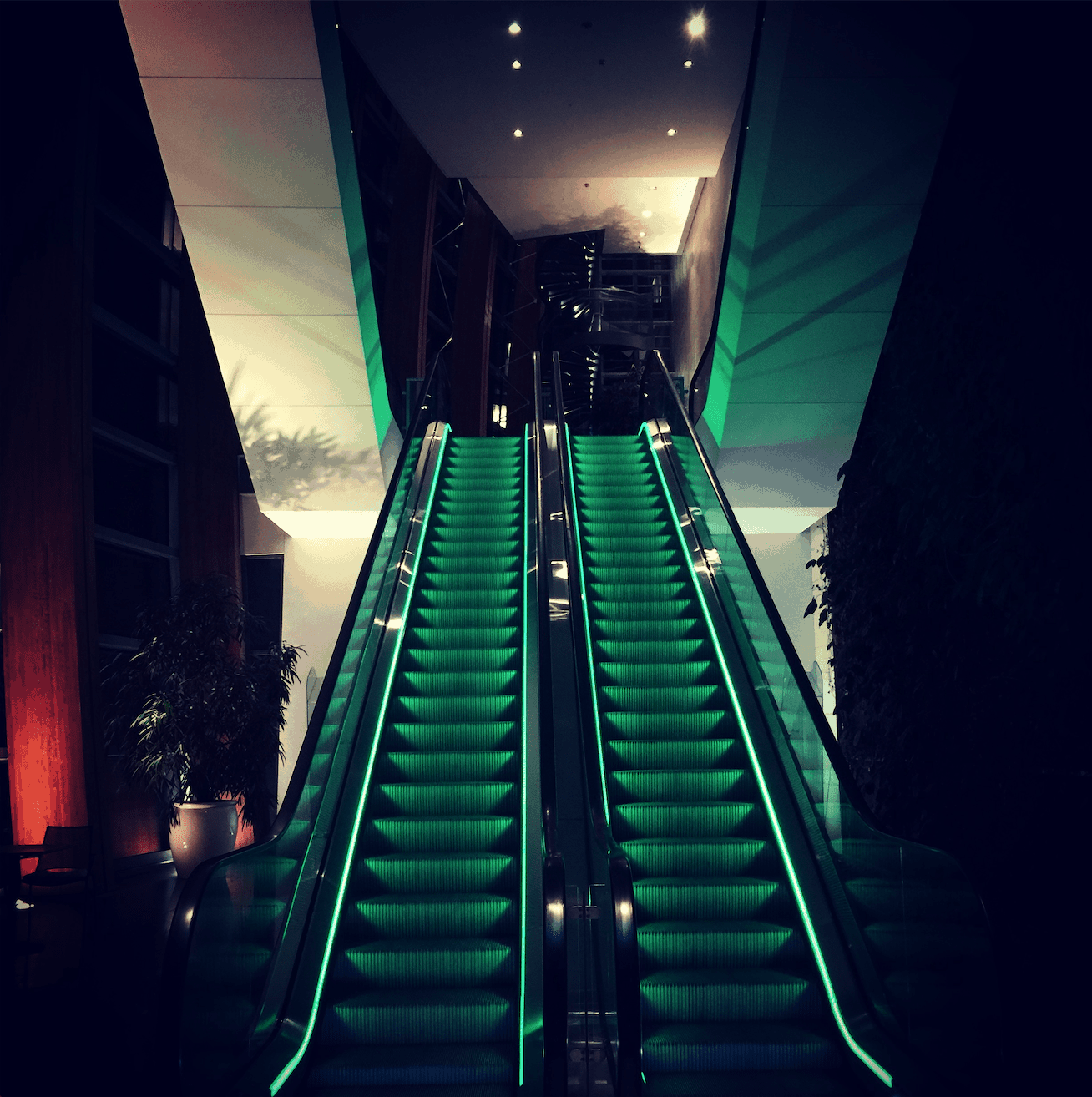

The hotel obliges me by calling a cab. It speeds away from my far-flung quarters toward the heart of the action. The bridges are lit for the night — some swimming in a simple warm glow, others shifting between hues that recall an underground club. The artfulness and variety between them. The sheer ballsiness of the city, allowing artists across two centuries to design each one as its own autonomous creation. It makes a man want to take up night photography. Click a shutter and stare. Let the world spin to a stop.

The Beckett’s a mad endeavor — the latest borne — a towering abstract harp on its side bathed in purple light. The O’Casey’s next on our joyride, a study in metallic geometry, sequential triangles dwarfing its pedestrians. The requisite utilitarian bridges follow farther on, accommodating the thoroughfare. Nonetheless, these wide, concrete roadways manage to preserve a hint of poetry thanks to some choice lighting. I’m reminded, riding across the O’Connell with the ghostly spire at my back, that this is where my predecessor met his fate.

We pull to a stop on the south bank. I disembark at the Ha’Penny — arguably the most photo-worthy bridge for its archways and intricate railings. A plaque informs passersby that the name comes from the toll exacted by its original owner — the foremost ferryman at the time whose boats sunk often enough that the city forced him into building an alternative. He, in turn, secured profit rights for the next 100 years. Self-enrichment, in service to all.

The bar Conor’s chosen proclaims itself to all who enter. Monumental in scale. Decor befitting a bunker. Ancient trimmings, yet brimming with life. Citrus-colored light shines through whiskies I’ve never tasted. Hand-scribbled labels fall from each of their necks.

I find Conor and our guests for the evening tucked away in a back corner. He waves me over and greets me again with an embrace. The sweet, stale aroma of beer surrounds him, and it dawns on me that he hasn’t stopped drinking since I left him hours before. He re-introduces me to the waitress and her friend, then challenges me to spell their names.

“Let the American get a pint, will yeh?” asks the waitress, hint of reproach in her voice.

“Have a gas like,” he says.

“Well,” I say, glancing at the friend. “Shivonne’s sort of straight forward, isn’t it?”

“Long as you put the ‘b’ in the right place,” she says, winding a tendril teased black-red-blonde hair around her finger that — despite the back-and-forth dying — manages to achieve a harmonious discord.

“His talent’s putting the ‘d’ in the right place,” says Conor, “if you catch my drift.”

The waitress slaps his shoulder, calling him wicked.

“There’s a ‘b’ in Shivonne?” I ask.

“S-i-o-b-h-a-n,” spells the friend.

“I’m even less confident with ‘Ee-fuh,’” I say, turning to the waitress.

“A-o-i-f-e,” the waitress says, tilting her glass. “Now, then. Good on yeh for a drink.”

Behind the bar, there’s an upturned cask of Powers and inverted litres of Jameson, to say nothing of the mystery bottles standing along the mirror. The bartender asks if I’m doing alright, I answer yes and lean forward to order only to watch him walk away. I’m told by the man beside me that this was his way of asking whether I needed a drink or not. Thankfully, the bartender returns after another two customers. I ask if he has a recommendation among the nine different types of Jameson. In reply, he says, “Jameson is the Jack Daniel’s of Ireland.”

I laugh. “Shit, huh?”

“Not shite,” he says, “not rainbows, either. Have you tried Teeling’s?”

He pours me a small glass of the distillery’s Single Barrel and has me close my tab on the spot. What starts as a sharp, abrupt first sip transitions into the whiskey equivalent of a lasting hug. I rejoin my party, where Conor and Aoife have drawn closer. No sooner have I clinked my glass to Siobhan’s half-pint than she asks if I’ll join her outside for a smoke. “Sure,” I say, stealing a sip and following her out the side door.

The cobblestone alley way’s pure Europe — all low light and shadow and storefronts manning the ground floor of every residence. I breathe in the fact that work has brought me to this most excellent city, that it will continue to bring me here, that this has somehow become my life.

Siobhan’s dressed with more than a touch of burlesque for the night. Tight leather jacket with faux fur exploding from the sleeves. Draping satin blouse begging to be ripped. Too-short skirt emphasizing fishnet-clad legs. Paired with her fair complexion and blue eyeshadow, she carries the overall impression of an exceedingly sexy birthday clown.

She lights a long, skinny cigarette and exhales with a short burst. “Thanks for coming out,” she says, offering me the pack. “Fairly certain they were getting handsy under the table.”

I withdraw one of her cigarettes, the first I’ve had in at least a year. It’s smooth as air, only a hint of burn and something herbal. “So, what do you do?” I ask.

“I work in a flower shop,” she says.

“What, like, making arrangements?”

“In a pinch, yeah. Mostly, I answer the phone.”

A trio of stout men pass us, hanging onto each other and shouting all the way down the block. “Do you have a favorite flower?”

“I hate flowers,” she says.

I cough, laughing. “That must be a pretty bad job for you, then.”

“Absolute shite, yeah.”

“Why don’t you quit?”

“Well,” she says, pursing her lips, “the pay’s terrible, it’s far from me apartment, and I’m not allowed to smoke within a block of the store.”

“I see.”

“I figure, if I start young, I can have several decades of missed opportunities and piss poor jobs.”

“Aiming high,” I say.

“I am, I am. Unless, of course, I get hit by a bus or something like Morris, the cunt.” She points her cigarette at me. “By the by, only I’m allowed to use that word, not you.”

It takes a moment before I unpack her remark. “Wait, you knew Morris?”

“Oh, sure. Always good craic. Conor not tell yeh?”

I smile, breathing smoke. “He pretended to pick up your friend in front of me when we went to lunch.”

“Took yeh to the touristy place?” she asks. “S’pose he must really want to have a gas with yeh. That menu’s ghastly.”

“Well,” I say, “I won’t give it away you told me.”

“Have you seen him? He’s locked out of his tree like a monkey who forgot his keys.”

As Siobhan steps into a patch of light, I spy the laugh lines on her face. “Can I just ask, how many ways do the Irish have of saying somebody’s drunk?”

“You mean scuttered?” she says with a wink. “We know what we know. You should hear how many we have for rain.”

[To be continued]

—

This piece appears as part of a serialized fiction experiment by Nathaniel Kressen for At Large magazine. New installments are published weekly, each based around a different liquor.

Nathaniel Kressen is the author of two novels — Dahlia Cassandra (named Best of 2016 Fiction by Entropy & Luna Luna Magazine) and Concrete Fever (Bestseller, Strand Book Store) — as well as the co-founder of Second Skin Books and the leader of the Greenpoint Writers Group.