Belvedere

Summer arrives in the city, abrupt and ruthless. The trees blossomed months ago, before winter clawed its way back. Their branches are in a state of utter confusion.

Overnight, the streets are paved with youth for whom clothing appears to be optional. (Youth will be defined here as anyone under the age of thirty.) They pack the subway cars during my morning commute, skin glowing. I have no idea where these people work. For some reason the train car blasts heat out of its vents. Our collective sweat mingles on the air.

Pompadour calls in sick.

I sit through two morning meetings, discover Conor’s offsite again, consider my inbox. I brave the hot sun at lunch and make a judgment call. “Working from home this afternoon,” I type. The words shoot off into the ether.

At last, someone’s fixed the entrance to Esther’s building. I buzz twice before she answers. Upstairs, the door to her apartment is ajar. The window to her fire escape is open. Hot, humid air infiltrates the living room.

“Hello?” I call.

She emerges from the bathroom, glass of vodka in hand. “I’m here,” she says, with a rasp, weaving toward the kitchen.

I peel off my suit jacket and drape it over a chair. She hands me a rocks glass filled to the brim. Her eyes are flat, emotionless. “Is everything alright?”

“Fine. Drink.”

“What happened?”

“Okay, I’ll drink it,” she says, snatching my glass back and heading for the couch. She drops onto the cushions, liquor sloshes onto her lap. She takes a sip from each hand and her body deflates, head falling back.

I circle behind her. “Talk to me,” I say, rubbing her shoulders.

She shrugs me off. “Look out there.” I’m a step or two toward the window when she says, “That stray cat fell off the fire escape.”

“No.”

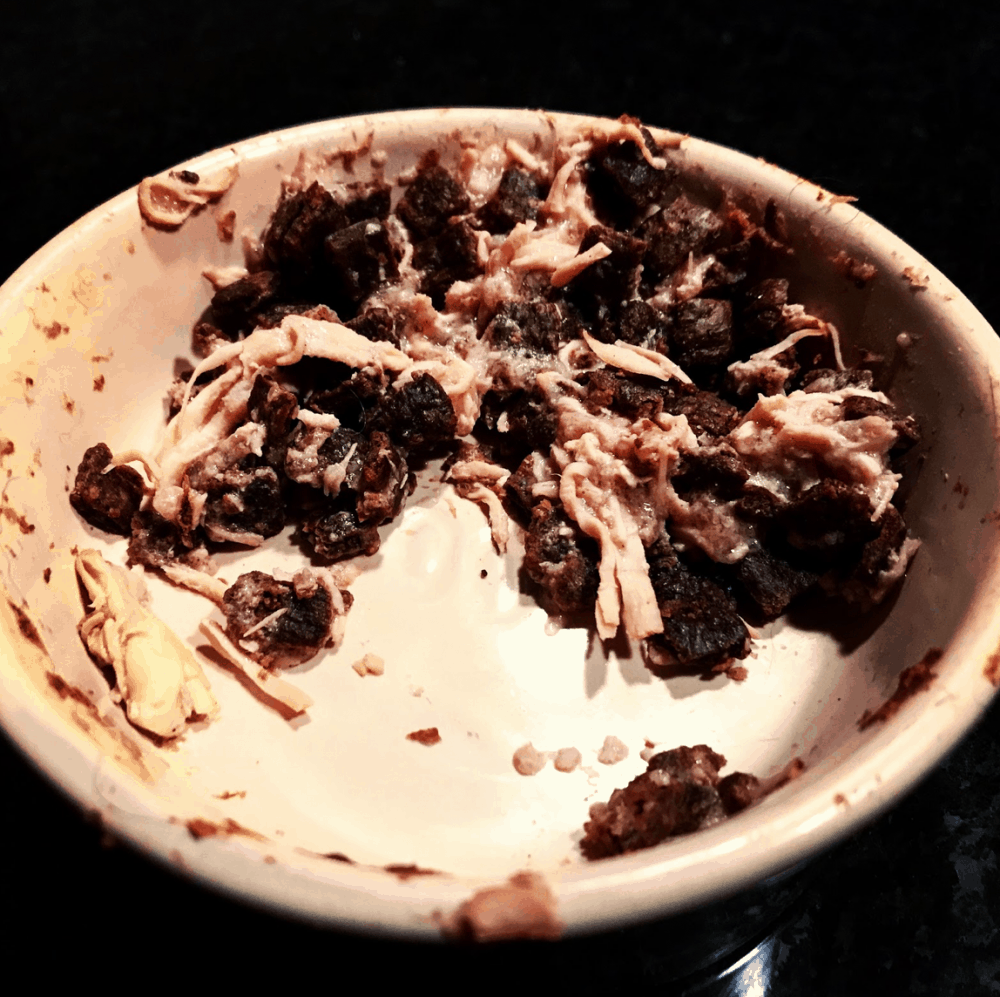

“One minute, it was eating out of the bowl. Next, slipped.” She toasts the air. “So much for good deeds.”

“I’m so sorry,” I say.

“It wasn’t my cat,” she says. “Belonged to nobody.”

“Should we do something?”

“Someone will take care of it.”

I take a step toward the window.

“It’s not pretty,” she says, through a cloud of vodka.

I crawl onto the fire escape and look down toward the alley. There’s no wind. It’s as though the atmosphere’s given up.

Returning inside, I linger by the window. Esther is drowning herself. The bag of cat food sticks out of the trash.

“I’m going down,” I say.

“There’s nothing for you to do,” she says, turning on me. “It was a stray cat, it belonged to nobody, dead is dead.”

“Maybe.”

She sets down her glasses with a thud. “Wouldn’t you rather fuck me?”

“Come on.”

“Come on, what?” she says, launching onto her feet. “You’re always so considerate when we do it. So thoughtful. Don’t you want to give me what I deserve?” She grabs my belt, pulls me clumsily against her. “I want you to treat me like trash, okay?” She bites my ear. “Do whatever you want.”

I pry us apart. “Let me do this, okay?”

She sways. Blinks. “I am literally throwing myself at you.”

“This isn’t you,” I say, stepping outside.

The alley is closed off from the street by a gate, making the fire escape the only option. Climbing down, I’m able to peer into every apartment. Thankfully, only one family is home at this hour — a mother reading while her daughter plays. The young girl spots me, she’s four or five at the most. I wave and she waves back.

The fire escape ends ten feet from the ground, the ladder is stuck. I sit with my legs dangling, then attempt a pull-up position for the first time since grade school. Offering a half-prayer to whoever’s listening, I let go.

Up close, it becomes obvious that I could have never stomached being a vet. Kitty must have strength beyond measure. I cover Belvedere’s body with a section of newspaper.

For a minute, I merely stand there. What was the plan, here? Throw the poor thing in the trash? Borderline worse than ignoring the situation altogether. I glance around the trash bins, recycling bins, discarded furniture. Is a funeral pyre out of the question? Undoubtedly. I kick the ground. How do you bury something in New York?

The solution presents itself as though answering a riddle: You build.

I prop open the gate to the street and head to the corner deli, select a bouquet of dark roses and ask for multiple plastic bags. Returning, I set the flowers on a trash lid and shove my hands inside the bags. Carefully, I wrap Belvedere’s body in yesterday’s Times.

To the rear of the alley is a chain link fence. I carry his body to an out of the way corner, somewhere he’s unlikely to be disturbed. I gather bricks and broken pieces of cement, building him a tomb.

I turn back for the flowers and see Esther watching from above. I signal for her to take the stairs inside rather than the fire escape — fearful at her level of drunk and the final jump that my right ankle’s still feeling. She disappears into the apartment.

An ambulance passes. A car alarm goes off. There’s bursts of loud music and liberated schoolchildren.

At last, Esther materializes at the gate wearing a simple black dress. We meet by the flowers.

“I couldn’t not do something,” I tell her. She nods, eyes fixed on the tomb. She allows me to hold her hand, and together we walk as though facing the firing squad.

I offer her the flowers, she wants me to place them. I ask if she’d like to say a few words. Again, she signals for me to do it.

“We’re here to say goodbye to you, Belvedere. You belonged to nobody but we really liked having you around. You were a good boy. You were always a good boy.”

Esther hasn’t shed a tear since I’ve known her — not that I’ve witnessed, anyway. Even in the thickest of late night drunks, not a single one. On this occasion, with city sounds echoing off the walls around us, life being lived as though we haven’t just lost a friend, she breaks down so suddenly, so forcefully, that I’m lucky to catch her before she hits the ground.

She is beyond sobbing as I lead her out of the alley. We enter her building behind a neighbor who opts not to get involved. With one flight to go, she collapses in the stairwell and heaves in short spasm breaths. Her face goes red, she buries it in her hands. I collect her in my arms, she clutches me in hers, and I carry her the rest of the way.

—

This piece appears as part of a serialized fiction experiment by Nathaniel Kressen for At Large magazine. New installments are published weekly, each based around a different liquor.

Nathaniel Kressen is the author of two novels — Dahlia Cassandra (named Best of 2016 Fiction by Entropy & Luna Luna Magazine) and Concrete Fever (Bestseller, Strand Book Store) — as well as the co-founder of Second Skin Books and the leader of the Greenpoint Writers Group. He was commissioned by At Large magazine to publish his third novel in serialization — now available, with new chapters publishing weekly — titled My Life on Rye. And, as one half of the wife-and-husband team Grackle + Pigeon, he’ll be publishing a tome for modern living this fall — Blanket Fort: Growing Up Is Optional (HarperCollins/Morrow Gift). You can find his work at nathanielkressen.com.