In The Realm of Perfection

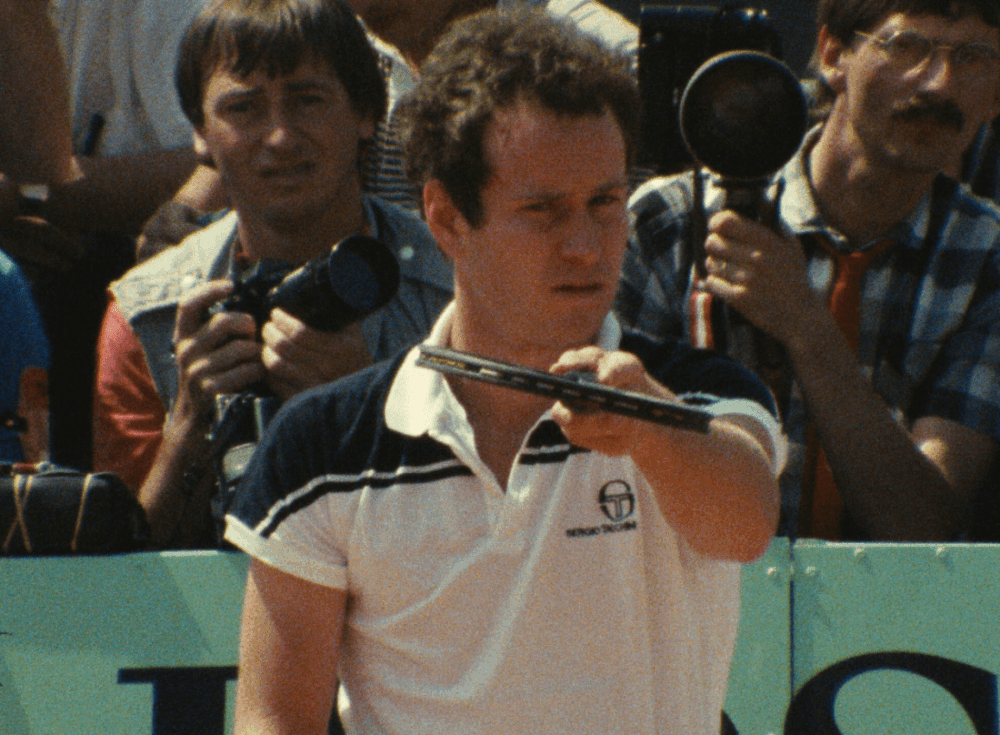

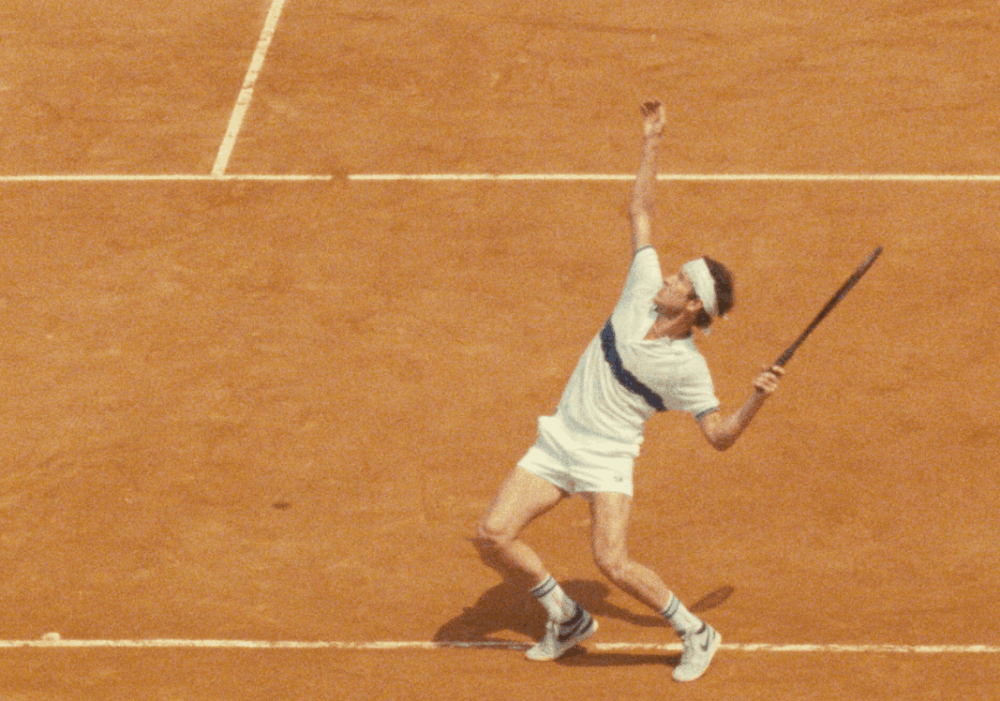

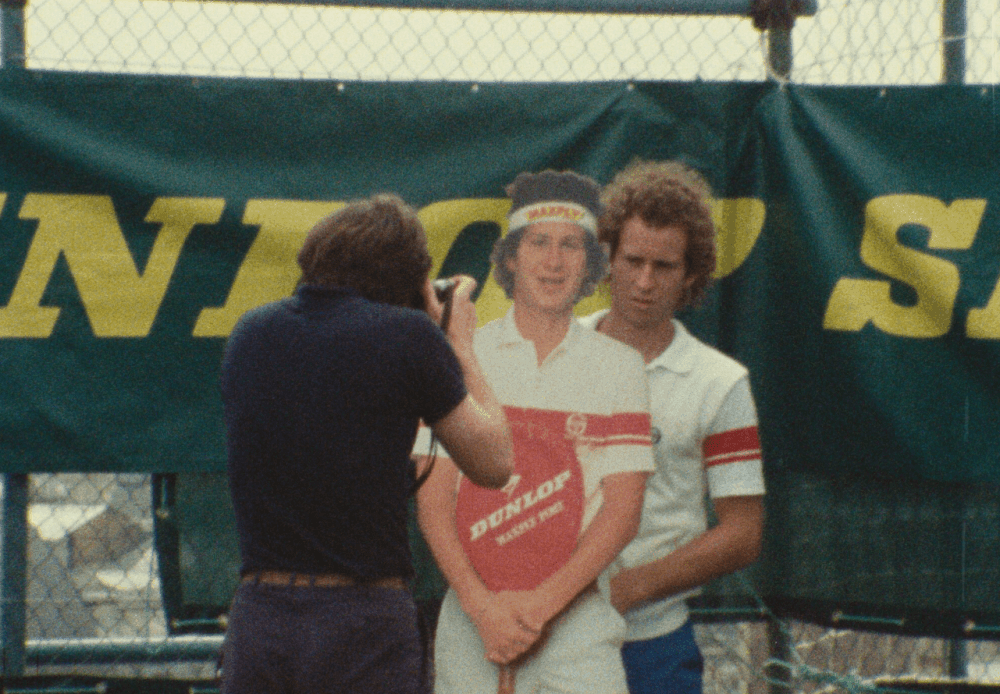

Film still from In the Realm of Perfection

Why is In the Realm of Perfection so hard to write about? I mean, I loved it the first time I saw it. It did everything a documentary should do. It engaged me. It even provoked me to tap two chatty men on their shoulders and tell them they were keeping me from being spellbound in darkness. Going to the Seattle film festival as a critic has its perks and one of them is being able to see films with paying albeit intense audiences.

Seattle takes movies seriously; their beloved film festival lasts a month and sells out and out of town press are welcome but not revered. Here’s the thing, I have no idea how many movies I’ve watched in the last year but it is certainly more than 200 and the notion of being transported to another reality for a couple of hours grounds me in my own. The cognitive dissonance we experience when we watch a movie that allows us to disavow our surroundings, our world for the duration of the film is what makes films magical. It is not limited to narrative films but includes documentaries (or at least the good ones). Another thing: I’m a junky for sports documentaries or, to be clear, at least documentaries about people who play sports at an elite level. Perhaps it is because I was often picked last. I don’t begrudge these athletes their success, instead I am obsessed with it.

In the Realm of Perfection begins with an epigraph by Jean-Luc Godard: “Cinema lies, sports doesn’t.” Wait a hot minute. We are watching a documentary that questions the very nature of documentary filmmaking. I keep asking myself if the film is about tennis, or about McEnroe as a player or about POV? None of the above, all of the above? Why tennis? Why McEnroe? Why use an antiquated instructional video on how to play tennis throughout the film? Is the use of an instructional video a metaphor for how not to go through life? The second time I viewed the film the Godard statement about Cinema lying and sports telling the truth shook me for days. Can perfection ever be achieved? Can perfection be taught?

So, the instructional video breaks down the mechanics of tennis playing. It dictates step by step where to place your feet, what angle to hold the racket, when to swing the racket. What it doesn’t take in account for is that tennis is not played in a vacuum. What makes this video so compelling is the hilarity of the absurd. The video also serves as a reminder that not everything has to make sense to be perfect. John McEnroe does not make sense.

McEnroe does not scream ideal specimen of an athlete. With his shirt off, he sports an almost pre-adolescent physicality. It almost made me want to look away. Like for some reason I shouldn’t be looking at this childlike man with his shirt off. Childlike in that he famously threw temper tantrums? Childlike because he looked like an elongated little boy? I grew-up watching McEnroe play tennis. He made a sport where the goal is to get a fuzzy yellow ball over the net two times more than your opponent by the end of the match and if tied those two points must be two times in a row, breathtaking. McEnroe gained a reputation as a bad boy of tennis. He fought for every point that he believed belonged to him. He was fierce and like any frustrated toddler unable to find his words, he was righteous in his indignation when something didn’t go his way. Failure to accept mediocrity does not make a person arrogant. Thinking you’re better than everyone else and not bringing it does. McEnroe can never be accused of not bringing his entire self to every match. He “…played on the edge of his senses.” It’s easy to see the French director, Julien Faraut’s fascination with McEnroe. If you think about the idea, “the image we have of ourselves rarely ever tallies with the image others see,” you might lie awake all night. No two people see the same thing. How the world sees McEnroe bears no relevance on how he sees himself. He is impervious to feedback. The actor Tom Hulce who played Amadeus took inspiration for his petulant, over the top character from watching John McEnroe play tennis. McEnroe won because he played against himself. At least in the movie, Mozart scored symphonies on his death bed because he could.

But why does Faraut warn us at the beginning of the film that cinema lies? No matter how many cameras, regardless of instant replay, forget slo-mo, someone has to decide where to put the camera. There is always a point of view and therefor more than one way of seeing something. How we see the world two dimensionally through film depends on someone else’s perspective. Speaking through the voice of narrator, Mathieu Amalric, Faraut warns us to be skeptical because cinema lies. The film works because it shows us over and over not to believe everything we see. That players behave differently when they know they’re being filmed then when the camera is out of sight. Watching a documentary of a film in 16mm takes us out of the world of cinema vérité and into the realm of fiction where anything seems possible. Where knowing the results of the 1984 French Open that destroyed McEnroe is suspended just long enough for us to believe that he just might beat Ivan Lendl—not perfect, but close.

—

Written and Directed by JULIEN FARAUT

Produced by WILLIAM JEHANNIN and RAPHAELLE DELAUCHE

Narrated by MATHIEU AMALRIC

World Premiere: 2018 Berlin International Film Festival

Run Time: 95 minutes; Not Rated

Check local listings for screenings

SIFF 2018