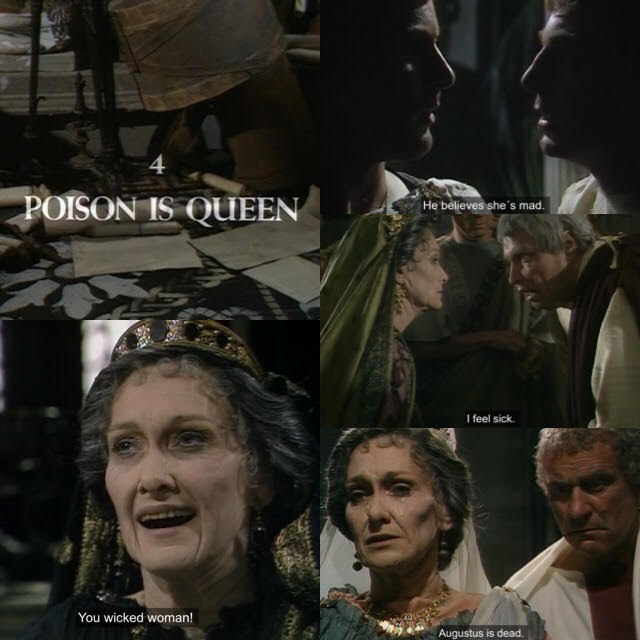

Poison is Queen

I, Claudius: Episode 4

On a sweltering 4th of July in 1850, U.S. President Zachary Taylor spent the heat of the day attending an open-air speech at the unfinished Washington Monument near the U.S. capital. The 65 year-old former general was reported to have kept hydrated with water during the event, before returning to the White House with a strong appetite. He cooled down by feasting on berries, cherries, and iced milk. Later, he ate a dinner that reportedly included cabbage, cucumbers, and more cherries. After dinner, he suffered an onset of gastrointestinal pain that worsened over the next five days into dysentery, vomiting, fever, and then his death on July 9th.

The cause of death at the time was diagnosed as “cholera morbus”, which served as a catch-all term for unspecified gastrointestinal problems. 140 years later, though, Taylor’s body was exhumed and examined to see if his hair, nails, and teeth contained arsenic. They did indeed, but not poisonous levels, so Taylor’s death was diagnosed as stemming from natural causes.

The case for Taylor’s assassination by poison has relied on the political circumstances of his presidency at the time of his mysterious death. While in the military, he was instrumental in expanding U.S. dominion over North America with victories in the Black Hawk War, Second Seminole War, and Mexican-American War. However, even though he was a slave owner, Taylor was opposed (to the anger of his Southern supporters, like son-in-law and future Confederate President Jefferson Davis) to expanding slaveholding into future western U.S. states of California and New Mexico.. So, did President Taylor’s politics cause his death? If so, it wasn’t by arsenic — a poison that has killed as far back as the last days of Augustus Caesar.

In 14 AD, Brian Blessed’s Augustus is struck by two bouts of a mysterious gastrointestinal affliction. The first he weathers by forgoing meals from his palace kitchens. Instead, he orders a cow brought to him, drinks only milk that he extracts himself, and eats only fruit that he picks from his garden. He soon recovers. But we are shown the political cause of this close call. Livia has discovered that Augustus plans to make the banished Postumus his heir, instead of Tiberius. This change of heart is brought on by Claudius, who uses the same tactic that Livia employed to remove Julia: a trusted messenger bringing bad news to Augustus. In this case, the messenger is Germanicus, and the bad news is Livia’s role in Postumus’ rape charge, and the many mysterious deaths within the Julio-Claudian family. Claudius convinces Germanicus of Livia’s true nature during a hushed palace conversation:

Claudius: “If you’re in a mood to listen, I’ll tell you what Postumus thinks of her — and what he thinks will stand the hairs up on your head. He believes that over the years, she has systematically destroyed his mother, his two brothers, and possibly his father Agrippa. He believes she poisoned Julia’s first husband Marcellus, and had a hand in our father’s death when he saw what she was doing. He believes that she poisoned our grandfather. He believes she will stop at nothing to ensure that Tiberius follows Augustus. He believes she’s mad.”

Finally believing Livia’s treachery in advancing Tiberius, Augustus pretends to be slipping into senility, so as to hide his true plans from his wife. He takes a secret sea journey to the island where Postumus has been banished. There, he offers a tearful apology, and declares his intention to return Postumus to Rome. During their tense conversation, though, Postumus warns that Augustus should worry about Livia’s reaction to his plan, and the aging emperor notes how 50 years of married familiarity have made acknowledging such fear difficult:

Augustus: “You live so long with a woman, and she’s been more than a wife to you. It’s been like having another right arm. It’s hard to believe such things.”

Eight years before I, Claudius aired on the BBC, Granada produced a theater-style mini-series covering the Julio-Claudian emperors, titled The Caesars. Like I, Claudius, this 1968 production depicts Augustus dying in his bed, but with some notable differences in conversation. In The Caesars, he converses with Tiberius, explaining his reasons for marrying Livia in the first place:

Augustus: “When I first met your mother, I was 24, married to a middle-aged woman who nagged me. I’d been at the war since I was 19. Civil war. You’re too young to understand what that means. It means that when you win a battle, you kill 1,000 of your own old friends. The flower of your own country’s manhood.”

Tiberius: “Clichés from your own old speeches, Caesar.”

Augustus: “When I met Livia, she was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. And she had the strength of character I needed to support me through the war.”

Tiberius: “You should also mention that her family was one of the oldest in Rome, with great political influence, which did much to further your career. You were born under a lucky star, Caesar. Ambition and pleasure have walked hand in hand.”

This Augustus dies surrounded by family and royal court members — all of them following his order to applaud, and filling the room with echoing hand claps as he finally succumbs. The death of Augustus in I, Claudius is quieter, with the camera settling on Brian Blessed’s unblinking open-mouthed expression for a full three minutes as he gradually dies from Livia’s poison, while she mournfully expresses frustration with her role during his long reign.

Livia: “You should have listened to me more. You should have. You know that, don’t you? I’ve been right more often than you have, you know. But because I was a woman, you pushed me into the background. Oh, yes. Yes, you did. And all I ever wanted was for you and for Rome. Nothing I ever did was for myself. Nothing. Only for you, and for Rome… as a Claudian should. Oh yes, my dear, I’m a Claudian. I think you were apt to forget that at times. But I never did. No, never. No.”

Livia’s hand enters the shot and closes Augustus’ eyes. Then, a reverse shot as she brings the hand to her own tear-filled eyes. It’s the emotion of murdering her spouse of 50 years — a fact the audience is reminded of when Tiberius enters, and Livia tells him not to eat any of Augustus’ nearby garden figs (implying that she has poisoned them all).

Livia then dispatches the Praetorian guard Sejanus to execute Postumus on his tiny island, clearing the way for Tiberius’ uncontested ascension to emperor. The episode closes with Claudius stammering his condolences to a contemptuous Livia, who relays her intention to one day be named a god like her late husband. She then mocks and laughs at Claudius — the echoes filling the ears of his elderly version, who shouts with rage at her now-long-empty seat:

Poisonous queen! Poisonous queen!