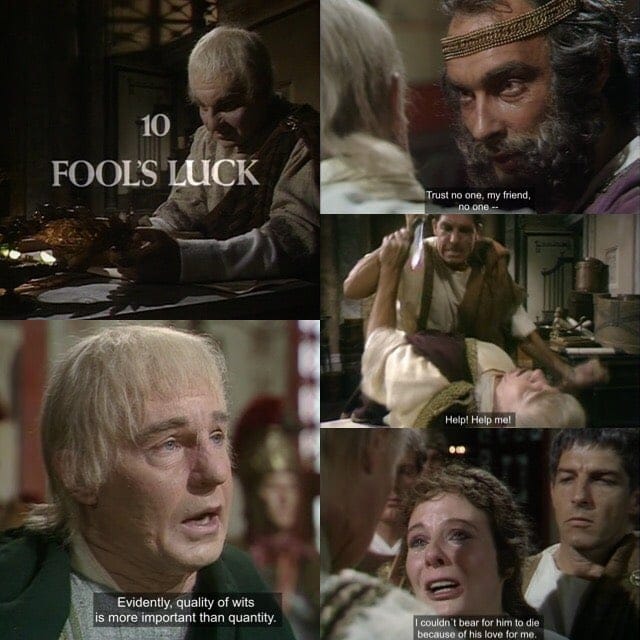

Fool’s Luck

The finest portion of Charles Laughton’s abbreviated 1937 film turn as Claudius is his first speech as emperor to an assembly of Praetorians, senators, and the arrested conspirators who killed Caligula — concluding with his judgment of chief plotter, Cassius Chaerea:

Claudius: “Caligula was murdered. He ruled by force. But a state such as the one I hope to establish cannot condone murder. For violence is an enemy to justice, and in the name of justice, I call upon the murderers of Caligula to step forward.”

Cassius: “We killed a tyrant, Caesar.”

Claudius: “But you broke your solemn oath as Roman soldiers to protect your emperor. You didn’t strike for your country. You killed in the name of your own private grudges. I was with you, Cassius, when the tyrant kicked you. But you were not content with one single murder. You caused the death of Caligula’s wife, and of hundreds at the palace. What fate do you consider you deserve?”

Cassius: “Death, Claudius.”

Claudius: “For that answer, I will take your families under my protection. But for the crime of murder, I must sentence you Cassius, and you Lupus, to… death.”

Laughton’s naturalistic performance in I, Claudius was greatly admired, even 28 years later, by his fellow cast — who also recalled the crippling self-doubt that plagued every scene he filmed. In the 1965 documentary about the doomed production, The Epic That Never Was, host Dirk Bogarde critiques Laughton’s first speech as emperor thusly:

Laughton here proved he was kissed by genius, and I’m not in the least surprised that he went through agony and despair to bring Claudius alive to the screen. Because to me, in that scene, Claudius is alive, and resurrection is never easy.

Indeed, it was the phenomena of Laughton’s difficult genius that made even an unfinished I, Claudius worth producing a documentary about 28 years later. The film’s Caligula, Emlyn Williams, dove deeper into what made Laughton worth the neurosis he brought to preparing and playing Claudius:

He’s one of the people who you could really apply the word ‘genius’ to. It’s a very difficult word to really live up to. But when Charles was at his best… no other actor can quite do it the way he does it. And of course he was difficult. Anybody like that is difficult. He was a child. He was a brilliantly gifted child who had this instinct for acting. He had a complex about his appearance. He was a brilliantly natural instinctive actor, but he wanted to rationalize his performances. He wanted to feel that he really was governing them with his intelligence.

Laughton had been recruited by producer Alexander Korda, after working together on successful films, The Private Life of Henry VIII and Rembrandt. However, when Josef von Sternberg came on to direct I, Claudius, he inherited the casting of two stars he had never worked with: Laughton and Merle Oberon (as Messalina) — and by all accounts, Laughton’s need for constant reassurance proved a terrible match for the cool distant demeanor of his director. 39 years later, though, the pairing of Derek Jacobi and Herbert Wise worked out far better. Already familiar with each other from their work on TV project Man of Straw, the two would need a good rapport, as their working relationship had to remain productive over six months of technically-complicated studio filming — including excruciatingly long hours of daily make-up application and removal for Jacobi’s older years. Laughton never would have tolerated such artificiality, but Jacobi had no such qualms — and it adds an important physical aspect to the 50 year-old Claudius’ first speech as emperor, which is not seen upon the prosthetic-free face of then-37 year-old Laughton during his rendition. Jacobi’s mask of meticulously-applied old age skin reinforces the doubt that Rome’s senators have of their new leader’s physical and mental competency for his job. Yet, for each of their doubts, Claudius has a ready reply:

Hard of hearing: “But you will find it’s not for want of listening.”

Speech impediment: “But isn’t what a man says more important than how long he takes to say it?”

Little government experience: “But then have you more? I at least have lived with this family who have ruled this empire ever since you spinelessly handed it over to us. I’ve observed it working more closely than any of you. Is your experience better than that?”

Half-witted: “Well, what can I say? Except that I have survived to middle age with half my wits, while thousands have died with all of theirs intact. Evidently quality of wits is more important than quantity.”

He concludes with an assurance… and a warning:

Senators, I shall do nothing unconstitutional. I shall appear at the next session of the senate, where you may confirm me in my position, or not, as you wish. But if it pleases you not to, explain your reasons to them (motions to the Praetorians), not to me!

Claudius does not prosecute the conspirators for killing Caligula (setting free royal brother-in-law Marcus Vinicius), but sentences Cassius Chaerea to death for taking it upon himself to kill the empress Caesonia and her child. The proud soldier declares he would have added Claudius to the dead, to ensure the return of a republic, and shouts a final warning as he is dragged away:

Congratulations, Caesar, you’ve passed your first sentence of death. How many more will you pass before they grow tired of you, and pass one on you? Isn’t that the way we’ve set for ourselves? Think about it, Caesar! Think about it!

Instead, Claudius focuses on cleaning up Caligula’s mess, and enlists the help of his ambitious teenage wife (who Caligula forced him to marry as a joke) Messalina, and his old friend (now with kingdoms of his own) Herod Agrippa — who eventually takes his leave of Claudius (once reforms have begun) with a parting piece of advice:

Trust no one, my friend. No one. Not your most grateful freedman, not your most intimate friend, not your dearest child, not the wife of your bosom. Trust no one.

Those words will prove prophetic for each of the four examples (as well as Herod himself) — most immediately regarding Messalina, who manipulates Claudius into transferring the governor of Spain, Appius Junius Silanus to Rome to be a royal advisor, and to marry her mother. In truth, Messalina has a long-standing obsessive crush on Silanus, and tries to blackmail him into being her lover by, in part, misrepresenting Claudius’ knowledge of the arrangement (while portraying the emperor as a Caligula-like tyrannical sexual deviant). When the honor-bound advisor tries and fails to assassinate Claudius, he is spared for questioning. And though Messalina and (grudgingly) her mother lie their way out of blame, Silanus is sentenced to death for his attempt — upsetting the short-sighted Messalina, who only wanted him banished.

Yet, even after this episode, Claudius remains ignorant of his wife’s treacherous nature. The stage is set for Messalina to leverage that ignorance into a run of competitive sexual pleasure-seeking, and a deadly plan to take Claudius’ imperial power for her own.