Dirty Bomb — A Little Known Holocaust Story and Interview with Actor Ido Samuel

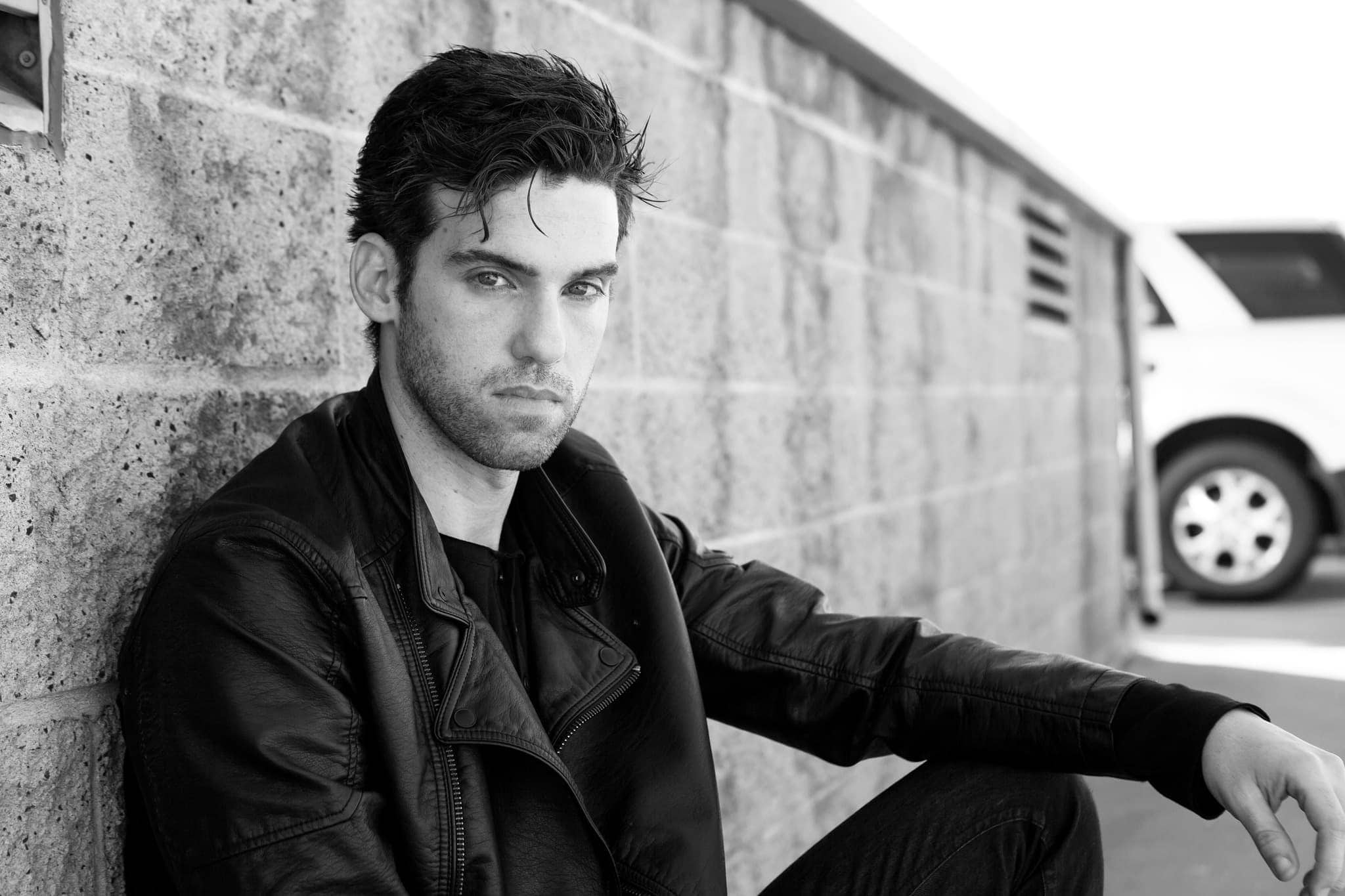

Ido Samuel | Photo by Lesley Bryce

Ido Samuel is not the first actor to radically change his body for a part but he is one who bore the responsibility of a story so much bigger than himself that he didn’t feel like he had a choice. Written and directed by Valerie McCaffrey, Dirty Bomb is a short film being made into a feature about a group of Jewish scientists who were forced to work on the Nazi V-2 bomb project while interned in Mittelbau concentration camp. They wrote their identification numbers on the sides of the bombs in case they didn’t explode or were sabotaged, which is exactly what some of the men did. During the war, over 200 of the most destructive bombs were prevented from detonating saving the lives of thousands but ensuring imminent and often tortuous death of the scientists who caused the failures. In person, Samuel, who is from Israel has uncanny blue eyes, dark curly hair, fair skin, and a lean build. To play the emaciated Aharon, the actor starved himself for weeks to transform himself into a believable concentration camp prisoner.

I chatted with the actor during the Tribeca Film Festival at a café in the East Village. Samuel talked about preparing for his role as a concentration camp prisoner to try to understand the survival instinct of the Jews in the camps.

The following excerpt is edited for brevity and clarity:

On telling a little known story outside of Germany

I’m from Israel and I didn’t know about [the story] and we never stop studying the Holocaust. Throughout school, Holocaust survivors come and tell us their stories so when Valerie, the director, told me about the story I was shocked that I didn’t know about it, and then I did some research and I found out a little more and I’m like, how come no one knows about it?

The Medium of Film

And the best way nowadays to tell a story is film, so that’s why Valerie wrote the short. It’s easier to make a short film before making a feature. We won the Madrid Film Festival award for best short film, we were in Cannes, and all the big festivals.

We are getting great reactions, which is [validating] because we just wanted to tell the story. But when we shot it, FOX News, CBS, and other media came to the set. Because we shot it in Fresno, California, in one hundred degrees, we were all sweaty and we were supposed to act like it was freezing cold. So every time they yelled cut, someone came and wiped up all the sweat.

It was misery, but it’s worth it, to create something like that— you feel the importance.

Dirty Bomb | Photo Courtesy Valerie McCaffrey

On the mental toll of playing a concentration camp prisoner

I saw a lot of interviews with survivors, so my mindset, physical and mentally was very down. Also, it took me months to recover from it mentally. As an actor, it’s rare that you get a story that important. It’s part of your job to tell a story, It’s important as a Jew to honor these people.

On Holocaust deniers

Also, when we started shooting, there were a few articles about a lot of people denying the Holocaust. Everything made me determined to do the best performance I could in this film.

Photo Courtesy Valerie McCaffrey

What Ido Samuel took away

When the war was about to end, the Nazi’s wanted to destroy all the evidence at the camps. They just burned everything—killed everyone in the camps. Before we shot the film, I met a survivor from Mittelbau. I imagined I would just kill myself if I saw my family and everybody around me murdered. I don’t want to help the Nazis; I don’t want to be in that situation. So, I asked him what kept you going? He said he had a brother in the same camp who didn’t work on the bombs. His job was taking the clothes from the dead bodies for the new prisoners and digging graves for the dead bodies. He said once a week, he got bread, and his brother didn’t get any at all. So, whenever he got bread, he took some of it and gave it to his brother and knew that if he ended his life, his brother would die. He said the feeling of hunger was the most powerful feeling they had. That’s all they thought about. They didn’t have time to think, “oh, my family’s been killed.” They just thought about surviving.

That’s why I tried to starve myself, not as much as they did, but just to have a little bit of that feeling. But what struck me the most, is what he told me about the last days of the war. When the Nazis left, they left behind a lot of the prisoners in the camp where everything happened, and the prisoners didn’t know the war was ending.

By then, his brother was really weak so he went to the forest by himself. The survivor I talked to, he’s ninety-two or ninety-three now; he went to the forest by himself, and after a few miles, he saw the dead body of a Nazi soldier, put on his uniform and decided to just go back to camp, because he didn’t want to die in the forest.

Then he saw that the Nazis coming out of the forest were going back to the camp to kill everybody so there would be no evidence—they killed his brother. He’s lived with the guilt to this day because he told his brother to stay in the camp, yet he got out. Stories like that, you hear them. We still have survivors. Alive. Not a lot of them, but yeah. When he told the story, he told it like it was yesterday. You feel his need of him tell his story. I can only imagine him seeing all these news reporters saying there was no Holocaust.

On keeping stories alive

Each person has his own story. I told you one story of one survivor and I wasn’t expecting to be the teller of the story. Every story could be a movie.