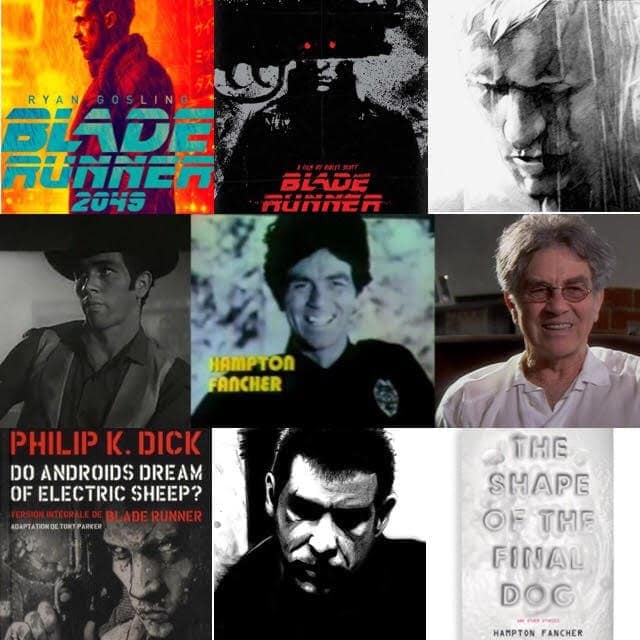

As Blade Runner 2049 opens nationwide today, the original film’s screenwriter, Hampton Francher reflects on books, screenplays, and Burroughs, Dick & Bukowski with At Large‘s Christian Niedan.

[Sapper:] Nobody ever sees me!

[Kard:] That’s not true, Sapper. If it was, I wouldn’t be here.

Sapper got louder.

[Sapper:] I work with objects, not people — I drive the tractor!

— Excerpt from The Shape of the Final Dog, by Hampton Fancher.

In the title chapter from his 2012 book of short stories, The Shape of the Final Dog, Hampton Fancher sets the scene in a lonely farmhouse of ravaged near-future Earth, where a human-like duplicant (or “steelhead”) named Sapper is hunted down by a tracker of his kind named Kard. If the dynamic feels cinematically familiar, that’s because the exchange is drawn from an excised portion of Fancher’s early screenplay for 1982 film, Blade Runner, directed by Ridley Scott. Though he is credited as executive producer, Fancher’s involvement with this massively influential science fiction movie (and its sequel, opening October 2017) runs far deeper. It was Fancher who set Blade Runner’s production in motion by optioning Philip K. Dick’s novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? in the mid-1970s [along with works by William S. Burroughs and Charles Bukowski], then worked as the film’s screenwriter, before giving way to David Peoples.

35 years later, Fancher is getting a second chance to make his writing mark on a Blade Runner film, as the co-screenwriter (with Michael Green) of Blade Runner 2049, starring Ryan Gosling and Harrison Ford, and directed by Denis Villeneuve. This comes in the wake of a recent documentary about Fancher, Escapes, that tracks his remarkable life and career — which included growing up a mixed-race child in 1940s Los Angeles, sailing to Spain as a teenager to become a flamenco dancer, acting in TV westerns during the 1950s and ’60s, taking the stage in an early production of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, writing and directing films in the 1980s and ’90s, and an offscreen lifestyle that was as salacious and fascinating as any of his film and television projects.

As showcased in Escapes, Fancher is a skilled raconteur in person, with a love of both poetry and prose, but has rarely published his own writing. So, in advance of Blade Runner 2049’s release, I visited Fancher at his Brooklyn Heights apartment, and recorded an interview about his off-screen writing life. You can listen to the the full audio interview, embedded above, but here are a few notable excerpts from Fancher — told in his distinct storytelling style:

On writing for print:

I think I was only offered one thing in my life, in fact. It was a New York Times piece on man’s dress for the Sunday magazine, I think it was, years ago. And it was somebody who was connected to them, nobody official, from their offices. And she said, “Do you want to do a piece?” And I said, “Yeah. About what?” And she said, “About clothes.” And I said, “Yeah, I’d love to do something about business clothing in modern times, like 19th century. How’d that happen? And I’ll write a piece on that.” And she says, “That’s great” So I did it, and I wrote a piece, stole some stuff from John Berger, and had a good time with it. And she loved it, and they loved it, and I chickened out, and I wouldn’t let them publish it. I don’t know why. I think it’s the Berger equation. Because I took some ideas from him, and I transmuted them, I hope. Anyway, that’s the only time, and then I published something in a magazine recently, and that’s about it — except for the book [,The Shape of the Final Dog].

On his own fashion sense:

I’ve never hankered after anything like that’s, say, conventional. I cannot have anything in my pockets. I can’t wear a belt. I don’t wear underwear. I don’t wear ties. I mean, I have a tie, but it’s rare that I wear it. I don’t like to be restricted physically, you know. And my parents thought the same, my sister too. And I’ve always gone my own way, fashion-wise. I don’t dress the norm, I don’t think, and I never did. And I look back on myself, and it embarrasses me. I mean, the shit that I’ve worn has been kind of absurd, you know, and I can’t believe I did it. You know, I was wearing that. I over-dressed. Since childhood, I’ve had ideas about how I wanted to dress. You know, romantic ideas of fantastical things. I thought I was in another world, you know, and that clothes had something to do with it. So I dressed oddly, I think. From about 17 to about 20 I thought I was [Crime and Punishment protagonist] Raskolnikov. I mean, I dressed like a Russian tramp, like a bum, you know, torn clothes. I dressed for a while, I remember, with sailor pants that were skin tight, and an old suede jacket that was something I’d found in an alley, you know. I went through periods of stupidity. I mean I can’t believe it, that I did that.

On writing screenplays, versus writing a book:

I never thought there was a difference. I mean, screenwriting is restrictive much more. I mean I was glad to do the short stories, because screenwriting is a very confining mode of writing. It’s in a little particular channel, and it’s arduous. To make all the things you want to do, you can’t do, because they have to be here and now, and prose don’t make such a difference — and style, prose, etcetera make a huge difference in other kinds of writing. And that’s one of the reasons it always took so long for me to write a screenplay, because it did make a difference to me, and my screenplays were always… I had some kind of conceit about the way I put words on the page. And I wanted them to be distinctive, and beautiful, or strange, or whatever I wanted. But I labored at that. And it wasn’t a good idea to do that, because it took me forever to write a screenplay, and that’s why they called me “Happen Faster” instead of Hampton Fancher, I guess. And it hurt. I could have probably had a much more successful career if I had been writing quicker, as they do. I mean screenplays are all about, “Hey, that’s just a diagram. Get it down, and let’s shoot it.” But I wanted, you know, every line to be [James] Joyce-ian, or something. And I thought in the beginning it helped me actually, because it stood out. I thought that I was like an A-list writer.

On optioning Burroughs, Bukowski, and Dick:

In ’75, when I was looking for something to do. It’s the only time in my life that I’d ever have 10 grand in my life, I figured. Someone gave it to me, and they said, “Do something,” you know, in terms of option a property, or something. And so I decided to option three properties. I was totally naive. I didn’t understand how to do that. I didn’t know how much money it took, but I thought $10,000 is like $10 million. I thought I was Donald Trump. You know, I was like, “I own the world! I’ll do all this now!” I wouldn’t want to write and direct these things. I just thought they were good ideas commercially. Because I love these guys, I thought, “Okay,” which was dumb idea, especially in ’75, “William Burroughs.” No one even knew who William Burroughs was in that world of Hollywood, but that’s what I thought. And the other one was Charles Bukowski. And Bukowski, nobody knew who that was, and in ’75 especially. And the other one was Philip K. Dick. So I tried to get those guys involved, and I thought they could write a screenplay for themselves, and I would produce it. I didn’t mean literally produce it, line produce it. But I would see that it was done, and I’d reap the financial rewards from it, which would allow me to do the stuff that nobody would do. But this shit that I was trying to do to do that, nobody would do. It was impossible, and none of it happened. Except that I met all these guys and had a good time with Burroughs and Dick and Bukowski.

Listen to the full interview here.