Rakontur’s stories of shady people in sunny places

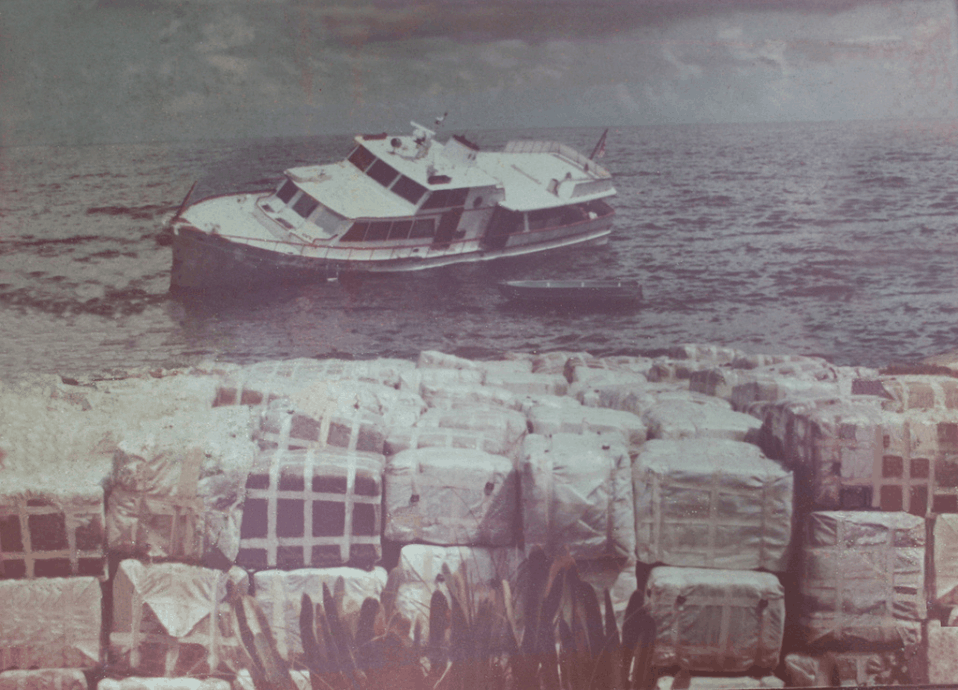

Presidential Yacht and pot bales

The opening shot finds the camera slowly moving across a sleepy seaside marina, stopping on a pile of square burlap sacks of marijuana. Cut to waves on a beach, pushing one of those sacks up onto the sand. Next, a shot of Miami’s downtown skyline, then a pan-down to more sacks laying on the grassy shore of a nearby island. Similar shots follow, with sacks in a sandy mangrove, a shining stone seawall, ocean-side picnic grounds, floating around an estuary, before finishing on a shot of the film title (built of burlap letters, of course) sitting on a sunset-kissed beachscape.

Overlaying all of this is the southern country-style singing of Raiford Starke, telling the story of the benefits of Florida’s maritime marijuana trade for the fishermen involved. The song is “Square Grouper,” with music and lyrics by the film’s director, Billy Corben:

SQUARE GROUPER

When the camera pulls out from the burlap title letters, it’s revealed that the scene is actually a paper photograph set inside a book-style album. The page is then turned to reveal the first picture-style shot of the film’s opening part, dealing with the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church. The economic clout that the sect achieved in Jamaica is the topic of a vintage TV news report that Corben intercuts with his own interviews with Coptics, including Brother Butch and Brother Gary.

Coptic Church in Jamaica.

Brother Gary and Keith Gordon

Black Tuna Gang fishing group.

We’re talking less than 500 people, and what eventually happened was 80% of the male population was arrested for marijuana smuggling.

Population, steady around 500 for the last several decades, and five family names in the entire town. And it is a fishing village literally in the middle of nowhere. They call it “the last frontier,” and anything that they could do on the water or bring in on the water, that’s what they would do. And that means poaching, ostrich plumes, Chinese immigrants, gator hides and eventually they kind of made their way to fishing, stone crabbing. They had a line on the river where they have all the fish houses. And what happened was [U.S. President Harry] Truman came in and dedicated Everglades National Park, and the waters became protected, and progressively more and more restrictions were placed on fishing in that area. This is the way the natives tell it. I’ll put it to you that way, and it’s historically accurate, but it also to a certain extent is a justification for why this happened. Commercial fishing was being squeezed out of the national park, and that was essentially the legitimate lifehood of the vast majority, if not the totality, of Everglades City and Chuckaluskee — with the minimal amount of tourism coming in, and airboat rides, and fishing trips, and charters and that sort of thing. But mostly, it was the commercial fishing. And the licenses that did exist, that were “grandfathered” in, but with an expiration date (that was the fine print), they were expiring progressively. The Mark Hunter story about it when he was working down in the Miami market in that time, he said that the federal government essentially told the citizens of Everglades City to find some other way to make a living — and they did. They had their boats. They had their marine charts and maps. And they made good use of them, and started to head on down to Colombia and Jamaica and meet mother ships off the coast, and started pot haulin’. And these are God-fearing church-going people. Many of them would whoop their kids behinds if they caught them smoking pot.

But then it turned into like the Beverly Hillbillies, because the next thing you know, all these folks have got money. There was one funny story about a wife who got so excited that she called into the city and had trucks come and deliver all new furniture for her house (new beds, new couches, new chairs, new dining room set, the works), and it got there, and there was no room in the house for all the furniture she had ordered. Her house was so small. They literally, after they had moved all the old furniture out, could not put all the furniture in. So, what did they do? They built additions to their houses. They bought the red wagons, which were very popular at the time. They had gold chains. It sort of transformed this little town. We’re talking less than 500 people, and what eventually happened was 80% of the male population was arrested for marijuana smuggling. There was two or three major raids: Operation Everglades, Operation Everglades II was like ’83-’84, and then ’89 I think was called Operation Peacekeeper. It was really over that span of time and, mind you, there were minor busts that occurred before that and in between those events. Those were the three major busts, but the first one, Operation Everglades, was the most famous.

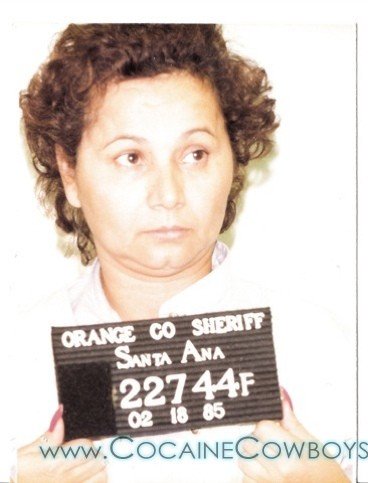

Famous, yes. But relatively harmless. Too much furniture and expensive house additions are not the collateral damage of Rakontur storytelling’s most darkly compelling villain. Murder victims and a closet full of high fashion accessories (both considered easily-disposable) were more to the liking of one Griselda Blanco, aka “La Madrina”, aka “The Black Widow”, aka “The female Tony Montana.”

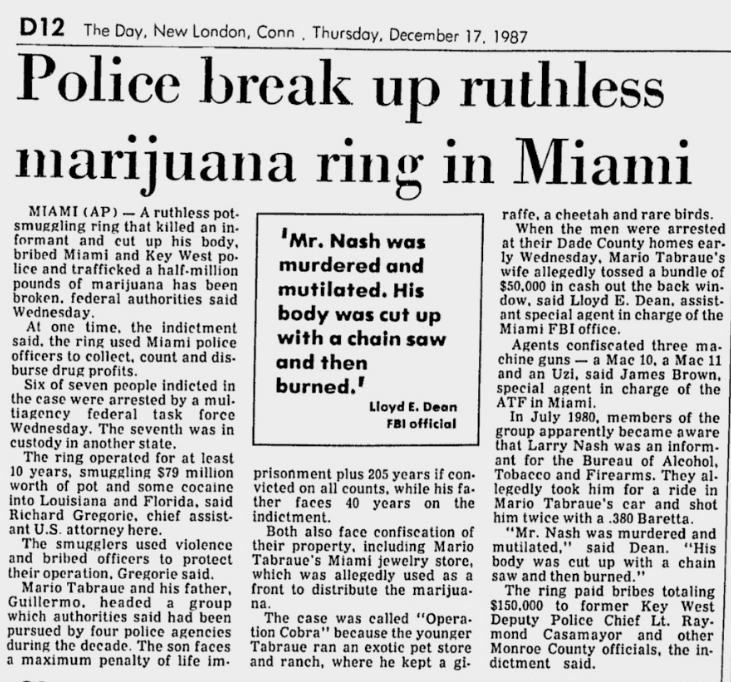

Square Grouper article, December 1987

He’s terribly charming and disarming, and the way I tell it is that he also speaks in a very soft voice. So, when you’re interviewing him in prison, you have to lean in close to him so you can get his mouth closer to your ear. And it’s about that moment that you realize, “Oh, I could be dead right now very easily,” and you understand why he was good at what he did. You have to remind yourself in that moment, “Holy shit, this is a guy who killed women and children and men with impunity if the price is right, or if there was a price that his boss put on their heads, and wouldn’t think twice about it.” So, he was very chilling and effective in that way — the way he put you at ease actually in his presence. I mean, we realized the movie was kind of a three-act structure in terms of the subject matter: drugs, money and murder. That was the story. It was the drugs, the money that came from it, and then the necessity of having to enforce a trade that generated that kind of money, because it’s a consignment business. You give someone two kilos, three kilos. You come back next week, you say, “Where’s my 150 grand or 200 grand?” And if they don’t have it, it’s not like you take them to court. You have to enforce your trade off the books, if you will, and they did that with enforcers and hitmen like Rivi. And so, we knew we had to get somebody from that role. Rivi is in a very unique situation, because he had a plea bargain with the state attorney in Miami-Dade county where he could speak chapter and verse on all of his murders and crimes that he committed in Miami-Dade county without fear of the death penalty. He essentially pled to three life sentences in exchange for his cooperation, and to avoid the electric chair at the time. We don’t use the electric chair any more — “Old Sparky” as it’s called down here. In fact, [Producer] Alfred [Spellman] corresponded with other hitmen who worked for Griselda Blanco (“La Madrina”), including Miguel Perez, who was the Marielito who committed the attempted murder on Papo Mejia at Miami International Airport with the World War II bayonet, where he stabbed him like six times and the guy survived. Miguel Perez, we met him in prison, and went so far as to set up the equipment for an interview he agreed to. And then, he was escorted by the prison guard to the set, and he said, “I can’t do it. My lawyer says I shouldn’t do it.”

Then there was Cumbamba, who you might recall earlier in the move, he helps with the [Herman] Grenados murder. This was the murder that Rivi had fucked up at the Jacaranda nightclub. That was the first time he met Griselda, who said, “Well, you’ve got to help us find him.” Rivi didn’t do this hit. But he helped them locate Grenados by paging a guy who knew him, or whatever. And he came, and that’s the guy whose blood they drained in the bathtub, and then broke his bones, so they could fold him up and put him in that box alongside the highway that we had the crime scene photos for. So Cumbamba, the guy who was involved in that hit, Alfred wrote him in prison. He was in prison in Louisiana for the murder of Barry Seal, the CIA operative turned drug informant who was murdered by Colombian hitmen in Baton Rouge at a halfway house.

Griselda Blanco’s mug shot

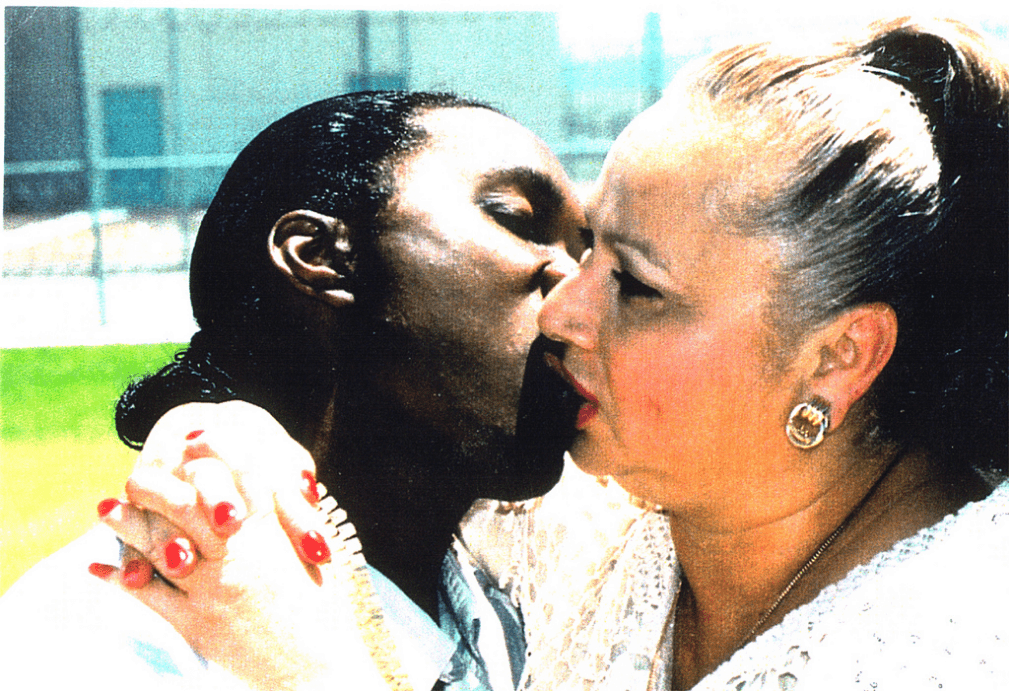

Eventually, Blanco turned on her benefactors, fleeing South Florida before being captured by law enforcement in California, and ending up in federal prison. Even locked up, though, her aura as the very rare woman to rise high in the cocaine trade (allegedly still earning $50 million a year behind bars) attracted a handwritten letter of admiration from Oakland, California-based crack dealer Charles Cosby. Intrigued, Blanco responded, and a phone correspondence was started, which then evolved into both a business and romantic relationship. In the early/mid 1990s, Cosby ran the cross-country cocaine operation of “the Black Widow” (after her three dead husbands), becoming Blanco’s lover (also taking a bullet for straying), getting entwined in a bizarrely ambitious prison-break plan involving the kidnap and ransom of John F. Kennedy Jr., and a sex scandal in the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s office that led to Blanco’s unexpected early release and deportation back to Colombia in 2004 — all chronicled in Cocaine Cowboys 2.

Griselda Blanco and Charles Cosby

Sal Magluta, Willy Falcon

Flamboyant dope boy, I’m talkin’ Al Capone

My Mexicano not talking tacos