From the book of poems Death Of Art

Anything over one is it

Self made ready

Ready made

The world just by

Close your eyes

Is that a thing

Mid-century music

Pole dancers drag

Race the street

I grew up on

Teenage mutant

Turtles I never had

A friend till I was

Five I learned to read

A year later & loved

Everyone I met

Becoming like bodies

In a bathtub

Wet all the way up

To my lips

To say When

I told you like remembering

The taste of your first

Mango my

Safe word

Add some more

Or tell me

When again

I can let the water run

All the way sounds

The same as silence

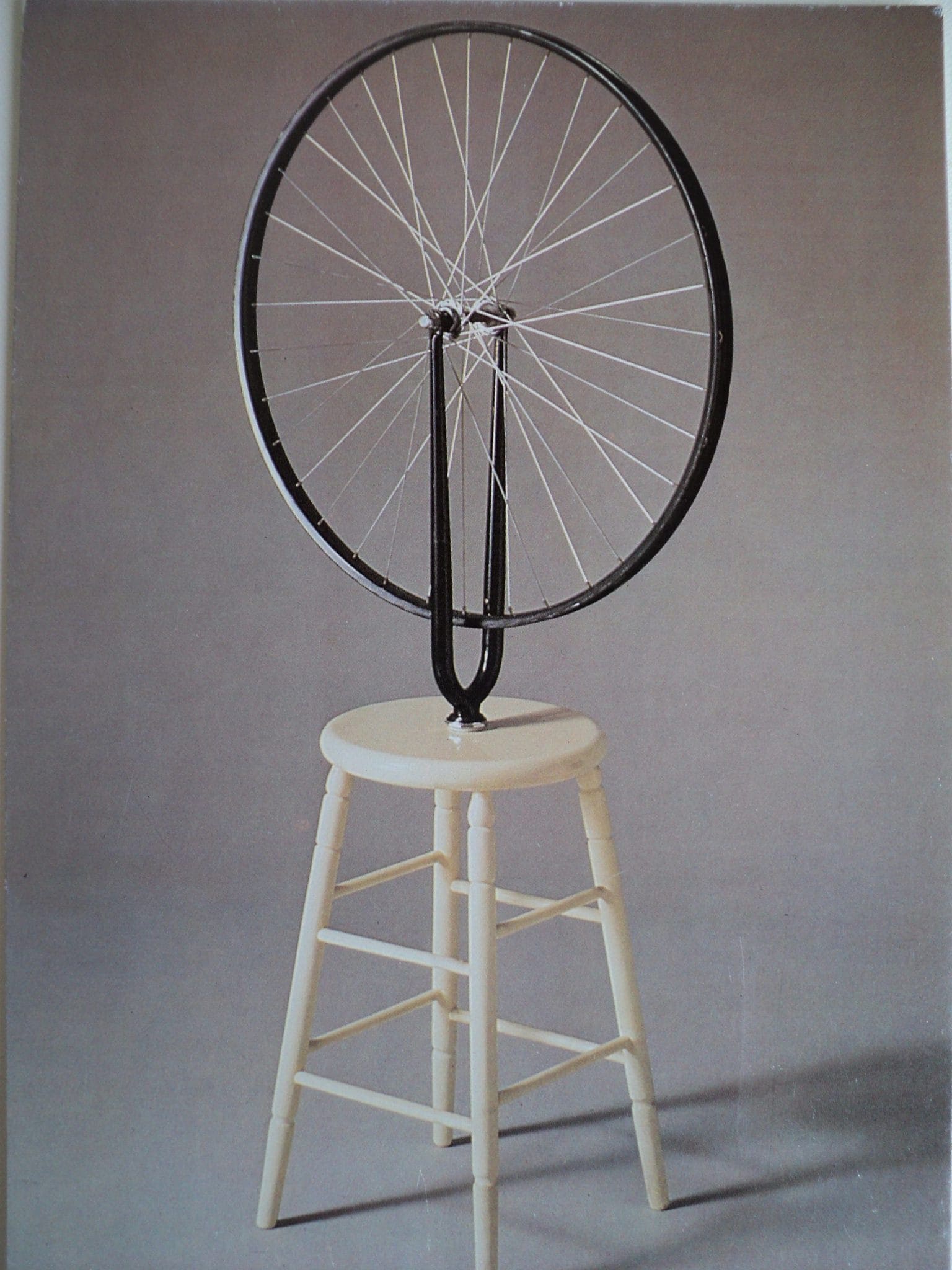

Bicycle Wheel by Marcel Duchamp. New York, 1951 (third version, after lost original of 1913). Metal wheel mounted on painted wood stool.

Context in offering to the poem Anything Over One Is It

Our concept of authenticity, or at least being true to ourselves, has always relied on recognizing social rules and norms and the scripts we are asked—or forced—to perform because of them. If we recognize what we’ve been culturally conditioned to think or do, we put ourselves in a position where we can re-write the script. But what happens when those revisions, too, are always already made for us, updated and autocorrected? The concept of the ready-made found “new” life in Marcel Duchamp’s manufactured objects; by simply choosing the object and repositioning it, titling it, and signing his name, the found object became art. It was only a matter of looking; to be held and behold. Today, the found object has been given an almost-limitless panorama in which to be hailed, re-situated, and signed (in) via the World Wide Web. A click of the mouse or a finger on a touch screen has manufactured convenience and replaceability, a concept of newness that has been fed and upended through its very reproduction. When objects and people move that fast, it doesn’t look like we are moving at all. The concept of the always-already ready-made has also made identity just another prefab, gossamer construction, less sleight of hand than smoke and mirrors: the camera pulls back in a mise en scène to reveal that nothing else actually exists beyond the beautiful binding.

In an age in which it is so easy to be misrepresented—or misrepresent yourself—on the Internet, “to be known” might be the mode de vie of our culture. The utopic possibilities that exist on a blank page, and the communion and connection that writing and reading allow us, have never been more important and more ignored. We grasp outside of ourselves by being able to imagine other worlds and all the perspectives that live there, beyond our own. I think that’s one of the greatest things about poetry; we can overcome this distance in a single line or a single word that breaks one line from the next. The tension that exists within that threshold is our striving for intimacy, as evidenced by the primal, sexual undercurrents of this poem’s finale, particularly the charge in each succeeding line as it is lineated, splintered, and re-done.

I’m not good at math and have never been comfortable dealing with numbers, but I treasure fractions, fragmentary syntax and thought, the half-heard echo or call heard in pieces that resonates even as it ruptures. The traces of that transition—what came before, where we are always already going—is a liminal experience that intensifies all others, one of the reasons why our image-rich culture is especially captivated by gifs, pictures half-frozen between an arrested movement and the pose of permanence. The best of both worlds in a finite existence.

Sometimes it’s best to close your eyes.

Chris Campanioni

Brooklyn, April 19, 2016

Click here to preorder Chris Campanioni’s book of poetry, Death Of Art, published by C&R Press.