Documenting Bushwick’s Many Passages through Poetry

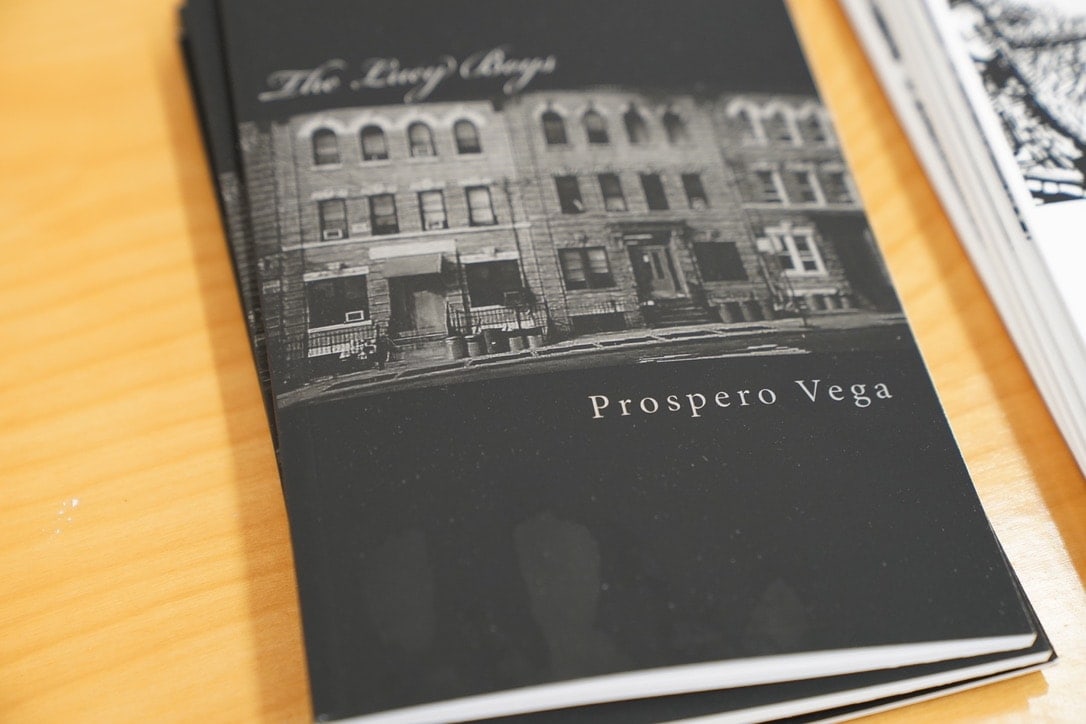

The launch of Prospero Vega’s “The Lucy Boys”

Who better to write about a gentrifying neighborhood that’s losing its previous identity than a native who enjoyed everything both sublime and depraved about that identity? That’s the sometimes-exhilarating always-engrossing hook for “The Lucy Boys,” a new book of narrative poetry and documentarian photography from Prospero Vega.

A good example of that hook is the first stanza of A Mush is not a Push:

Getting a blow job from

your local biker gang drug dealer

at a cucaracha-infested Bushwick basement at 6a.m.

cause there is nowhere else to go,

then being told that doesn’t make you square with him

for the money you owe is well, personal shit

Vega grew up in Bushwick during the decades before its current incarnation as a Mecca for creatives — back when drunks and drug addicts were neighbors and friends who painted or sculpted or performed in relative obscurity. Vega takes that experience and starkly contrasts it with his view of Manhattan’s young-moneyed artist set within the first half of The Lucy Boys‘ title piece:

i’ve been seeing rich kids falling asleep

in nice neighborhoods

like the West Village,

and Midtown West,

the nicer parts of

Chelsea, on the street

and even by

where i work on

the Upper East Side.

just passed the fuck out on the sidewalk.

these aren’t the drugged out

mural artist wannabes i get

in Brooklyn or The Bronx,

who drink as if

drinking might make them

INTERESTING.

unknown, untalented but not uncaring.

they care very much to be famous.

you can tell these were nice kids

who once got all the girls,

drove all the cars,

but they are artists now.

don’t believe me? ask them.

“i am an artist”… they will say.

trust me they are not painting.

these guys in suits,

people wearing

name brand sneakers,

clean shaven.

i’m not sure i like this.

this new rich homeless person fashion style they got going

on.

Here, Vega brings things back home to Bushwick, using the wardrobes of these wealthy wannabe artists to explain the book’s title:

They look like the Lucy Boys we used to pay a dollar to, to

go get a Newport or a Marlboro across the street from after

hours joints like “Luisin’s” in Bushwick when were running

low on funds

these professional down-and-out types

you almost want to

stop and wake them up.

Slumber also styles Vega’s bigger picture of Bushwick’s tapestry of citizens, who inspire The Lucy Boys’ most affecting poetry about the neighborhood — starting with the dream-like flow of the book’s opening poem, The Nighthawk:

i once had

an idea for

~a film~

that started with

people sleeping.

everyone was in a kind

of collective coma

in Bushwick.

they looked dead.

Barbers

sleeping.

Supermarket bag-boys

sleeping.

Police

Sleeping.

Domino-players,

bottom-dollar dreamers

sleepers, sleepers, sleepers.

Dallas Athent, who has long had her eyes open to Vega’s talent, published The Lucy Boys via her Catopolis imprint. I reached out to Athent while working on this review, and she described Vega’s particular appeal:

I’ve been Prospero’s biggest fan since I first read his submission years ago to the short story collection, Bushwick Nightz. I find his work honest, raw and also, hilarious. His point of view about growing up in Bushwick in the ‘90s isn’t sugarcoated, and I think that’s a story that needs to be told.

Aiding that story are black & white photos at the top of each poem, portraying Vega’s sidewalk views of Bushwick — including long lines of derelict freight train gravel carriers, a burned out car in an overgrown lot, a line-up of beautiful brownstone facades, and an old torn-up mattress leaning against a corner shop entrance that locals pass by. It’s an aspect of the book that Athent considers essential:

The photos were all taken in Bushwick in the early 2000s with a disposable camera and the stories take place around the same time, although Prospero wrote them years later in the 2010s. The fact that he wrote them at a different time in his life adds to the reflective quality about them, and also their ability to transcend time and not feel “of the moment.” I love the dreamy aspect he adds to work that’s about hard topics.

And there are plenty of difficult life details in The Lucy Boys that read as confessions of debilitating addiction ripped from Vega’s diary — multiple entries of which make for poem titles, including this opening excerpt from Diary #32:

Where do I start to do something anymore?

In a forest? In a cabin?

In a bathroom stall doing meth in Hell’s Kitchen (yes you

can still get away with that in Hell’s Kitchen if you know

where to go afterhours) while “Darkness At The Edge of

Town” blares in the background for the 5th time on the

jukebox?

Yet, Vega also makes time to understand those who deal out the drugs that haunt his poetry — as in the opening stanzas of Circles:

I was sitting with local legend and drug dealer, Ivan Muñoz

who always went by his last name “Muñoz”. He was lying

in his bed, dying in the Borinquen Plaza houses ebbing in

and out of inner monologues and flash cuts. His fifth wife

was with us, whom he allowed to fleece him pretty dry.

Ivan had owned a couple of notorious night spots in the

70s and 80s back when he would donate to the annual

Policemen’s ball, but now he was working hard to die in

bed, still tearing people up with wild stories of his time as

an infantryman in Korea.

On January 27th, Vega read his work for an audience at Catopolis’ joint release party for The Lucy Boys and Ronna Lebo’s new book of poetry, Hell, Probably. The event took place at MANA Contemporary in Jersey City — two rivers removed from Bushwick, from which Vega himself has now moved away from. Reading the 22 pages of The Lucy Boys, though, will take you to the past and the present in an ever-changing Brooklyn.