Night-4 Hour-1

Abrahams: “You cannot fault Shaka’s deductive reasoning: Christ to heaven, heaven to Zulus, Zulus to Shaka. I wouldn’t be surprised if someday Christ were wedged snugly into Zulu genealogy. That seems to be the curious legacy of Jesus: to be adopted by others.”

— Zacharias Abrahams explains Shaka’s belief that he is heir to the power of Jesus Christ. From hour seven of Shaka Zulu.

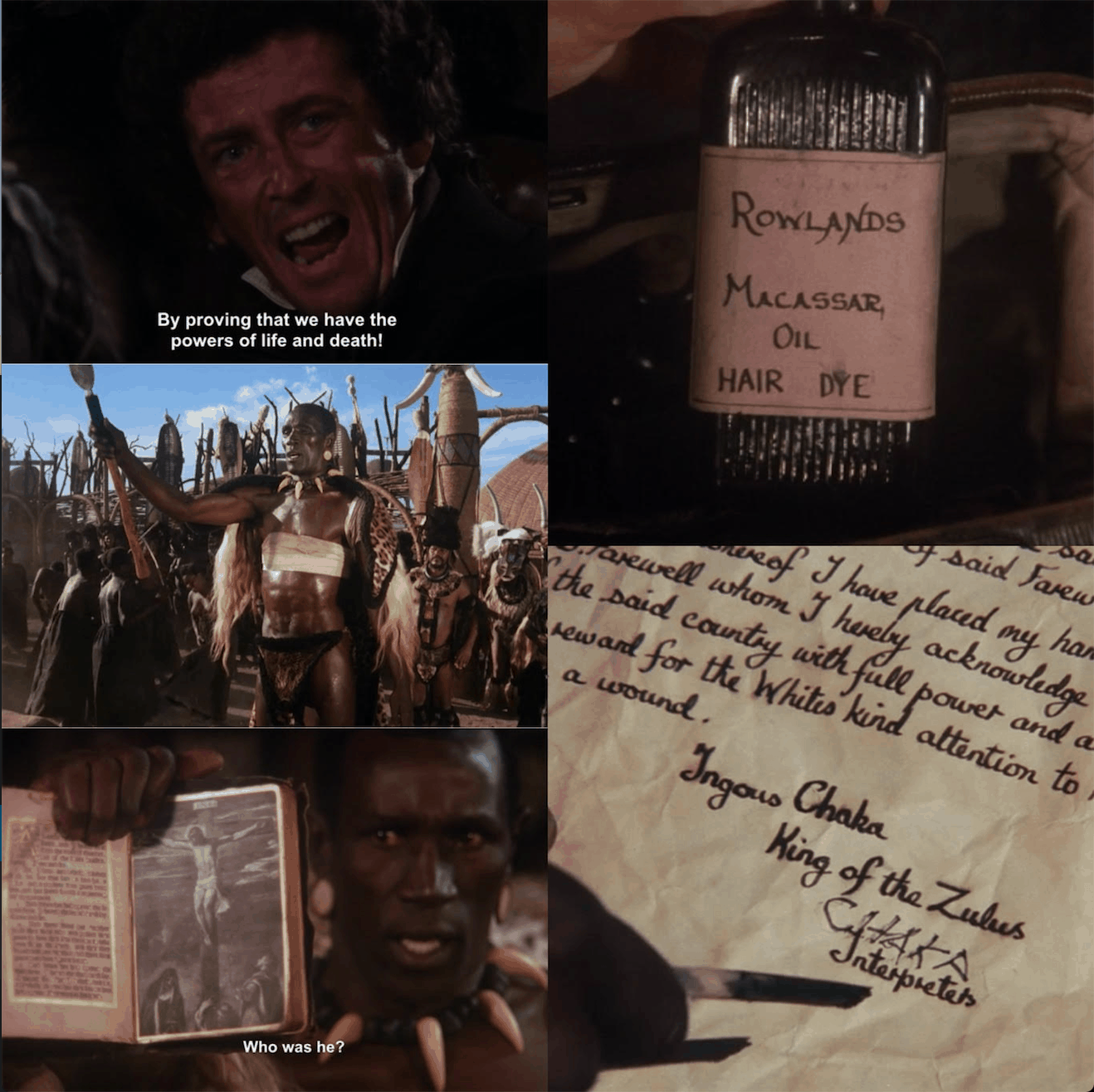

Gore and partial nudity were visceral elements that set Shaka Zulu apart from other U.S. network-aired miniseries events. But another edgy recurring theme viewers saw over five nights of prime time TV was the Christianity-fueled idea of entering into a “devil’s bargain,” like the one that Faust cut with Mephistopheles. Tonight, Shaka himself signs his name to such a contract, writing the letters for “Chaka” taught to him by interpreter Piet Vegte on night one. The paperwork is crafted by Lt. Francis Farewell, who tells Dr. Henry Fynn, “We control Shaka’s soul, we control the whole of Southern Africa.” Yet, unlike Faust, the Zulu king is fully confident he can nullify his bargain at any moment, and murder the devilish Swallows to whom he has gifted wealth for saving his life. Moreover, he views himself as the heir to the Christian devil’s greatest adversary: Jesus Christ.

That belief comes thanks to a theological conversation with Fynn, played by Robert Powell — whose most-memorable acting role is starring in 1977 BBC miniseries, Jesus of Nazareth, directed by Franco Zeffirelli. Thanks to clever casting (intentional or not), Shaka Zulu essentially asks “Jesus” to defend his own importance to a pagan king who accidentally discovers a picture of the crucifixion in Fynn’s bible, and demands an explanation:

Fynn: “That is the King of Kings. That’s Christ.”

Shaka: “Was Christ greater than Georgie?”

Fynn: “He’s greater than George. He’s greater… than Shaka.”

Shaka: “His death, hanging from a tree near weeping old women, is not worthy of a king.”

Fynn: “No, it’s not.”

Shaka: “How did he come to die?”

Fynn: “He was… he was betrayed… by those that he loved the most.”

Shaka: “Yes… It is a mistake to love. Especially for a king.”

Indeed, the fourth night of Shaka Zulu begins with the betrayal of the king, orchestrated by his duplicitous half-brother, Dingane. The assassination attempt occurs in February 1824, at the height of one of the miniseries’ stompingly-stunning tribal song/dance sequences, with Shaka at the center of a swirling mass of celebrating Zulus. The hit is carried out by a warrior of enemy king Zwide, disguised as one of Shaka’s ufaSimba bodyguards. The failed assassin is quickly killed by Dingane — whose treachery is recognized by Mkabi, and suspected by Zulu general Mgobozi.

In the aftermath, Dingane dodges public blame, but punishment is severe for several others. Shaka eventually orders 10 ufaSimba to be impaled alive for failing to recognize the masquerader in their midst. The Swallows will certainly suffer that fate if Shaka does not survive a spear-punctured lung. So, it falls to Fynn to treat Shaka’s wound as best he can. Miraculously, the king recovers enough to stand in front of the assembled tribe, raise up his iklwa, and preserve his ruling power.

The appearance of power over life and death now elevates the Swallows to tenuous authority figures. The risk/reward approach they take, though, is derived from Farewell’s decision to apply some of Fynn’s small supply of macassar hair dye to Shaka’s scalp (“an added touch for show”), before helping the king shuffle out to his reign-saving public display. Shaka takes the effect to be a heavenly rejuvenation, and orders the same treatment for his aging mother, Nandi. Despite the limited supply of hair dye, by November 1824 Farewell has exploited the king’s gratitude into a contract-sealed reward of seaside land for British-owned Port Natal, and the rights to hunt the surrounding territory for valuable elephant ivory to supply The Farewell Trading Company. However, even as the Swallows bundle tusks in their meager wooden fort, all are aware of the uselessness of such wealth to the impaled men they will be when the illusion of Shaka and Nandi’s new “youth” is discovered.

This hour’s crucial Christ discussion sprang from the mind of Shaka Zulu writer, Joshua Sinclair. Utilizing the convenient presence of Jewish Swallow, Zacharias Abrahams, Sinclair frames the exchange as an unexpected prime time network television debate on Jesus’ divinity. Shaka and his isangoma Sitayi pose doubtful questions to Fynn, while the camera repeatedly cuts back to a quietly smiling Abrahams as a Jewish representative all too familiar with their doubts — a sympathetic dynamic that Fynn comments on:

Fynn: “Well, whether my friend Zacharias or you know it or not, Christ is the lord of the Whites. He is the lord of the Zulus. He is the lord of all men. He is the son of the heavens.”

Shaka: “Do you derive your powers from him?”

Fynn: “He is power. With Christ in your heart, you’re stronger than all the regiments on earth.”

Sitayi: “If Christ is power, why did he not save himself?”

The isangoma’s question hangs in the air, with Fynn visibly reluctant to answer, before Shaka fills the silence with his own interpretation:

Shaka: “Christ had to die, so that the heavens would pass that power on to me. The youth they have given me is proof that I have inherited that power. Heavens belong to Zulu, and Shaka is their son. If the Swallows wish to be my friends, they must remember that. In this land, there is only one nkosi yamakhosi, only one King of Kings… Shaka.”

Sinclair explained that mindset during our 2013 interview for my film site, Camera In The Sun:

For me, Shaka’s greatest curiosity was “[Whites] come from all the way over there. Why? What are they doing here? What do they want from me? They want me to believe in this king who died on a cross, betrayed by his own disciples — who were, for the most part, unarmed? No army was there to help him? Nobody? They just killed him? And that king is now the most powerful king in Europe? How? I’m a ruler. I’m a general. I’m the head of an army. They call me the ‘nkosi yamakhosi’, ‘the king of kings.’ Why is that king of kings better than I am? Why do they want me to believe in that king of kings? What is it about him?” Well, the secret of that king of kings is forgiveness. Because you throw a rock, they throw a rock. They throw a rock, you throw a rock. And it goes on forever. The idea of truth has to come from forgiveness at some stage. Somebody has to say, “Enough.” As many people said, including Gandhi, “To reach out and shake the hand of a friend is easy. But to shake the hand of an enemy is almost impossible. But until you do that, you can’t find peace.”

However, Sinclair readily admits that he invented such ethical explorations to fill in the blanks of Shaka’s biography, while altering other characters he met for dramatic effect:

When I wrote the script, 70% of it I made up. But I didn’t make it up myself. I got it from people. I lived with the Zulus. I heard the Zulus. I listened to them. I threw stuff in myself. Shaka had never heard about Christ. The first missionary to the Zulus was Reverend George Champion, who went to Dingane, who was the half-brother who killed Shaka. But Shaka himself had never heard about Christ. Henry Francis Fynn was not a doctor. He was Superintendent of Cargo. He didn’t know Christ from a hole in the head. Yes, he was an Irish Catholic. But I turned that into a big thing. Francis George Farewell was more or less the same as Farewell was. Although, I turned him into another sort of figure. So Fynn existed, but didn’t exist the way he did in my script. So I said, “As long as he’s Irish, and as long as he maybe is sort of a missionary and has a theological background, let’s get him involved.” I wanted to confront the “king of kings” who has a standing army of one million, with the “king of kings” that the Brits keep talking about — who died on a cross with nobody around, except a couple of women and an 18 year-old kid. This absurdity of our Christianity, of the entire Judeo-Christian origin of our civilization, is for a Zulu something which is very difficult to understand. That’s why I have at the end of Shaka, especially in the book, that he can’t understand who this man Jesus is that they keep talking about. I needed to bring that in — which he didn’t know about, but I needed to understand. Shaka was a very curious man. He had to be curious, because he created this incredible empire. He asked, “Is this the right weapon?” Then he invented the iklwa.

With his body seemingly rejuvenated, and his status as violent heir to the peaceful Jesus in mind, Shaka will now take up his iklwa once more to lead the Zulu army in a war of vengeance against Zwide — with the explosive “powers” of the Swallows set to play a decisively deadly role.