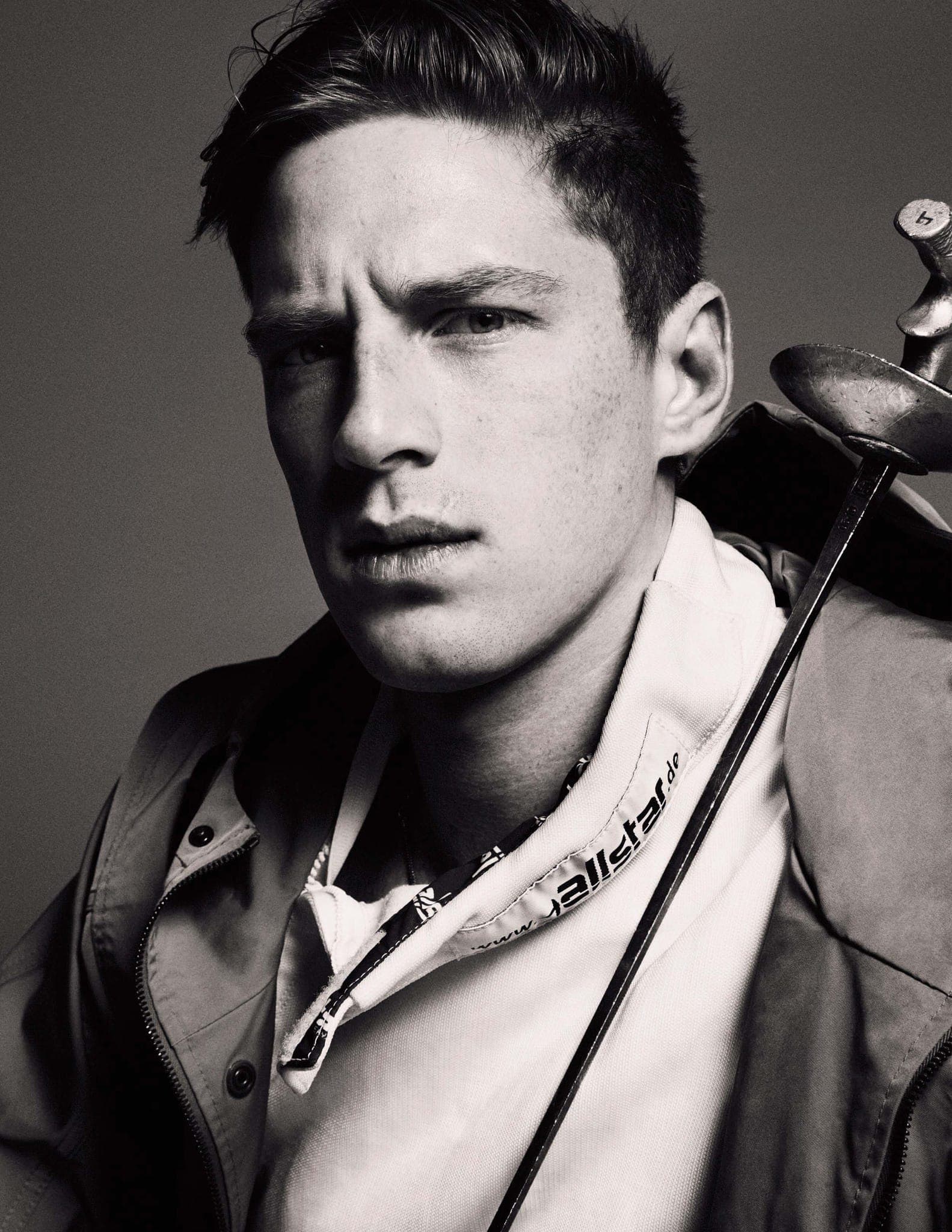

LOOK

SHARP

RACE IMBODEN TAKES A STAB AT OLYMPIC GOLD

Written by Joseph Bullmore

Photography by Bjorn Iooss

Styled by Matthew Marden

Jacket TOMAS MAIER

If any publicists at the International Olympic Committee are reading this, I’ve got the billboard thought for fencing wrapped up: “The tip of a fencing foil is the second fastest thing in sport. The fastest is a bullet.” And though those words read like flourishes in a Madison Avenue copybook, they actually belong to Race Imboden, fencing’s twenty-three-year-old golden boy.

In this case, the style fits the substance. Imboden—and you’ll know this when you watch him on television, which you will—stands at the center of a Venn diagram that comprises (with apologies to the French Republic) ability, publicity, and New York City.

That curious constitution of athlete, model, and Brooklynite makes Imboden something of a poster boy for what, until very recently, was a sport distinctly absent from the American playbook. And if you’re scratching your head in wonder that a game in which men attack each other with blades is struggling for stateside coverage, Imboden has a couple of theories.

“They should call it sword fighting, really. The title just doesn’t do it justice.” He should know, all right. When, as a young boy on an Atlanta playground, he began hitting his friend over the head with a plastic lightsaber, he wasn’t fencing, of course. He was sword fighting. But someone with a better-trained eye begged to differ.

“This other parent came up to me and said, ‘You should try fencing.’ I had never even heard of it, but I asked my parents if I could do it.” What happened next reads like a movie treatment for a sporting epic (are you with us, IOC?). Imboden’s parents—like gloriously demented soccer moms—drove for three hours to the nearest fencing instructor. But when the Soviet-bloc exile stepped out of the building (“The man was born without a neck,” notes Imboden, always quick with a bit of color), he took one look at the lithe little boy and said, “Too young,” before careering back inside.

That long ride home would have blunted most eight-year-olds’ ambitions, but it galvanized young Imboden. Circling the required date in red on his Seven Samurai calendar (that’s my poetic license), he began to devour the fencer’s reading list, his elbows pinning down the pages. Can you hear the montage music? When the day came for him to return to his dojo, he didn’t just float: he swam. And if Lady Luck was in the stands in Atlanta, then she was in the coaching booth in New York. When the family arrived in Brooklyn, they discovered that the best fencing club for miles around was just a block from their front door. Destiny doesn’t quite cut it.

The sense of theater here isn’t utterly frivolous, I promise. I don’t have to bring up Hamlet, or Tybalt and Mercutio, or the very fact that the first use of the word fence is found in The Merry Wives of Windsor, to tell you that the sport has always lent itself neatly to storytelling. It’s no coincidence, either, that fencing’s saunter from deathly pursuit to organized sport was pegged directly to that of another creative outburst, the Renaissance. In the eighteenth century, meanwhile, the French and Italian schools of fencing were outpacing all others just when their literature was blunting all newcomers. And then there’s the pure ballet of the thing: the masked, white-clad figurines; the French nomenclature; the marriage of youth and classics; the poise and pose.

Imboden isn’t afraid of a bit of pantomime himself. “Oh, I let them know,” he says, referring to his wild, hollering celebrations, not to mention the requisite chess-like mind games. On the strip, of course, “one man goes home, and one man goes on.” Off it, however, things are as cordial as you’d hope: murderers sharing drinks in the wings.

It was in one of these unguarded moments, in fact, that Imboden’s other calling came to the fore. Spotted, unmasked, by a New York modeling agency during a TV appearance, the fencer soon found himself wearing armor of a different sort entirely. The catwalk, after all, is about the same diameter as the fencing strip. “I have these nightmares of duck walking down the runway,” he says, referring to the splayed-foot stance of the master fencer, “but, at all times, I’m much less nervous going out there than stepping out onto the strip.”

Well, those priorities seem about right. This summer, Imboden will travel to Rio de Janeiro as America’s first realistic stab at a fencing gold. “If you’re not feeling the pressure, you’re not doing it right,” he says, when I ask him if the prospect hangs heavy around his neck. There is a sense—now more than ever—that something is moving, unseen, offstage. Team America knows full well that Imboden—arm in arm with his three brotherly teammates—could usher in fencing’s watershed moment.

“Nobody walks away from a fencing match and says, ‘That was pretty dull.’ Nobody,” he says, breezily pitching me his idea for a future professional fencing league. “It’s the closest thing we have to gladiators today.” Well, what’s that phrase about bread and circuses? After Usain Bolt walked to an Olympic gold, the enrollment rate in youth athletics shot up like a starter’s pistol. The same was true of rowing on the morning after Steve Redgrave’s eighth medal at Sydney. And soon, perhaps, when those parents ask their children just what is it that they’re doing with that cane, or that branch, or that umbrella, they won’t say, “I’m sword fighting.” They’ll say, “I’m fencing.”