The

Beach

Boy

The Sustainable Style Of Harry Gesner

Written by John Horn

Photography by John Balsom

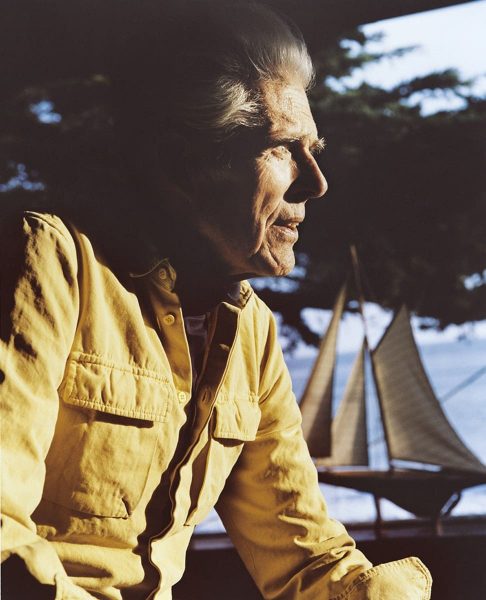

The architect Harry Gesner has spent most of his adult life either near or in the Pacific Ocean, and when you spend as much time as he has watching the waves roll up to the foundations of so many Malibu mansions, you start to understand the waters better than most.

About ten years ago, the architect, who is now ninety, was atop one of his prized longboards—he is fondest of Velzy and Jacobs balsa-wood designs from the 1950s—when he spotted two dolphins approaching. “I could talk to them, in a way, by tapping on the top of the board,” Gesner says, taking a break from his increasingly busy portfolio of residential commissions. “And they would respond to me, like friends. They know who I am and where I am better than I do.” Kneeling on his board and paddling just beyond the incoming series of breakers, Gesner saw the pair of aquatic mammals line up on either side of his board, so that he could touch the dolphins’ dorsal fins with each stroke, as if they were fighter pilots shepherding the lumbering bomber between them to safety. Gobsmacked by his close brush with nature, Gesner hurriedly surfed to shore, and asked a pair of his Malibu neighbors on their oceanfront deck if they had seen the close encounter. Looking up from their drinks, they told Gesner they hadn’t noticed a thing. “You’re a nut,” they said. “Would you like a martini?”

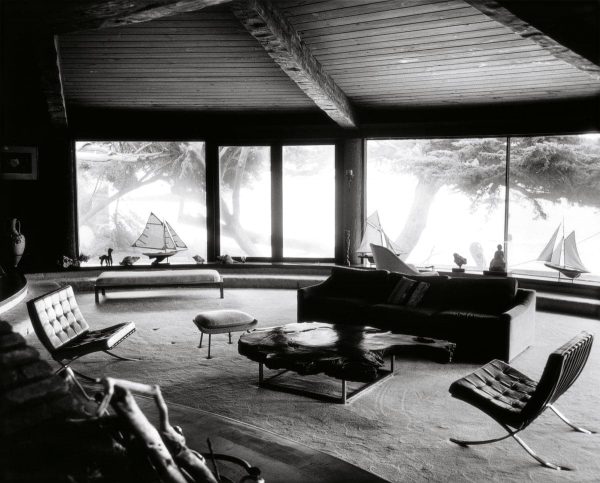

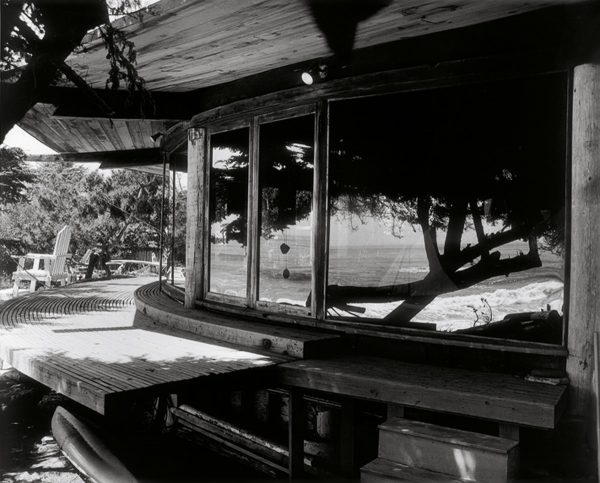

The living room of the Sandcastle.

The couple wasn’t the first—and certainly won’t be the last— to miss what Gesner alone sees. A true native of Southern California, Gesner has come to define a branch of muscular and elegant West Coast architecture through blueprints that not only integrate nature into design but also indulge the kind of ornamentation that inflexible modernists would consider apostasy: castles, ships, and stained glass are in lockstep with contemporary aesthetics. Gesner’s current focus is building habitable spaces that he calls “houses that survive.” While his intent is that the structures—which include tents and tree houses—outlast hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfires, earthquakes, termites, and even the demise of electricity and fossil fuels, they are just as likely to endure as testaments to a singular, self-taught vision that somehow is both influential and inimitable. And even as his knees have given out, forcing him to leave his surfboards in the garage, Gesner has never been more in demand. “I have a list of projects so long I’ve forgotten what most of them are.”

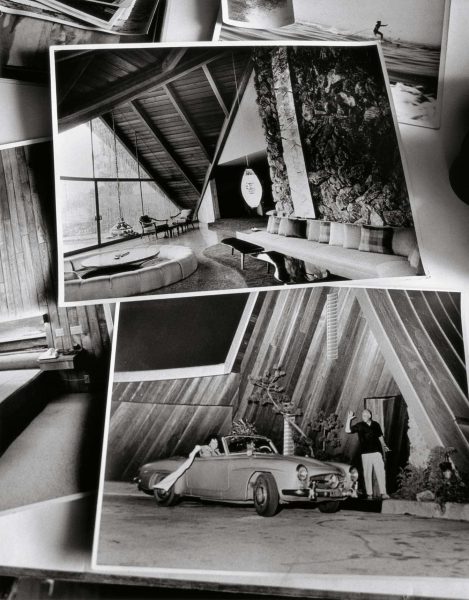

The Cole House in Hollywood Hills in the late fifties. The house was designed for Fred Cole, of Cole of California (swimsuit company).

Trailblazing talent surrounded Gesner well before birth. He is the great-great-grandson of José de la Guerra, a knight and Spanish capitan of Santa Barbara; his great-grandfather designed the repeating shotgun for Winchester Arms; and his uncle was Jack Northrop, the aircraft designer behind the stealth bomber prototype. Gesner survived Omaha Beach on D-Day, but nearly lost his legs near the war’s end to a German tank volley and subsequent frostbite. Gesner always recognized beauty and élan—one of his teenage girlfriends was actress June Lockhart—and when Gesner audited classes at Yale, Frank Lloyd Wright took note of his sketchbook. Wright urged Gesner to study under him at Taliesin West. “And I said, ‘I don’t want to be another you.’ So I gave myself ten years to teach myself, and study my own way. It took me five. I became a carpenter, a bricklayer, a plumber, and an electrician. I can build a house from scratch because I know all the trades. It gives you more breadth and scope as to what can be done with the tools and materials at hand. And that, in turn, gives me the inspiration to test the limits.”Most of my houses

Most of my houses are built on difficult sites.

I demand it, almost, that they find the most difficult situations —a mountain, a rock, a lake—and then design for it

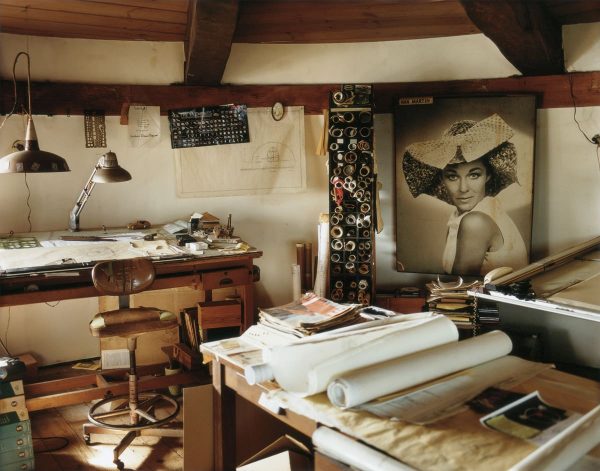

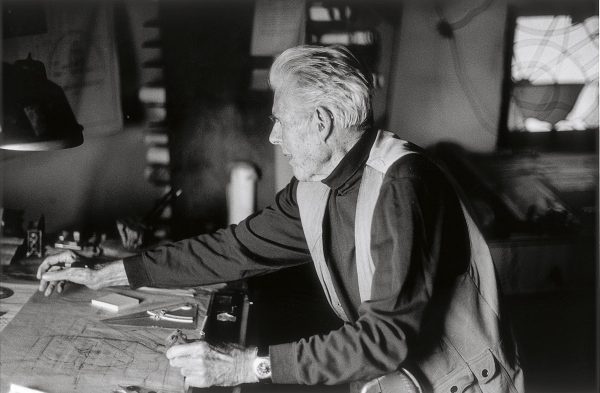

The Studio. At 90 years old, Harry still climbs a spiral driftwood staircase to get to the drawing.

While other buildings preceded it, Gesner’s architectural epiphany was 1957’s Wave House. That the Malibu home’s three enormous vaults look like giant waves about to crest is scarcely incidental. Gesner surveyed the site from every possible angle but only settled on its central conceit while looking at the lot of land from the sea; he sketched out the elevations with a grease pencil while on a surfboard, using its balsa deck as his drafting table. At once, the Wave House both mirrors the elements and welcomes them. “It was as if we lived within, not apart from, the forces of nature, and surged with her changing moods,” the home’s owner, Glenn Cooper Jans, said several years ago. With the Wave House, Gesner’s reputation was born. When the Danish architect Jørn Utzon laid out his plans for the Sydney Opera House a few years later, it was inescapable that Gesner’s genius had burrowed into Utzon’s dreams.

That the Wave House’s location was relatively suitable for construction proved, as Gesner’s later designs would illustrate, anomalous. Just as Yosemite rock climbers are drawn to absurdly vertiginous pitches, Gesner is most stimulated by sites wedged along canyons, clinging onto hillsides, or otherwise shoehorned into what many architects would immediately reject as unfit. Condor Crag, conceived for a cinematographer for Gunsmoke in the late 1950s, sits atop a tiny wedge, balancing on a clifftop half a dozen miles from Malibu. The Wing, built nearly two decades later for Gesner’s friend Mike Hynes, has a toehold on a small hill above Mulholland Drive as precarious and majestic as an eagle’s nest.

“I am especially concentrating on the environment—and working with the environment, rather than trying to change it. Most of my houses are built on difficult sites. I demand it, almost, that they find the most difficult situations—a mountain, a rock, a lake—and then design for it. So that it looks like it’s a part of that world. Why destroy nature? It’s the most beautiful thing we have, so why not work with it?”

The Sandcastle deck

You might say

my enthusiasm for life keeps me young. I am more creative now than I was in my earlier years

Working with the environment means that everything Gesner now takes on must be profoundly sustainable: he wants his homes to be off the grid (he continues to refine an electric car motor of his own creation) and to be made from renewable or repurposed materials. His own Sandcastle residence in Malibu, built in 1970, is in part constructed with redwood salvaged from a hundred-year-old aqueduct and slabs of marble pulled from public baths set to be demolished. Gesner’s current projects include two livable geodesic domes several miles from the ocean (Buckminster Fuller’s revolutionary concept, Gesner says, looked good from the outside but wasn’t very practical inside), the Autonomous Tent (low-priced, quickly erected portable living spaces you can order online), and a series of mushroom-shaped homes patterned after tree houses in the Los Angeles suburb of Eagle Rock.

Harry at his drawing table. His studio is perched in the tower of the Sandcastle.

The day after his encounter with the dolphins those ten years ago, Gesner was again in Malibu waters, trying to communicate with the mammals. This time, he was encircled by a pod of dolphins, and several of them joined Gesner on a wave, surfing in it as he surfed atop it. Again, he scurried in to shore, where the same couple sipped their afternoon cocktails. “Did you see it this time? Did you see it?” Gesner asked, out of breath. They answered by bowing to the architect as if he were some god. “Yes. We believe. We believe,” they told him. “You are not nuts.”

“I’m always changing with the world,” says Gesner, who was married to the actress Nan Martin until her death in 2010. “But I’m a lap or two ahead. I’m designing for the future, not for the present. My designs are not like cookie-cutter things where you fall into line with everybody else. I like challenges. They call me a maverick, and that means I don’t follow the normal trend of things. Which I guess is what makes me unique.

“You might say my enthusiasm for life keeps me young. I am more creative now than I was in my earlier years. Now, it’s mental, not physical.”

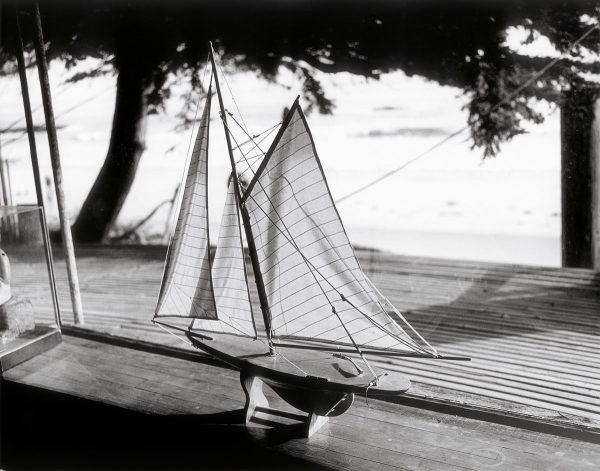

A boat always in the window of the Sandcastle.

See more in At Large Magazine vol. 3