Scene of the Crime

Written by Joseph Akel

The author of Black Dahlia and L.A. Confidential among many others, James Ellroy is one of America’s great novelists with a knack for bringing Los Angeles’s seamy underbelly to life.

Perhaps no other writer has better captured the criminal landscape of Los Angeles’s bygone era than James Ellroy. An author of prodigious output, Ellroy’s novels portray a gritty, violent city; one where the glamor of post-WW II Hollywood shares common ground with the felonious underworld of the Southland. For the uninitiated, Ellroy is best known for the film adaptations of his novels Black Dahlia and L.A. Confidential. Along with The Big Nowhere and White Jazz, the four novels comprise what is referred to as the L.A. Quartet, and, as a whole, provide readers with some of Ellroy’s most memorable characters — among them, Dudley Smith, the corrupt Dublin-born detective who mingles with silver screen starlets and gang leaders, and Edmund Exley, the ruthlessly ambitious career officer whose moral compass would seem to share a true north with Smith. Along with his Underworld U.S.A. trilogy, Ellroy’s novels span some six decades of American history, and mark the author as a unique chronicler of our day. Already at work on the Second L.A. Quartet — the first title in the series, Perfidia, was released in 2014 —Ellroy shows no signs of slowing down. Here, he discusses the various inspirations for his novels — among them the murder of his mother when he was a child — and the icons of American crime fiction. And, whatever you do, don’t call Ellroy’s writing noir.

JA What was the allure for you, in writing the L.A. Quartet with Los Angeles in the 1940s and fifties? To me, there is something about that time in which I view America through an almost mythological lens. And why have you decided to return now with the Second L.A. Quartet?

JE Well, I was born in Los Angeles in 1948. So, I’m still a year shy of 70. And, from my earliest recollection, I’ve thought about the past. Most specifically, America in the periods preceding the Second World War and the decades just after it. Here’s a brief anecdote that explains this.

It was 1956, my mother was still alive. I was 8 years old, I was brushing my teeth in the bathroom of this little pad we had in West Hollywood. I believe that, because of the prevalence of World War II in the American imagination, that I thought at the time the war was still going on. I said something that alerted my mother to this misconception. She said, au contraire, sonny, the war ended in 1945, three years before you were born.

“Where the hell else am I gonna go? L.A.! At least I know where everything is.”

JE I couldn’t believe it then, and I still can’t today. Of course, I’m kidding you, here. I was always reading about the past, looking at old magazines. I remember there was a photograph of an informal procession of cars, a makeshift parade going eastbound on Wilshire Boulevard — I could tell by the buildings that it was eastbound — on VJ day, in mid-August of 1945. There’s a line of civilians waving to the civil soldiers and sailors in uniform who are in the procession. There’s a good-looking dark-haired woman waving at the boys, and I thought about that woman just about every day since first seeing that photograph, say fifty-seven years ago. Then, of course, there’s my mother’s murder in 1958, which serves to fix my curiosity of the 1950s.

And you know, I thought that at some point in time that, as a person reached these hallowed ages, there would be a cessation of memory or it would lose its sharp edge. But, au contraire, my net just casts back that much further in time.

So, to wrap up this broad question of yours, in the winter of ’08, I had an apartment. I was two and a half years into my divorce, I had a pad in an old deco building on Rossmore on the edge of Hollywood. On a cold, rainy night, I was looking southbound on Rossmore, digging up my solitude, wondering why I didn’t have a girlfriend, and all of a sudden, a series of images came into my mind: a great many forlorn-looking Japanese in the back of a U.S. Army transport vehicle, headed up the snow-covered pass of the Manzanar Internment Camp in the winter of 1941-1942. Within brief moments, I conceived the Second L.A. Quartet. There would be four novels; they would take characters from the first L.A. Quartet and the Underworld U.S.A. Trilogy, and place them in Los Angeles as significantly younger people during World War II. The first novel would be called Perfidia, and it would be about the murder of a Japanese family on the day for Pearl Harbor. I knew that Kay Lake would be the female lead; that a real live policeman, a Major Parker, would be her love interest. I knew that Dudley Smith, the chief villain of the L.A. Quartet, would also be there. This also came to me within six or seven seconds.

JA When you began the first L.A. Quartet, were all four books mapped out as readily?

JE I wrote Black Dahlia because I had to write Black Dahlia because I had been obsessed with the case for many, many years. I delayed writing it to the extent that I did because of Gregory Dunne’s marvelous novel, may Mr. Dunne rest in peace, True Confessions, which is his Irish Catholic extrapolation of the Black Dahlia murder case. Although, thank God for me, he calls his victim the Virgin Tramp. His is a very fantastical portrayal of post-war Los Angeles, so he left the door open for me.

Cut again to a dark and stormy night, although, I was living in suburban New York, at the time. I had a revelation, and the revelation was that whatever I can conceive, I can execute. In the wake of that revelation, the breadth of the pivotal volume of the L.A. Quartet, L.A. Confidential came to me.

JA Of all your novels, is there a character that you are particularly attached to?

JE It’s Kay Lake, and it’s Kay Lake in Perfidia. I think she’s the culminating human achievement of my career to date.

JA Your style of writing is very specific and, for me, calls to mind the likes of Don DeLillo, or John Dos Passos, maybe even Nathanael West and his novel, The Day of the Locust. There is, in your use of language, a style not quite paratactic, not quite fantastical, but somewhere between. Which also captures what I would imagine to be the cadence of language at the time, but also decidedly not of it. Case in point: In Perfidia, the way in which we come to understand Dudley Smith’s machinations closely resembles the language of the time, free of the aphorisms or the idioms of contemporary culture today.

JE Your grasp is right. It’s imaginative, it’s inventive, it’s the result of my long-standing, really lifelong historical immersion. I always have to tell people going in, interviewers — I haven’t had to mention it to you, and it hasn’t come up at all, thankfully — that nothing in my books is meant to stand in for anything else. Nothing in the book that I write, except the month of the Pearl Harbor attack is meant to reference current events. Don’t ask me questions about this because I’m going to say, ’I don’t know’, ’I don’t care,’ or ’no comment.’ People seem to have no language for history as its own self. It’s its own language. And it’s an imaginative language, for me.

JA Speaking of history, in terms of your literary influences and predecessors, what did you read as kid and where does Raymond Chandler fit into all of this? Is he the godfather of American crime writing?

JE Now, Dashiell Hammett is darker, is deeper, is more important than Raymond Chandler. He preceded Raymond Chandler by the better part of a decade, even though he was a younger man. Chandler was born in 1888, and Hammett was born in 1894. I can’t reread Raymond Chandler today. The books are overwritten, plot-wise, they’re incoherent, I don’t believe Philip Marlow, this character. What I read as a kid, I can tell you exactly. I was 17 years old and working at a public library in the late summer, mid-fall of 1965. Starting to run wild, as a youth, peeping in windows and breaking into houses to sniff the under garb of some rich girl that I found alluring. I was reading Raymond Chandler, reading Dashiell Hammett, reading James M. Cain, reading Ross Macdonald.

JACalifornia, and particularly Los Angeles, plays a large role in the lives of the authors you’ve just mentioned as well as the setting for many of their novels. Is there something specific about the state that lends itself to a genre, perhaps to its origins in the U.S.?

JE The origin story would be, if anything, geography is destiny, I always say. In speeches I give, I note that Raymond Chandler settled there when he was an oil company executive in the mid-1920s. There’s that. There’s James M. Cain’s landing there, and again, he somewhat precedes Raymond Chandler. Raymond Chandler started publishing short stories about 1935 and I think Cain’s first great novella, The Postman Always Rings Twice, was published in ’34.

They were there, and they were inspired to write novels of murder. Then, you have Ross Macdonald — Kenneth Miller in real life — who was born in Los Gatos up near San Francisco, but his people were Scottish Canadians. He spent most of his youth in Canada. Then came back to live in California and then settled after college in Michigan, he settled after Navy Service in World War II, in Santa Barbara and started writing his marvelous books, and I could talk about them endlessly because I’ve got each and every one of them on a shelf over here.

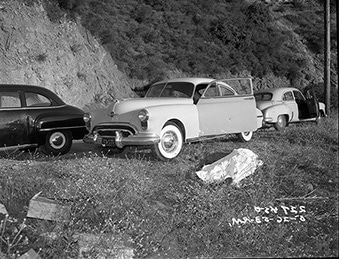

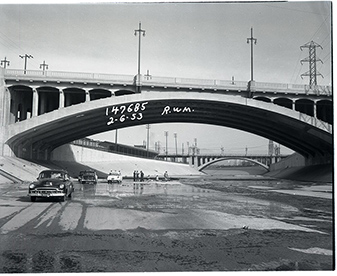

All images courtesy the Los Angeles Police Museum

JA Would you say there is a concurrence between the allure of Hollywood, the ambitious mentality for many who went — and still go out there — and the sometimes criminal, generally tragic, behavior that ensues?

JE Well, my father was a Hollywood bottom-feeder. When I was 11 years old, my father who was from Boston and had a thick Boston accent, said to apropos of virtually nothing, “Hey kid, I fucked Rita Hayworth,” and such was my relationship that I said something along the lines of “Fuck you dad, you did not.” He launched into a song and dance about being her business manager and having, in fact, arranged her wedding to Aly Khan in Paris in 1949, the year after I was born. As it happened, I read through a biography of Hayworth ten years after my mother’s death, and all of this was in fact validated.

There was always film biz chat among my parents at the earliest stages of my memory because they separated when I was seven in ’55. My mother wet-nursed an alcoholic comedienne named ZaSu Pitts. My father did Glenn Ford’s income tax. He was an accountant, he had this Rita Hayworth gig going. I, allegedly, spilled grape drink all over Rita Hayworth at a hot dog stand. Ultimately, that “L.A.” biz history is social. And history, all of it for me, it’s psychological in origin.

JA What do you love about L.A. so much?

JE I don’t

JA You don’t?

JE Up front there. I do not want to live there. I got tired when Helen, you know my wife and I, broke up, and the woman in San Francisco who I was engaged to dumped my ass. I needed to go someplace. Helen was living in Carmel, Joan had killed off the Bay Area for me, where the hell else am I gonna go? L.A.! At least I know where everything is. That’s just it: Geography is destiny. I very much like Des Moines, Iowa. And, it’s a little warm. In fact, it’s way hot, it’s on the Missouri River, but if it were any kind of a spur for me to live in Des Moines, Iowa, I would live there. My favorite town in America is Cold Spring, New York.