Eden

in the

east end

Lorenzo Vitturi’s Dalston Anatomy

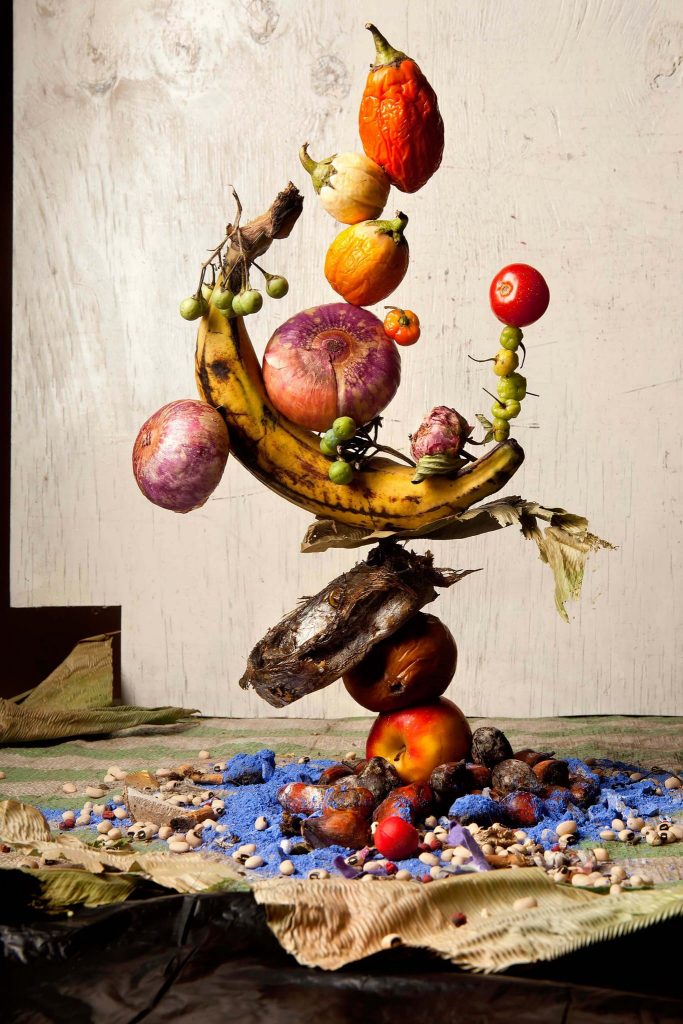

Lorenzo Vitturi From The Series Dalston Anatomy Green Stripes #1, 2013 Giclee print on Hahnemühle bamboo paper ©Lorenzo Vitturi Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

In 1551, Pieter Aertsen, a Belgian painter living in Amster- dam, completed work on his painting Butcher’s Stall with the Flight into Egypt. To be sure, Aertsen’s lifelike depiction of a butcher’s stand, gruesomely stocked with a freshly slaughtered cow’s head, smoked pigs’ feet, and fully feathered guinea fowl, undoubtedly impressed viewers then, as now. And yet, what would have truly stood out to any observer of the age was not so much Aertsen’s skill as what he chose to depict in the background of the stall: Joseph and Mary’s escape with the baby Jesus from the murderous King Herod (Matthew 2:13–23, for those who need brushing up). Indeed Aertsen, known in art historical circles as a Mannerist, had, in what was nothing short of a radical gesture, located the sublime—the biblical—in the everyday setting of an open-air butcher’s market stand. Far from the empyreal realms that had come to define Renaissance depictions of the divine, Aertsen found traces of Providence in the everyday marketplaces around him.

Similarly, for contemporary Italian artist Lorenzo Vitturi, London’s well-known open-air Ridley Road Market serves as the inspiration for a series of vibrantly colorful, intricately constructed photographic still lifes. Drawing inspiration from the Hackney neighborhood in which the market is located, the large-scale works comprising Vitturi’s series Dalston Anatomy are equal parts documentation of and ode to the various cultural communities that have settled in the north London neighborhood over the past hundred years, among them a steady stream of immigrants from Africa, the Middle East, and the Caribbean.

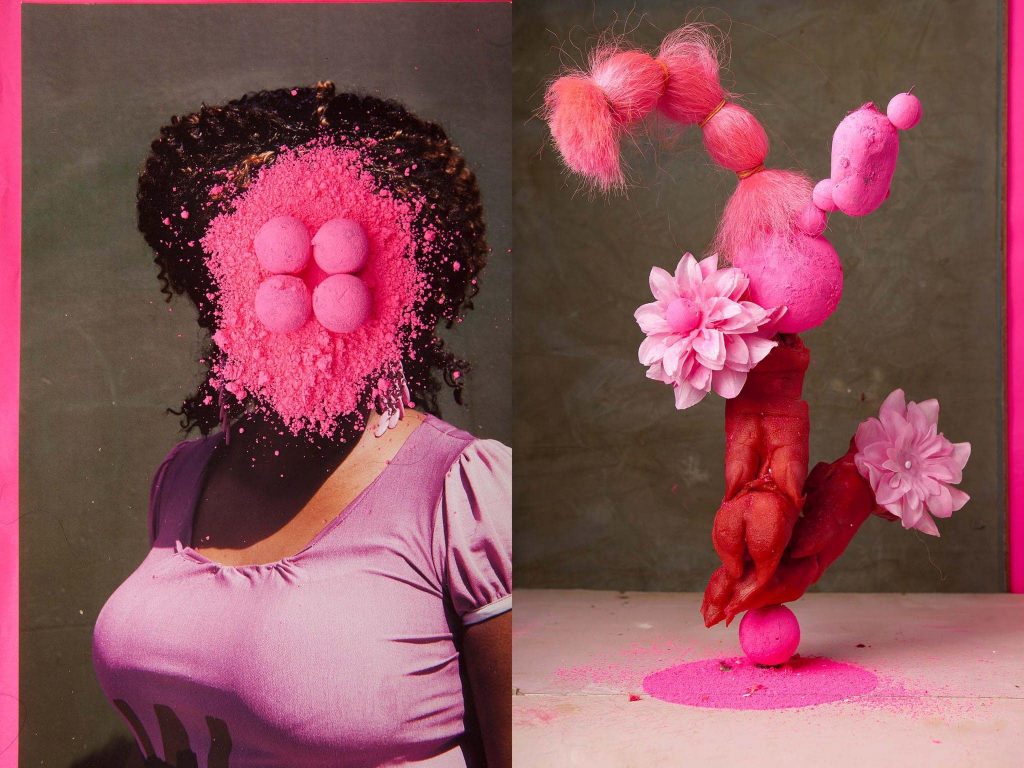

Lorenzo Vitturi

From the series Dalston Anatomy Pink #1&2, 2013

Giclee print on Hahnemühle bamboo paper

©Lorenzo Vitturi

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

First scouring the streets in and around the market for remnants (pigs’ feet, balloons, scraps of fruit), Vitturi returns to his Dalston studio with his findings, often leaving his horde to rot for several days. The discarded objects are then fashioned by Vitturi into stacked, architecturally precarious sculptures that call to mind the food-based sculptures Irving Penn created for Harper’s Bazaar. However, whereas Penn’s images favored a clean, highly minimalist approach, Vitturi embraces a hap- hazard aesthetic, albeit one that belies the complex nature of their construction. As with Green Stripes #1 (all works 2013), a scattering of black-eyed peas and blue pigment powder adorn the base of an impossible tower of dried apples, rotting onions, and small fruits, all perched ever so delicately on the inner curve of a decaying banana. Similarly, in Red #1, a grouping of orbed fruits, one already partially sliced and perched atop two dried pep- pers, are dotted with various flower buds, all resting, somehow, on a brick, itself draped and wrapped with what is either twine or quite possibly leftover noodles.

In several diptychs included in the series, such as Yellow Chalk #1&2 and Pink #1&2, Vitturi has taken to placing photographs of his sculptures alongside manually altered portraits of market attendees. As with the latter diptych, a gravity-defying spire including pigs’ feet, silk flowers, and a synthetic wig—all in shocking hues of cotton-candy pink—is shown to the right of a young woman, whose face is obscured by a thick dusting of equally vibrant pink pigment powder and four small fruits. In the case of the portraits, Vitturi first photographs his subject, then reworks the surface of the image, adding various pigments and other found objects, before photographing the altered image, printing it out on bamboo paper, and exhibiting it alongside the photographed sculpture that shares a corresponding color value.

Formerly a set painter for the Rome-based film produc- tion studio Cinecittà, Vitturi’s elaborate sculptures—which extend to the fabrication of the rooms they are photographed in—reflect his interest in constructing visually arresting, if not altogether improbable, images for the viewer. And, principally, what is fleeting for Vitturi is the very neighborhood from which he draws inspiration. Facing increasing gentrification, the mul- ticultural communities that give Dalston its flair are once again facing the same kind of marginalization that first led them to the neighborhood well over a century ago. Economics, it seems, are very much at the heart of Vitturi’s creations. In that sense one can all too easily draw a line from Aertsen to Vitturi, identifying in both a desire to depict in the sundries of everyday life the glories of human capability.

Lorenzo Vitturi From the series Dalston Anatomy Yellow #2, 2013 Giclee print on Hahnemühle bamboo paper ©Lorenzo Vitturi Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

See more in At Large Magazine vol. 2