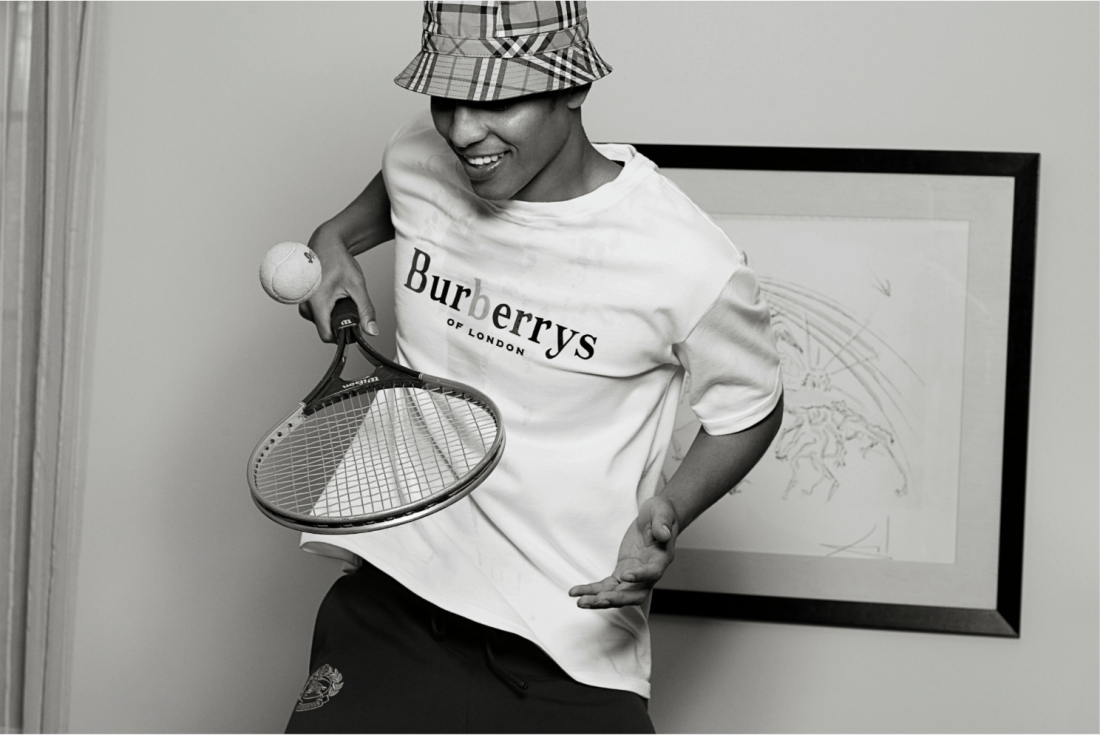

GERON MCKINLEY

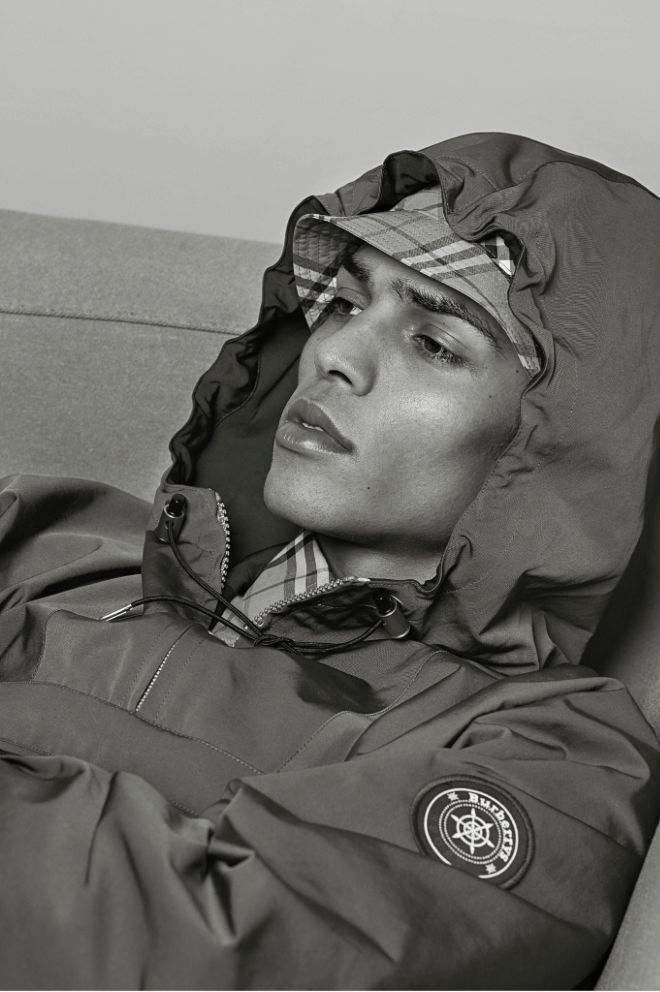

All Clothing Burberry Spring/Summer 2018

Written by Joobin Bekhrad

Photography by Randall Mesdon

Styled by Paul Sinclaire

You may not know Geron Mckinley, but, unless you’ve been living the anchorite life, you’ve seen him. Despite being only twenty-three years old, Geron’s (pronounced Je-rahn) face is just about everywhere in America and Europe. From Gap ads to Vogue photo shoots, the model has come a long way from his humble beginnings in his hometown of Compton, California in a remarkably short period of time. That isn’t to say, however, that he’s forgotten his roots, or that there’s somewhere else he’d rather be right now. Whether in Paris shows or in New York studios, Compton—and its people—are always on his mind. One might think that, given his situation and age, Geron would want to break free of the burbs and see the world; but he has other plans.

While Geron doesn’t complain (much) about the modeling gig, he’s always been after something more than fame and fortune — hence his decision to establish Concreet, a charity fashion label providing funding to help Compton residents realize their full potential. “I felt like when I first started [modeling],” he says, “I wasn’t necessarily fulfilled. I was nineteen, and I was in every store in America when it came to Levi’s. For me, as a kid, it was like, well, that’s cool, but I still have to see the kids and I still want to help the youth out. [There] was kind of like a void that I tried to fill with them myself by starting [Concreet].” The decision to engage in philanthropy wasn’t something that came about when he began modeling, though; he’d long wanted to give back to his community and make a difference in his hometown. “I’ve just always wanted to help people, whether as a business or not.”

Because there’s so much life beyond modeling—trust me.

Naturally, Geron’s upbringing and family inform much of the philosophy behind his charity work. “I grew up with my mother’s heart,” he says in reference to whom he calls his number one hero. It isn’t only her kindness that inspires him, but also her work ethic. “My mother worked two jobs while I was growing up. My entire life, my mom has been working.” It’s clear when talking to Geron that he grew up in a loving and supportive household. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that he had it easy as a kid in Compton, or had anyone to help him find his voice when he most needed it. “When I was a kid, I struggled. Growing up, there weren’t really any promises that were like, oh yeah! This is for sure! [There wasn’t anyone] who was really willing and ready to give me an open hand. So for me, growing up, I was just kind of ready to help somebody else and let somebody else know, OK — there’s somebody else here to help you. I think that really dictated how I am now … No one wants to see anyone do better. I’m kind of the opposite.”

Geron’s lack of opportunities growing up in Compton translated into his choice of name for the brand itself. In this respect, it goes beyond simple urban imagery to become a poignant metaphor. “Concreet was based on a solid opportunity … We wanted kids to know that this was something for real, something solid … We’re a solid promise to helping people … That was the whole thing behind the name, you know.”

Up until this point, Geron has only been mentioning the kids of Compton, which prompts me to think about his foundation’s mandate. Does Concreet only help kids up to a certain age? Who, exactly, is eligible for the financial sponsorships they’re committed to providing? “As far as helping people,” he says, “we can’t just hold on to one demographic and be like, this is who we want to help. If I can help a twelve-year-old the same way I can help a thirty-five-year-old, trust me — I’m going to do so.” Fair enough; but what qualifies one for a scholarship? I ask him about Concreet’s criteria and the factors that determine who gets what and why. “[Criteria] is something we struggle with every day, because some people need more help than others. Who am I to say who I can help and who I can’t? I look for [commitment], because if [people] can show that they’re really committed, then it just means they’re hungry, and that’s the first step in accomplishing anything. So, essentially, that’s the criteria for me: want something.”

Alright, I say to myself. Let’s suppose I’m a hungry young thing in need of a hand up from a fix. How do I apply for a Concreet scholarship? “Since the beginning, it’s been us finding kids,” Geron explains. “We’ve been going to schools, we’ve been talking to a lot of campuses … And we do use a lot of social media. Social media is where people [mostly find me] … I’d say, give us another three to six months, and we should actually be taking some scholarship applications.”

As we haven’t yet discussed any actual scholarships, I assume that these have yet to be awarded. It turns out I’m wrong, and that Concreet is more active than I’d thought. “We’ve given many scholarships,” he says, before filling me in on a schoolyard reality. “Did you know that if you don’t pay athletic dues, you can’t play on a sports team?” Never having been fond of sports, I reply that I didn’t. “I don’t see that as something kids should worry about at the age of nine. We went ahead and paid athletic dues and made sure the kids played.” As for specific examples, he points to a woman by the name of Antoinette Brock, who runs the Don’t Throw Away the Crust blog. “She travels the world to these really desolate places, and her main goal is to not let the world forget about them. We’ve given out scholarships like there’s no tomorrow.”

I’m singing his praises now, but am also wondering why Geron felt the need to establish a charity of his own, instead of donating money to his favorite nonprofits. “I know this is supposed to be about you asking the questions, but let me ask you a question: what do you know about the percentages that most nonprofits actually donate?” I tell him I’ve always been skeptical. “As you should be,” he responds. “There are these nonprofits that only give away ten percent of what’s actually being donated to them. It’s like, well, where’s the rest of it? Who am I helping? … I couldn’t trust [others], so I decided to do my own thing.”

Just as Geron is skeptical of certain charities, he also has his principles when it comes to working with fashion labels. I ask him if he’s ever, for instance, rejected working with particular brands because of unethical practices. “There have been a couple like that,” he admits. “I don’t necessarily agree with the way they do things, certain things that don’t fit with my morale and my character.” Asked whether he feels he can afford to reject particular offers now, he tells me he’s always stood his ground. “I’ve been like that from the start, but I think now I have more of a voice, and my agents and these brands are actually listening. It’s easy to be a face in this industry, but to sit here and be a face and say something — ah man, that’s not something they’re used to. It’s taboo, almost.” Geron puts it mildly. Speaking about a recent collaboration between Concreet and Forever 21, he tells me that he very much called the shots. “[I asked them], what are you going to do for the youth if I work for you? I understand I can sell your clothes, and I know you want me to sell them, but how about the kids I’m around all the time? A lot of brands want to shoot, but I’m not really for shooting every brand. Forever 21 just happened to be willing to give a little in order to get a little.”

Expanding on the issue, I mention philanthropic initiativeson behalf of fashion labels, such as the Burberry Foundation, which he sees as vital and part of a growing movement. “Why do we know about the clothes more than the philanthropy? There should be a type of balance. I think that’s going to be the new business model in the next few years. We have to start moving like that, because, if not, it’s just going to get out of control: the rich are going to get richer, and the poor are going to get poorer.”

For the time being, Concreet is focused on designing clothes, which it does in partnership with local talent, who sometimes offer their services on a voluntary basis. “We just try to find up and coming people who are ready and willing to work, and really express or show what they can show, and we go from there,” he says. “We give them opportunities to do what it is they want to do.” However, Geron isn’t planning on limiting Concreet to clothes; it’s a much bigger picture he’s looking at. “We don’t just make clothing,” he tells me, “we make products … I’m thinking of working with brands like Apple, Samsung, and Beats by Dr. Dre — that’s the type of frequency I’m on. Me and [my business partner] Mario were even discussing coming up with watches.”

Geron makes no bones about his commitment to and passion for his new philanthropic endeavor. I’d felt from the beginning of our conversation that it was of even more importance to him than his modeling career, and, it turns out I’m right. While he doesn’t have any plans to quit modeling entirely, Concreet has certainly changed the way he approaches it. “I would still like to [model] to the fullest extent if it’s helping Concreet. I think that’s how it’s going to balance itself out, because I’ll still be working these jobs, but they’ll be jobs I’ll be working because they’re helping Concreet …I don’t want to get out of modeling, but juggle it. I want to be a circus act when it comes to all these things.”

If Geron hasn’t changed in terms of his values and ideals, he undeniably has when it comes to setting goals. “Aside from modeling, I didn’t really have much going for myself,” he says of his pre-Concreet days — and that was afterhe had unintentionally entered the fashion business. Today, he knows exactly what he wants, and how he’s going to get it. He’s also determined to place further attention on Concreet, “Because there’s much more life beyond modeling — trust me,” and he paints a rather clear picture of what the next few years hold in store for the nascent brand. “Concreet will be self-sufficient by then. You’ll definitely be able to apply for a scholarship, and I think we’ll have our first facility where we’ll be able to really give people the Concreet experience, where we’ll pledge to really give opportunities in art, sports, music, and entrepreneurship.” He’s also excited about Concreet’s forthcoming website, which he says will allow donors to track exactly where their funds are going, and how they’re being used. And, as much as he’ll always be a Compton boy at heart, fighting it out in just the burbs isn’t something on Geron’s agenda. “We’re here to help the world,” he emphasises. “We’re trying to go global, man!”

Joobin Bekhrad is an award-winning writer who has authored numerous books of prose and poetry. His writings have also appeared in publications such as The New York Times, The Economist, The Financial Times, The Guardian, and the BBC, while he has been interviewed by ones like Newsweek, Monocle, and PRI.