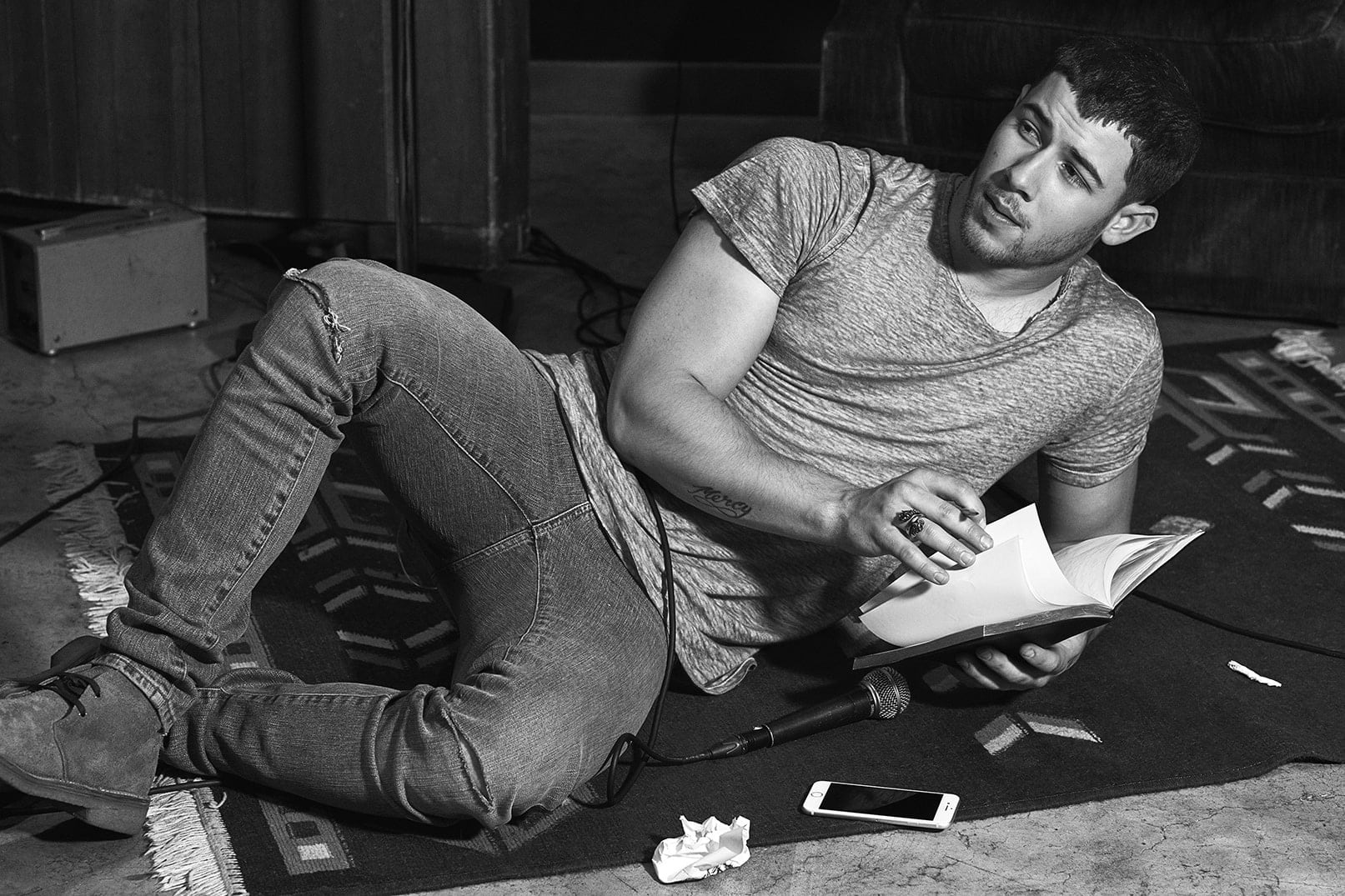

Nick Jonas

Word for Word

Photography by Randall Mesdon

Written by Maxwell Williams

Styling by Avo Yermagyan

T-shirt John Varvatos, Jeans Saint Laurent, Shoes, Ring Gucci, Journal Armani/Silos

Nick Jonas’s abs.

I could probably finish the profile there, and most of you would be satisfied. “Abs” could be synecdoche for “Nick Jonas,” as in, “For the forty-five minutes or so, I chatted with abs on the phone about his life.” For whole demographics — men and women — the words “Nick Jonas” evokes six fat-free tummy stones, hard to the touch, a happy trail of fur tracing a line to the belt.

“He’s so sexy I can’t take it,” my friend James texts me when I tell him I’m interviewing Jonas (n.b. I sent him a picture of a shirtless Jonas to inspire these words).

To people like James, Nick Jonas is a sex bomb; a long ways away from his son-of-a-preacher-man beginnings. In the late-aughts, young girls fawned over young Nick and his brothers Joe and Kevin. Now, it’s men (and women) for whom the sexiness arouses.

Before the abs, the Jonas Brothers were almost unbelievably popular, and much of that had to do with their squeaky-clean, brotherly love image. The New Jerseyan trio sang at George W. Bush’s Easter Egg Roll in 2007. They wore purity rings. They played two songs on Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve. They made a deal with Disney’s Hollywood Records, and appeared on Hannah Montana. They were a mom-approved, sexless, Jesus-lovin’ boyband living in a pre-Bieber world.

But something had always been bubbling under the façade.

Nick was discovered first, at 6, when he was singing in a hair salon while his mom got a ’do. Another patron heard his sweet voice and gave mom the info of a talent agent, who almost immediately sent him on Broadway auditions.

Religion was part of the initial package: His first Broadway role was as Tiny Tim in A Christmas Carol in 2000. Nick released a song written with his dad, Kevin Jonas, Sr., then a Pentacostal minister, called Joy to the World (A Christmas Prayer), and then a follow up single, Dear God, both put out before the Jonas Brothers were conceived of as a band. Good Christian stuff, all.

Then, a change began to happen, and it was actually at his father’s encouragement. It started when parishioners from Kevin, Sr.’s church came to see the local pastor’s son make good on Broadway, and one of those plays happened to be Les Misérables. Nick was dazzling theatre critics as Gavroche, the young street urchin-turned-revolutionary who confronts the police inspector Javert.

“And my character sings, ’What the hell?’ and flips somebody off in the show,” recalls Nick, who had been concerned the churchgoers would turn on him. “I remember I had an important conversation with my father where we talked about the importance of telling stories, and how there’s a difference between the person that you are and the person that you can play. He opened my mind in that way, and helped me understand at an early age that as an actor, even as a kid, it was my job to impact someone’s life, and bring a story to them that would hopefully bring them some perspective or compassion or understanding of someone else’s journey.”

The paternal lesson of empathy deeply affected young Nick, and the proximity to a community of people he worked with and loved solidified it. Any story, this one included, profiling Nick Jonas, would be remiss to overlook his current involvement in LGBTQ advocacy.

Jacket, T-shirt, Saint Laurent, Bracelet Title Of Work

“I think there was this element of being deeply rooted in the LGBTQ, because — theatre — my closest friends that I made at an early age who were LGBTQ,” he says. “So, I made some great relationships early on, and never understood how someone would not accept someone for them being who they were.”

Nick’s allyship has manifested itself when he and Demi Lovato cancelled two shows in Raleigh and Charlotte in 2016 to protest North Carolina’s House Bill 2 (HB2), better known as the “bathroom bill,” which requires people to use the restroom consistent with the gender on their birth certificates, regardless of their identity. He has performed at Pride events in Pittsburgh and Sydney, Australia.

“Two of my favorite gigs I’ve ever played, and I hope I can play more Pride events,” he says. “Or just attend, hang out, and have fun.”

But it’s not just solidarity that has guys like my friend James proclaiming him a “gay icon.”

Nick unbuttoned a button-down in a New York gay club in 2014 for the debut of his hit song Jealous, and he performed his song Chains while in bondage chains at the G-A-Y club in London. He’s appeared on the cover of Out and been profiled in The Advocate, and he even spoke at a vigil in New York for the victims of the Pulse Night Club shooting. He plays a faking-it gay frat guy on the first season of the Fox slasher-comedy Scream Queens; and he’s a closeted MMA fighter on Kingdom, an Audience Network show, which is ending in August after three underrated seasons.

“I wish I could say it was some big plan that I was in Kingdom and then also in Scream Queens playing these characters, but these are roles that I really loved, and had to fight hard to get them, as well,” he says. “So, it was not a big plan, it just happened, and I’m thankful it did, because I got to tell some really unique stories.”

So, Nick isn’t gay, but he plays one on TV. It has led to impassioned criticisms in The Fader and Huffington Post, which have accused him of “pandering to” or “queerbaiting” an LGBTQ audience (particularly, his speech at the Pulse vigil was considered “taking up space”). And some of these positions are well-argued.

T-shirt John Varvatos, Jeans Saint Laurent, Journal Armani/Silos

“Even in my desire to disappear and take a step away from the journey that I was on, there was still real ambition and drive towards something else.”

Though Nick Jonas isn’t the first straight pop star to court an LGBTQ following (see: Cher, Kylie Minogue, Janet Jackson, Madonna, Lady Gaga), he is among the first heterosexual-identifying male pop stars to actively promote to gay audiences. This isn’t a problem, per se, but it does open him up to these kinds of analyses. But it also begs the question: which came first?

Boy bands have historically been the subject of gay male attention and speculation, from the New Kids on the Block and the Backstreet Boys to One Direction and the Jonas Brothers. Nick has made some mistakes, yeah, and he’s seducing gay fans, sure, but it could be argued that those fans were already there for him.

Nick grew up with these fans, and it left an indelible mark on him.

“As I got older, and I started to think about causes that I was passionate about, acceptance became the biggest one, and being an ally to a community that’s been incredibly supportive of me,” he tells me.

A day before the interview, I find myself clicking through a slideshow on some trashy website called Tragic: 32 Child Stars Who Died Shockingly Young. River Phoenix, Brad Renfro, Jonathan Brandis. Corey Haim. It’s an all-too-familiar tale of drugs, maybe suicide, or some combination of the two. Another slide show has child stars — Drew Barrymore, Mary-Kate Olsen, Edward Furlong and Jodie Sweetin, among them — who have battled addiction. Some child stars like Haley Joel Osment and Macaulay Culkin, for instance, simply disappear altogether.

When you’re famous from the age of 6, like Nick Jonas, it can be a struggle to not let yourself become emotionally stunted while you find footing as a grown-up.

“I have empathy for anyone who’s lived in complicated scenarios in their upbringing,” says Nick. “It’s related specifically to child stardom for me, but also I know that there are child athletes, and children that are gifted mathematicians, and once they become an adult, [they realize] it’s a big world with a lot of really brilliant people, and it can be really tough,” Nick says.

He credits his deep-rooted family values as one reason he never turned to drugs or alcohol as a means of escape, but he says that it doesn’t mean the years between the Jonas Brothers and his solo career weren’t trying.

“I’m really fortunate to be in a spot where I got to restart my career at 21,” he says. “But I get it, and I understand the emotional toll it can take to have success so early on. Numbing becomes something that is the only way to deal with some of that pain, or so that person might see it. So, on my end, there’s absolutely no judgment ever, because I really understand it.”

He tells me he recently had a conversation with Cole Sprouse, who was known by millions of adoring tweens as Cody from The Suite Life of Zack & Cody (his twin brother Dylan played Zack), a Disney Channel hit that ran parallel to the Jonas Brothers’ success. Both Sprouse brothers disappeared à la Macaulay Culkin to attend New York University, with Cole only returning this year to star as Jughead in Riverdale.

“He asked me, ’Would you have done what I did, and just gone to college?’” Nick relays. I said I would have done it if I had the chance to walk onto the baseball team. So even in my desire to disappear and take a step away from the journey that I was on, there was still real ambition and drive towards something else. I have this thing in the back of my mind that’s always pushing me to grow and get better, and I don’t think that stepping out of the limelight was really an option. But I’m glad I didn’t, because I had a couple years at the tail end of the Brothers and the start of my journey alone that were really challenging, but gave me a lot of drive to say, ’Fuck it. I want to do this.’ So, I got aggressive.”

That aggressiveness has led to a full career at just 24. His single Jealous from his eponymous solo album was a Top 10 hit. His full-length Last Year Was Complicated, mostly written during his breakup with former Miss Universe Olivia Culpo, debuted at number two on the Billboard 200.

And as we talk, he’s promoting his new single with up-and-coming British pop singer Anne-Marie and I Took A Pill in Ibiza singer Mike Posner. It’s one of his best yet, filling a space between Justin Timberlake and Jeremih, with boy-girl vocals and a plucky, minimal beat.

The *track is the first off a new album that he’s currently working on with people like young Swedish producing duo Jack & Coke, Simon Wilcox (whom he wrote Jealous with), and Justin Tranter, who has co-written songs with Justin Bieber, Gwen Stefani, Selena Gomez, and Nick’s brother Joe Jonas’s band DNCE. It’s an assemblage of people that he hopes will create a varied album of different genres; more like a Spotify playlist than an album.

“I no longer think you have to, as an artist, tie up the body of work with a ribbon, and say, ’Everything kind of sounds like this, and it’s just one thing,’” he says. “There really is freedom to be able to dabble in different things.”

Plus, he says, it’s a much more upbeat album than Last Year Was Complicated, which documented lovelorn suffering.

“The music does have this element of hope and optimism to it,” he says. “Less heartbreak. There’s maybe one song out of fifteen that I’ve written that’s about a past relationship, but even that is enlightened. I think I’m in a really free place as a person, and it’s definitely affecting my creative life. I’m loving singing with a smile on my face or with a bit of hope in there.”

Like any double threat, Bo Jackson or Deion Sanders proved themselves over and over again to their critics in both sports. Nick has to do the same in acting. Many people don’t know that he started in theatre, and when they see him on a show like Kingdom, they wonder if he’s up to the task. What they don’t expect is his versatility.

On Scream Queens, as Boone Clemens, he’s aloof and elusive and funny. On Kingdom, Nick had to put on fifteen pounds each season and train in jiujitsu to make the MMA scenes look legit. Not only that, he has scenes that require a lot of nuanced emotional depth as a gay fighter in a world of hypermasculinity.

“You’ve got to be willing to go to some deep, dark places, and this last season of Kingdom was very, very intense, and using music as an escape from that is key,” Nick says. “I feel for other actors who don’t have an alternative outlet to be able to share their life stories, or escape from some of the heaviness of acting. But then there’s things like Jumanji, which are just fun.”

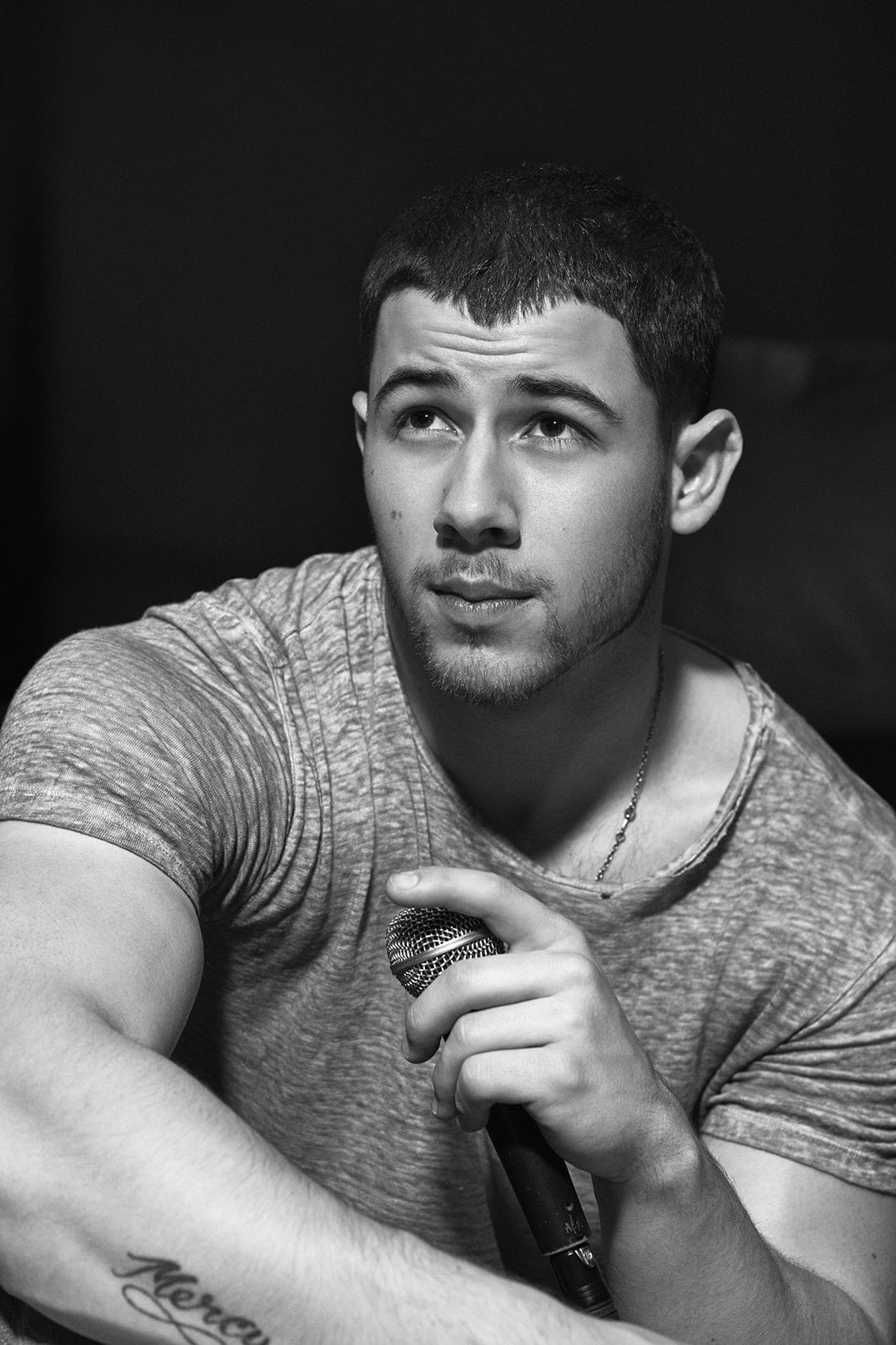

T-shirt John Varvatos, Necklace Title of Work

Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle, due out at Christmastime 2017, is his first major studio movie release, and it couldn’t be a better entrance into the film world. Nick calls the original, with Robin Williams and Kirsten Dunst, one of his favorites, which made landing the role all the more special.

“I first watched Jumanji with my dad,” he says. “I remember picking it up from Blockbuster, when that was still a thing. I watched it three times in a week. It freaked me out a little bit. It was kind of scary, you know? The day that I got the role in the movie, I was on my tour bus last summer, and it was kind of serendipitous. I walked on the bus after I had just gotten the call, and it was on the TV.”

Nick made the most of his time on set. If you do a search for the film, a video of Nick firing a toy Nerf gun at Jack Black pops up — he calls Black a good friend.

“It was a prank-heavy set. The Nerf guns became a thing to the point where we had to put them away, because we were using them too much. The other thing was, you never knew when you were going to be in one of Kevin [Hart’s] Snapchats or Instagram stories or whatever. So, you had to be aware of every second, because he would pull his phone out, and he might be secretly filming you. He did this whole bit where he would play my songs [on his phone] and just sit down next to me like everything was normal, and filmed it all.”

Though he can’t say much about his character — the secrecy is something of a plot point — he does comment on the minor uproar about the film’s plot: in the new film Jumanji is a vintage video game instead of a board game.

“I love that it’s evoking that much passion,” Nick says, laughing. “It means that the first one is truly loved, so I’m hopeful that people that love it that much give it a shot. It’s a very small detail within the grand scheme of things. And this movie is its own adventure. Our references to the original within our movie really do honor it.”

The fact that Nick is recording a record and acting in a blockbuster film is all the more remarkable when you realize he does it while managing Type 1 diabetes — a disorder where the immune system mistakenly attacks the cells in the pancreas that make insulin, a hormone that allows your body to use sugar.

When Nick was 13, as the Jonas Brothers were gaining traction on a school tour, he began to lose weight, and he was thirsty all the time. Severe leg cramps robbed him of a good night’s sleep. So, he went to the doctor, and his blood glucose level had spiked to over 800 mg/dl — normal blood sugar levels are 70 to 120 mg/dl. He had to be hospitalized for several days.

Since that day, Nick has had to handle it. He checks his blood sugar levels ten to twelve times a day. He’s on an insulin pump, where he takes insulin hourly and before he eats carbs, which turn into sugar in the bloodstream. Physical exertion and being in the sun also need to be watched. And some days, he says, “just go awry.”

Coat Greg Lauren, T-shirt Gucci, Jeans Louis Vuitton, Bracelet Gucci, Shoes Visvim

“What am I doing in this moment to be the best I can be at what I’m doing? And how am I going to be remembered thirty years after I die?”

But Nick is hopeful about the future. He is a longtime advocate for the disorder, but lately has become a champion for a cure.

“The message that I have is that this disease totally sucks,” he says. “For a long time, it was strictly optimism. My message would have sounded something like, ’I accomplished my goals while living with this disease, and you can, too.’ That is absolutely still true, but after living with this now for twelve years, I’m more aware of the fact that I really want to be a part of finding the cure.”

Cures don’t seem to be too far off. A recent article in the Wall Street Journal details progress in studies on a new therapy where doctors place lab-grown insulin-producing cells into patients, and other doctors are studying the process of retraining patients’ cells to fight the disorder.

“I want to encourage people to live their best life with the disease, but I also want to encourage other people who don’t live with the disease to do what they can to help, because I think we’re really close to making a lot of people’s lives better, and simplifying life as a whole for people living with diabetes,” Nick says.

There’s a complicated guy behind Nick Jonas’ abs. Between his hit-making music career, his burgeoning acting forays, his LGBTQ allyship, and his diabetes advocacy, he’s got a lot going on that add up to a talented entertainer.

With his fourth album and Jumanji on the horizon, Nick is entering a mature phase that will no doubt find him the object of many people’s affection. He’s always looking to the future.

Coat Greg Lauren, T-shirt Gucci

“I always think about two things: ’What am I doing in this moment to be the best I can be at what I’m doing?’ and, ’How am I going to be remembered in thirty years after I die?’” he says.

“I want to be the kind of performer and storyteller and creator that challenges people’s thinking, but also that became a part of the fabric of people’s lives. When I look at [entertainers] I love, I think about that song that played when I discovered music could affect you like that, or the play I watched that had me reeling for two weeks because I was thinking about that one scene. There’s some incredible performers and actors who have influenced my life that way, and I hope to be one of those for somebody one day.”

Somehow, I think, he already is.