FOUR E77st.

The Room

Written by STEVEN MARK KLEIN

On the second floor of a nineteenth-century townhouse, hidden among the pre and postwar wealth of the United States, yards from 5th avenue, there is a north facing room at 4 East 77th street, New York City. On February 10, 1957 it opened as the Leo Castelli Gallery. But, this article is not about Leo Castelli. Nor is it about the artists he invested in. This article is about that second-floor front room and the potential it held as well as the world created within its white walls.

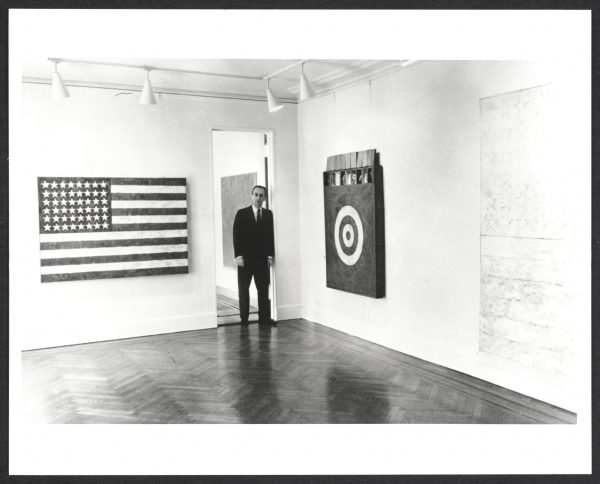

LEO CASTELLI WALKING THROUGH THE JASPER JOHNS EXHIBIT 1958

Unidentified photographer

Leo Castelli Gallery records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Truth is malleable—and our minds are so conditioned against doubt—that I can write that I stood next to Andy Warhol at his first Castelli exhibition, the Flower paintings. I turned 14 during the exhibition, which ran from November 21st to December 28th, 1964. I understand that Hedi Slimane has a photo of that meeting, and that it’s permanently affixed to the wall of his design studio. Memory files are deteriorated, so I will say that sometime in 1973, I worked as a book salesman for George Wittenborn on Madison Avenue, two blocks from the Castelli Gallery. I specialized in books on emerging artists. I sold my copy of Ed Ruscha’s Dutch Details for a few hundred dollars to take a Greyhound bus from New York to San Francisco sometime around 1976. But I’m getting ahead of myself. The room at Castelli is what this file search is about. Okay, I got that out of me.

My task is to describe the manner in which this 425 square-foot room was able to act as both an exhibition space and predecessor of many of the most original intellectual ideas to come out of the art world in the last fifty years. This is an attempt to convey the unique power that room possessed, a power that was at once privileged and democratic, a locale in which the definition of art was radically reconfigured for better—or worse.

THE ROOM STILL HOLDS ALL of its ORIGINAL MYSTERY

I recently returned to The Room one Indian summer day in September. The street entrance hasn’t changed in the six decades I’ve been walking through those townhouse doors. There’s a brass plaque on the front, as there has always been, but now it announces the Michael Werner Gallery. The vestibule is the same. You still pass through a second set of doors. In the lobby, all of the architectural details from my earliest visits are just as I’d first encountered them. On that day, the exhibition happened to be of the late Jörg Immendorff’s Café Deustchland series of oil paintings (they were originally shown at Ileana Sonnabend’s legendary Soho gallery, if I recall correctly). Sitting on the windowsill, looking at Immendorff’s Tarantinoesque slaughter, the warmth of sunlight on my back, it felt almost as if I was back at Warhol’s Flowers debut—the occasion when a photo was taken, a photo that now hangs somewhere in L.A. It would be romantic if I could relate how Leo Castelli and Leo Fitzpatrick are part of a perfect continuous loop of elevated goals and events. This is not going to happen. It’s hard to explain the room’s abstract depth, its ability to interact with numerous products of genius for over 57 years while maintaining the generosity of independent thinking and a democratic spirit of all-inclusiveness.

On any given day, the room might host a teenager from Brooklyn and the Italian industrialist Gianni Agnelli. Without each other’s knowledge, both look upon these wildly original and expository creations and form a deep personal relationship with them. To be honest, since those days I’ve rarely felt the same sense of clarity and connection I experienced in The Room. I did experience that level of communication in the fifth-floor front room of the Gagosian gallery at 980 Madison Avenue, where I was privileged to view Cy Twombly’s The Last Paintings. For a few moments, I was able to connect Leo Castelli with six decades of artists, investors and distractions to why the works were created, and why we seek those creations out. It is to experience truth.

Many mornings I’ve woken with a need to visit this room. While the works on view were important, they were not as important as the experience of entering the building and arriving in The Room; unlike the art on display (which has faded into distant memory), it still holds all of its original mystery. I have spent decades visiting the many galleries positioned to explore the art of my era, in New York, Los Angeles, Miami, London, Paris, Milan, Rome, Berlin, Zurich, Basel, St. Moritz, Tokyo, and Beijing. I have visited over a thousand galleries and museums in search of that transformative quality—a quality possessed by the north facing, 425 square-foot room.

It is to EXPERIENCE TRUTH.

The Room might be one of the reasons why I’ve spent my life in pursuit of experiences that will reframe my identity. It was an amazing matter of fate that, year after year, I happened to enter The Room precisely when the ideas that came to define our culture’s aesthetic vocabulary were being presented for the very first time. It is a matter of will that I’ve spent decades on one long journey, seeking out spaces and experiences that might endlessly deepen and reframe who I am, and my relationship to our shared world.

The Room still exists with the directive of its own truthfulness. It exists for the very purpose of dismantling any and all individuals and organizations (both personal and financial) that claim to be heir to Leo Castelli’s title of the source, the genesis, the grail of intellectual truth and power. For some unfathomable reason, truth and power reside in the room.

Is it scientific or strategic power The Room possesses? All I can say is that it can be very dark outside of that room. And I want to believe that as long as I am still here, that room will be, too.