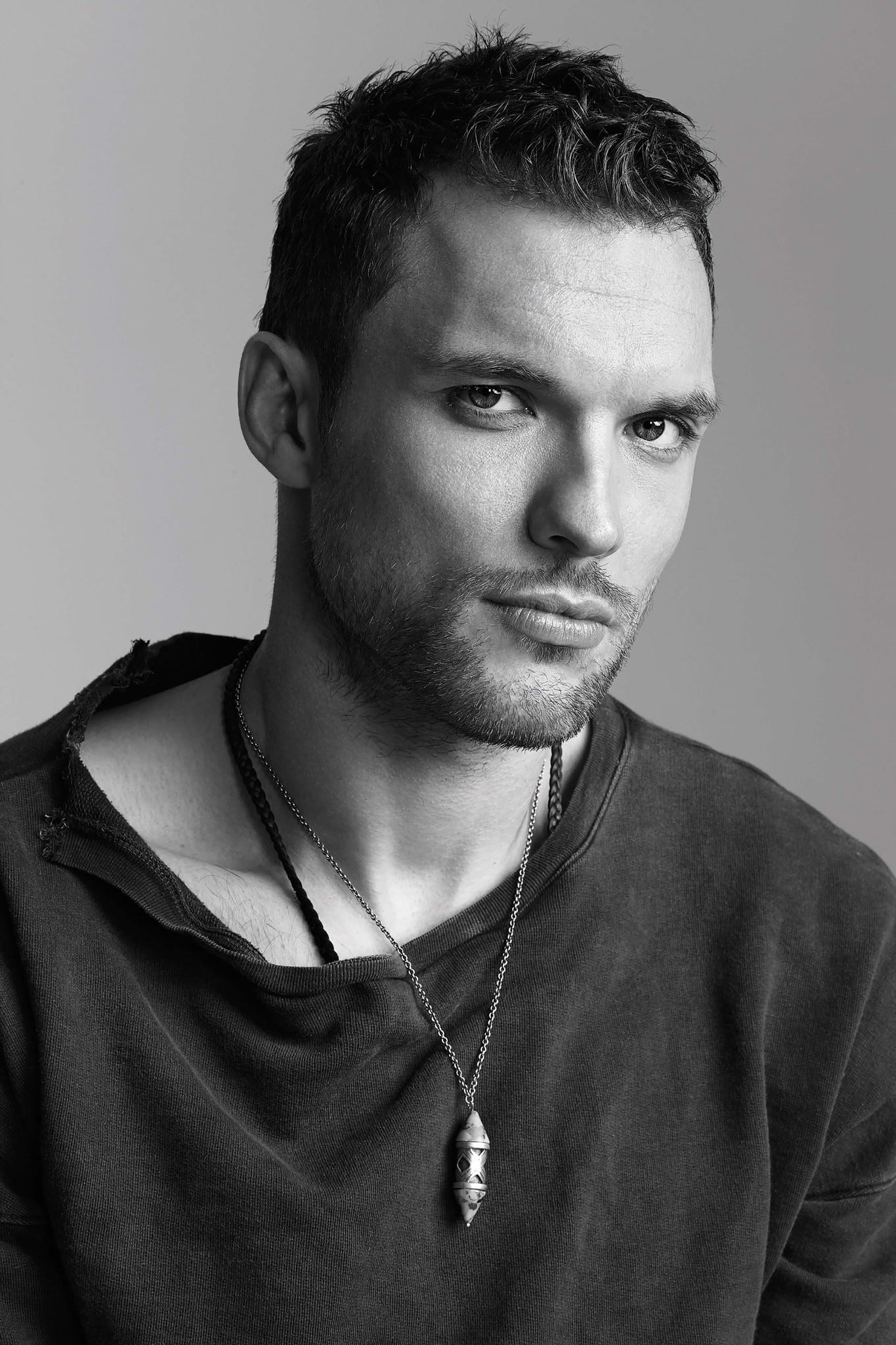

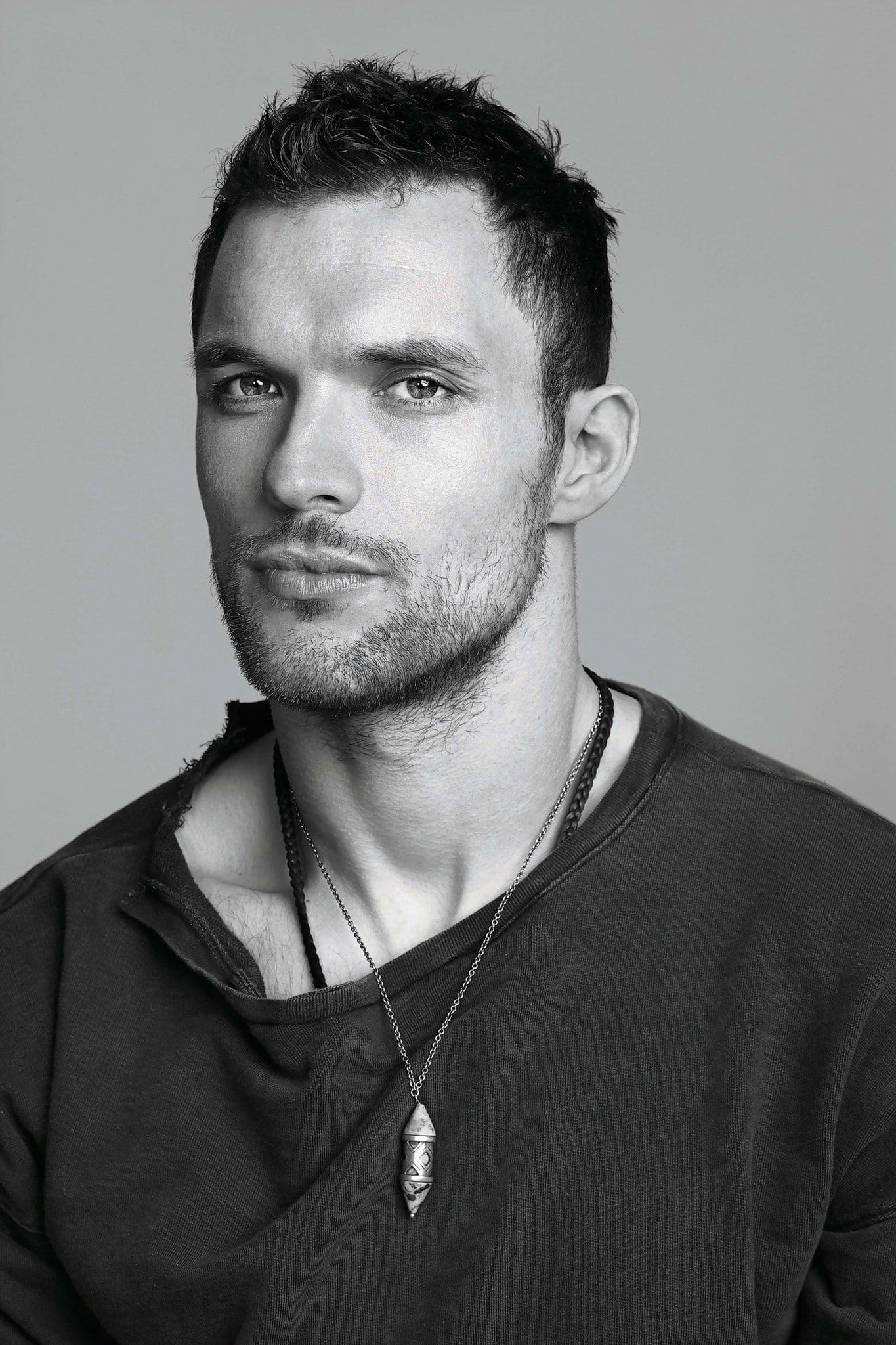

ed

skrein

gives his best to the worst

Written by Erik Rasmussen

Photography by Randall Mesdon

Styled by Paul Sinclaire

Customized sweater UNIQLO Necklace PAMELA LOVE Leather necklace FEATHERED SOUL

Five minutes into our conversation Ed Skrein has me crying. We’re sitting at a table after his photo shoot with At Large. Coffee is coming. He’s boarding a flight bound for LA in a couple hours for pressers before the release of his latest film, Deadpool, crushes it in theaters nationwide. But he’s telling me about his work on another production, shot in Morocco, a little HBO show called Game of Thrones. Which, by his telling, was a beautiful experience, though the cast was so big it was the least intimate he’s ever felt on set. It was his connection to the crew there, the set designers, production staff, and especially to the costume department, which he describes with touching praise, that’s caused droplets to form around my eyes. “The lady who did the clothes was a beautiful person. The costumes were very considered, and the attention to detail was stunning. They did an incredible job. Everyone had diarrhea, man.” Cue belly laughs. Why are the shits always funny, I wonder aloud. “Especially when the intricacies of the costume’s construction make it hard to take off in time,” notes Skrien. “I couldn’t shit myself cos’ the poor wardrobe assistant would see it everywhere.” Spell complete. I fall into a laughing fit of tears. Jokes aside, the account turns out to be a clear and, er, visceral analog of Skrein’s personality, that of a smart and wickedly entertaining bloke with an ability to blend moments of real tenderness into the frank and ribald.

Skrein is tall, his body built through years of competitive swimming. His appearance is easy to describe, handsome, but his looks are more complicated, even emotional: depending on the angle, the planes of his face morph from poetic into something more dangerous. The effect is similar to Markus Raetz’s sculpture Yes–No, and I imagine that had something to do with Deadpool’s director, Rhett Reese, casting him as the villain Ajax in the blockbuster Marvel movie. Now, sipping his black coffee in his black jeans, black T-shirt, and black leather jacket, Skrein could be a denizen of Hubert Selby Jr.’s Brooklyn, or perhaps a thief imagined by Jean Genet.

In the age of Wikipedia and TMZ, there’s no hot news to break on Ed Skrein. He was raised in Islington, a middle-class borough of London, graduated from Central Saint Martins with a degree in fine arts, recorded some hip-hop music, and now, at age thirty-three, is one of the hottest tickets in Hollywood. What I offer is context. How does a man with an art degree and a microphone manage to imbue such depth and complexity into an acting role without having any previous training in drama? Let’s start not with his schooling but his education—not where he matured but how he formed—and with no better words than his own:

“Early on, I became fascinated and obsessed with Jean-Michel Basquiat. I was introduced to his work by my incredible art teacher, Ms. Snowsill, when I was fifteen. Then my aunty bought me some of his books and that’s where the love affair started. I saw Julian Schnabel’s film Basquiat and it just blew my mind. It really fit with the style of music I was getting into at the time: I’d just discovered Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). Those influences came together and it was like, Damn, this resonates, I don’t know why, but it just feels right. In school at the time, there weren’t many people who liked hip-hop*. There was the junglist movement. And then there was garage music, which was great, and we used to party to it. But I loved hip-hop. I carried a backpack in school and I’d only have a Walkman and cassette tapes in it. I wouldn’t have a pen, or any fucking books. Just cassettes that I’d taped off the radio: Tim Westwood, Funkmaster Flex, Cipha Sounds, the Big Dawg Pitbulls. That was the golden era, man. Another one of my teachers, Mr. Jones, gave me Snoop Dogg and Naughty by Nature tapes. Now you could be sacked for giving kids that shit. But the thing is, when we heard it, it was just cool as fuck. We didn’t even understand what “O.P.P.” was [Other People’s Pussy/Penis, for those still unfamiliar with nineties hip-hop classics]. What Mr. Jones did was feed culture to certain kids who he could see it would resonate with. He drove a fucked-up car that would backfire and make loads of noise, and he smoked cigarettes, wore leather jackets, and had orange teeth. He was so inspiring. Then my sister gave me Gang Starr’s album Hard to Earn and that was it, that was like finding Keith Haring and Basquiat again. I’d get together with five friends from school and we’d rap Guru and or The Pharcyde lyrics, and [singing] “M–E–T–H–O–D man.” That was the beginning of it. It was the feeling of like, I don’t know what this is, but it feels right and I’m gonna explore it. We became this street entrepreneurial thing, like Fight Club. We’d walk around London with our headphones on and our trousers hanging down our asses, go to one of our mums’ basements and record cypher mixtapes for hours. Then we went on to getting stage shows together, and stepping it up. But it got to the point where it was romantically corrupted, where I started to hang onto it a bit too much. That was the only time in my life where, I suppose, I really wanted something, really needed something. And I don’t think that’s healthy. I see it now with some other actors, they want something so bad. And it doesn’t help. That’s why in this game now—I’ve become the opposite of that. I love acting, I feel this is where I’m supposed to be, this is what I’m supposed to be doing, but by the same token I don’t need this. I’ve made some stuff that I’m proud of, and I’ve created some breathing room financially. What I can do now is really find those projects that resonate, and I can stay romantic and try to keep it sacred. Don’t make it desperate, y’know? Keep it pure.”

Skrein, who went on to have a successful underground hip-hop career, recording under the Dented Records label and collaborating with notable acts Foreign Beggars, Asian Dub Foundation, and others (again, Wikipedia, have at it), sees no boundaries between rap, swimming, or acting. It’s all performance, it’s craftwork, art. “Even my painting was performance based,” he says, describing big swimmerly brushstrokes and pitching paint against the canvas. There’s a long tempting line of recording artist precedents, but it’s rappers who have lately proven adept at transitioning to motion pictures. This makes apparent sense from a performance perspective, plus rappers come predisposed to character acting, which I can demonstrate by pointing to their alter egos: O’Shea “Ice Cube” Jackson, Dana “Queen Latifah” Owens, Dante “Mos Def” Smith, Mark “Marky Mark” Wahlberg, and Will “Fresh Prince” Smith, not to mention a diamond-edged confidence that comes with the hard-won hip-hop territory. For Skrein’s part, he says he had no interest in acting in his hip-hop heyday, nor does he see a linear progression from stages and PAs to back lots and boom mics. There was no obvious segue. “I’ve always known when I saw something I liked and known when it’s right,” he says. With the kind of numbers Deadpool has posted since its unlikely February release (who drops a superhero movie midwinter?), he’s feeling all right indeed.

Yet his first film nearly went all wrong. A mere five years ago, when Skrein was twenty-seven years old, his friend Ben Drew asked him to costar in a film Drew would direct. Skrein would play Ed, a sociopathic drug dealer who pimps out a heroin addict. The character, though not based on Skrein in any literal sense, was written for him. Drew, himself a hip-hop artist known as Plan B, had collaborated on records with Skrein. Well aware of the meticulous and competitive preparation Skrein brought to rap performances**, Drew bet he’d give his best to the worst. “I properly went into the script,” Skrein recalls. “I lived that shit. I researched it—in-depth!—and went a bit overboard.” Halfway through filming, Skrein had a realization. “I couldn’t relate to a despicable person like that. The character disturbed me on a psychological level. I thought, Acting isn’t for me.”

Few would agree. Since stumbling off the starting block, Skrein’s star has quickly ascended, including refueling the lead role in The Transporter, which was recently vacated by Jason Statham, and winning an MTV Movie Award for Best Fight along with his Deadpool costar, Ryan Reynolds. Skrein has settled in, and found his stroke.

“When I’m on set, everything is good,” he says about his acting experiences now. “I’m in the creative process, performing, I’m happy. On the set of Deadpool, Rhett would say to me, ‘If this were the Titanic you’d be one of the guys playing music on the way down.’” They have a phrase for this, Reese and his girlfriend, for tireless optimism in the shadow of work-related fatigue and annoyance: Skrein up! It means stop complaining.

Customized sweater UNIQLO Necklace PAMELA LOVE Leather necklace FEATHERED SOUL

To be clear, Skrein does not consider acting a tough job. “The hard part is being away from my family,” he says. And the sixteen-hour days? “It’s just bags under your eyes. No, it’s not a tough job, but it can be hard work if you work hard at it.” His ethic involves an obsessive study of the script, mentally preparing himself. “It always goes back to the text,” he says. “I have to be Frank Sinatra, not Bob Dylan”—meaning he’s not the person who writes the stuff, he’s the performer, the guy who sings “My Way” and makes the audience believe it’s the story of his life. “I’ve heard that Anthony Hopkins reads a script two hundred and fifty times. I try to read the script as much as possible. After that, I do conceptual stuff.” And what emotional influences did Skrein conceive for the bloodletter of Deadpool, what psychological touchstones did he build into his inner bad man? “As the character,” he explains, “I need to know what my mother’s front door looks like. I’ll choose an album for him. For Ajax it was Gregory Porter’s Liquid Spirit. I’ll find other characters that fit close to my idea of him. For Ajax it was Roy Batty in Blade Runner, and Chigurh in No Country for Old Men. It was Joseph Goebbels. It was Harold Shipman, the doctor who murdered two hundred patients and could still speak calmly to the press. The calm makes the villain,” he says serenely, and I imagine him arriving to set on the first shoot day, collected, cool, his angles and planes aligned with his inner freak, switching yes to no. “I arrive to set the first day and feel like nothing has prepared me,” Skrein corrects me. “I’m not a nervous person,” he continues, “but I do get this beautiful anxiety. And just before the first take, when the lights are on and the cameras are rolling, I take a deep breath and go, Fuck it.”

That’s a performer, competitive in the act—a quick wit sharpened in cypher mind games, an athlete primed by extra effort. That’s Ed Skrein on set, standing as if on the precipice of something, hands atremble, heart on fire, feeling it resonate.

————————

*It might be useful to make a distinction here between rap and hip-hop. KRS One made this clarification: rap is something you do, hip-hop is something you live.

** “Anyone who knew me back in the cypher days knew I was an animal,” Skrein says of his method. “Nothing is more improvisational than a cypher, and nothing is more competitive. We all need each other. We hope the other person will do better. But there’s also a sense that when he does better, I’m going to do better than him.”

Special thanks to Clare Fentress