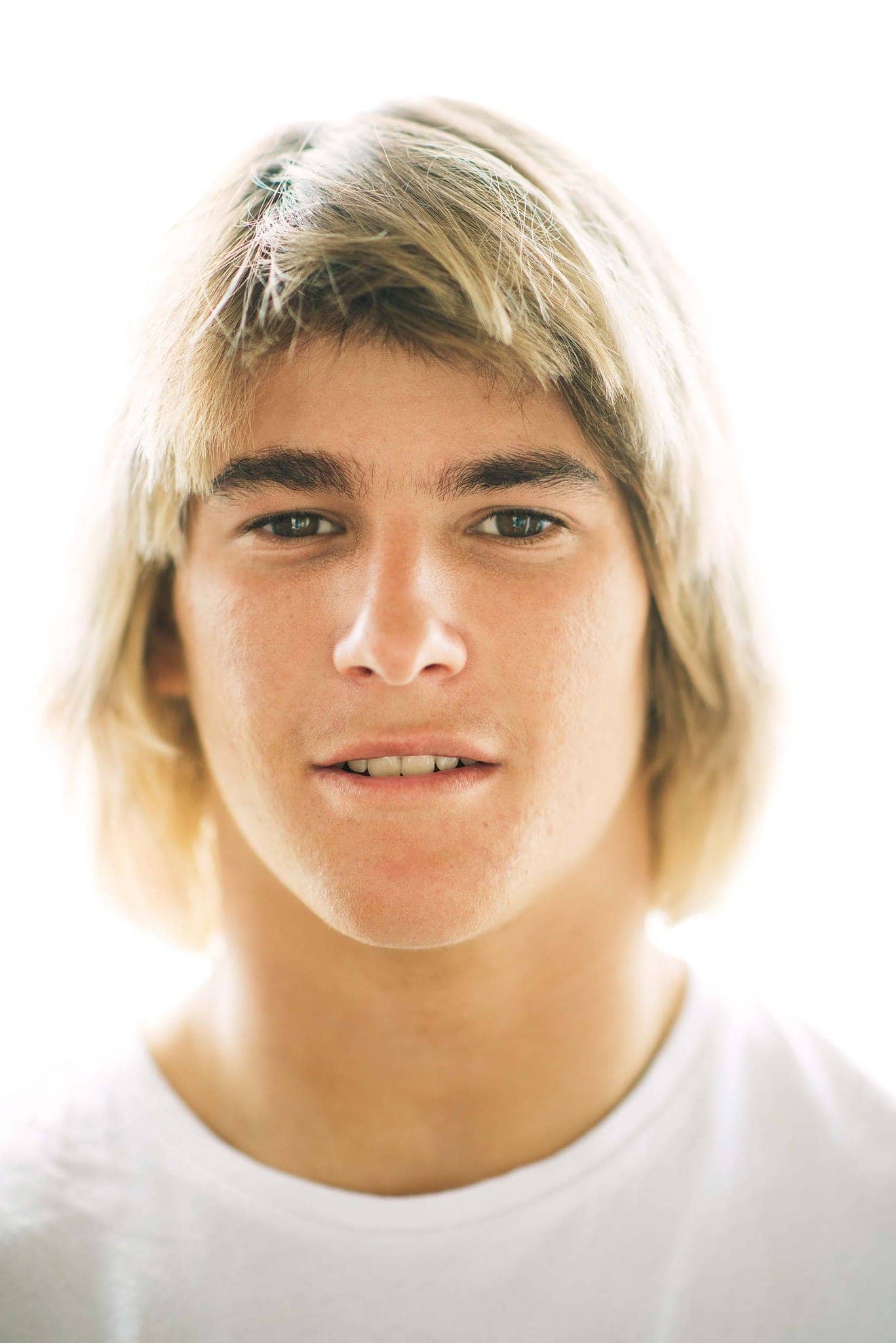

the arrival of

jack robinson

surfing’s new prodigy

Written by Whitman Bedwell

Photography by Justin Jay

After watching then fourteen-year-old Jack Robinson emerge victorious over older competition in a Western Australia surf contest, Taj Burrow said, “I think he’d have to be the best in the world for his age.” It was a powerful claim from a man considered one of the best surfers of his own generation, and it gave authority to what many already knew about Jack’s abilities. It was the truth, because Jack Robinson can do things in the ocean and on a surfboard that everyone else his age cannot. He is a once-in-a-generation talent. Jack Robinson is a surfing prodigy.

Now, at seventeen years old, Robinson will soon no longer be a prodigy. He will be a man, and his ability to ride waves at the highest level won’t be defined by his age. Gone will be the benefit of having his talent and accomplishments rest on the expectations of what a teenager can do on a surfboard. His surfing will be defined as it is, without qualifiers, and it will be judged against the standard set by every great surfer that has come before him.

It’s a frightening thing to be a prodigy, and even more frightening to lose prodigal status. Such talent at a young age leads to hype, and hype often leads to impossible expectations. Few surfing prodigies have met, let alone exceeded, the expectations hanging over Robinson’s head. For every Kelly Slater and John John Florence who delivered on the expectation that they’d one day be the best, countless others burned out before their potential was reached.

The “lost prodigy” is found in all sports, but it is especially common in surfing. What makes surfing so different from other sports is that the “field”—the waves and the ocean—are players too, and the way a child, even a very gifted one, rides waves is different than how an adult does. Adulthood means new adult bodies and new adult strength, and it requires adjustments in approach that some prodigies cannot grow into.

Despite the process of maturation, or maybe because of it, Jack Robinson will succeed. Robinson never surfed like a boy, but rather with the ability of a man. The unnatural movements and style of a child do not plague him. Robinson is calm and confident on a surfboard. He uses the wave against itself, and draws from its speed and power to allow him to do as he wishes on it. Most impressive of all is his composure on waves of consequence: heavy, powerful waves where a boy should not be comfortable and fearless, yet where Jack has, in the rough ocean off the Western Australia coast, learned to be just that. It’s this distinction in Robinson’s surfing that makes so many surfers willing to project his greatness. It’s why Taj Burrow, whose words carry so much weight, is willing to bestow such high expectations upon Robinson. Consider it a warning: Jack Robinson is coming, and he will arrive fully grown, and with the tools of his ability growing sharper.

This past winter, on the North Shore of Oahu, Robinson won the Pipe Masters trials and received an invitation to its main event. The Pipe Masters is the most important surf contest in the world, and it is held at the world’s most famous and dangerous wave, the Banzai Pipeline. His victory over the inveterate Hawaiian locals that day should put to rest any idea of Robinson as merely a great young surfer. The grown men who lost to him do not see him as such. And, if he continues like he has, he won’t give anyone a choice.